Modern Monetary Theory, an unconventional take on economic strategy

By Dylan Matthews

February 18 (Bloomberg) — About 11 years ago, James K. “Jamie” Galbraith recalls, hundreds of his fellow economists laughed at him. To his face. In the White House.

It was April 2000, and Galbraith had been invited by President Bill Clinton to speak on a panel about the budget surplus. Galbraith was a logical choice. A public policy professor at the University of Texas and former head economist for the Joint Economic Committee, he wrote frequently for the press and testified before Congress.

What’s more, his father, John Kenneth Galbraith, was the most famous economist of his generation: a Harvard professor, best-selling author and confidante of the Kennedy family. Jamie has embraced a role as protector and promoter of the elder’s legacy.

But if Galbraith stood out on the panel, it was because of his offbeat message. Most viewed the budget surplus as opportune: a chance to pay down the national debt, cut taxes, shore up entitlements or pursue new spending programs.

He viewed it as a danger: If the government is running a surplus, money is accruing in government coffers rather than in the hands of ordinary people and companies, where it might be spent and help the economy.

“I said economists used to understand that the running of a surplus was fiscal (economic) drag,” he said, “and with 250 economists, they giggled.”

Galbraith says the 2001 recession — which followed a few years of surpluses — proves he was right.

A decade later, as the soaring federal budget deficit has sharpened political and economic differences in Washington, Galbraith is mostly concerned about the dangers of keeping it too small. He’s a key figure in a core debate among economists about whether deficits are important and in what way. The issue has divided the nation’s best-known economists and inspired pockets of passion in academic circles. Any embrace by policymakers of one view or the other could affect everything from employment to the price of goods to the tax code.

In contrast to “deficit hawks” who want spending cuts and revenue increases now in order to temper the deficit, and “deficit doves” who want to hold off on austerity measures until the economy has recovered, Galbraith is a deficit owl. Owls certainly don’t think we need to balance the budget soon. Indeed, they don’t concede we need to balance it at all. Owls see government spending that leads to deficits as integral to economic growth, even in good times.

The term isn’t Galbraith’s. It was coined by Stephanie Kelton, a professor at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, who with Galbraith is part of a small group of economists who have concluded that everyone — members of Congress, think tank denizens, the entire mainstream of the economics profession — has misunderstood how the government interacts with the economy. If their theory — dubbed “Modern Monetary Theory” or MMT — is right, then everything we thought we knew about the budget, taxes and the Federal Reserve is wrong.

Keynesian roots

“Modern Monetary Theory” was coined by Bill Mitchell, an Australian economist and prominent proponent, but its roots are much older. The term is a reference to John Maynard Keynes, the founder of modern macroeconomics. In “A Treatise on Money,” Keynes asserted that “all modern States” have had the ability to decide what is money and what is not for at least 4,000 years.

This claim, that money is a “creature of the state,” is central to the theory. In a “fiat money” system like the one in place in the United States, all money is ultimately created by the government, which prints it and puts it into circulation. Consequently, the thinking goes, the government can never run out of money. It can always make more.

This doesn’t mean that taxes are unnecessary. Taxes, in fact, are key to making the whole system work. The need to pay taxes compels people to use the currency printed by the government. Taxes are also sometimes necessary to prevent the economy from overheating. If consumer demand outpaces the supply of available goods, prices will jump, resulting in inflation (where prices rise even as buying power falls). In this case, taxes can tamp down spending and keep prices low.

But if the theory is correct, there is no reason the amount of money the government takes in needs to match up with the amount it spends. Indeed, its followers call for massive tax cuts and deficit spending during recessions.

Warren Mosler, a hedge fund manager who lives in Saint Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands — in part because of the tax benefits — is one proponent. He’s perhaps better know for his sports car company and his frequent gadfly political campaigns (he earned a little less than one percent of the vote as an independent in Connecticut’s 2010 Senate race). He supports suspending the payroll tax that finances the Social Security trust fund and providing an $8 an hour government job to anyone who wants one to combat the current downturn.

The theory’s followers come mainly from a couple of institutions: the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s economics department and the Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, both of which have received money from Mosler. But the movement is gaining followers quickly, largely through an explosion of economics blogs. Naked Capitalism, an irreverent and passionately written blog on finance and economics with nearly a million monthly readers, features proponents such as Kelton, fellow Missouri professor L. Randall Wray and Wartberg College professor Scott Fullwiler. So does New Deal 2.0, a wonky economics blog based at the liberal Roosevelt Institute think tank.

Their followers have taken to the theory with great enthusiasm and pile into the comment sections of mainstream economics bloggers when they take on the theory. Wray’s work has been picked up by Firedoglake, a major liberal blog, and the New York Times op-ed page. “The crisis helped, but the thing that did it was the blogosphere,” Wray says. “Because, for one thing, we could get it published. It’s very hard to publish anything that sounds outside the mainstream in the journals.”

Most notably, Galbraith has spread the message everywhere from the Daily Beast to Congress. He advised lawmakers including then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) when the financial crisis hit in 2008. Last summer he consulted with a group of House members on the debt ceiling negotiations. He was one of the handful of economists consulted by the Obama administration as it was designing the stimulus package. “I think Jamie has the most to lose by taking this position,” Kelton says. “It was, I think, a really brave thing to do, because he has such a big name, and he’s so well-respected.”

Wray and others say they, too, have consulted with policymakers, and there is a definite sense among the group that the theory’s time is now. “Our Web presence, every few months or so it goes up another notch,” Fullwiler says.

A divisive theory

The idea that deficit spending can help to bring an economy out of recession is an old one. It was a key point in Keynes’s “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.” It was the chief rationale for the 2009 stimulus package, and many self-identified Keynesians, such as former White House adviser Christina Romer and economist Paul Krugman, have argued that more is in order. There are, of course, detractors.

A key split among Keynesians dates to the 1930s. One set of economists, including the Nobel laureates John Hicks and Paul Samuelson, sought to incorporate Keynes’s insights into classical economics. Hicks built a mathematical model summarizing Keynes’s theory, and Samuelson sought to wed Keynesian macroeconomics (which studies the behavior of the economy as a whole) to conventional microeconomics (which looks at how people and businesses allocate resources). This set the stage for most macroeconomic theory since. Even today, “New Keynesians,” such as Greg Mankiw, a Harvard economist who served as chief economic adviser to George W. Bush, and Romer’s husband, David, are seeking ways to ground Keynesian macroeconomic theory in the micro-level behavior of businesses and consumers.

Modern Monetary theorists hold fast to the tradition established by “post-Keynesians” such as Joan Robinson, Nicholas Kaldor and Hyman Minsky, who insisted Samuelson’s theory failed because its models acted as if, in Galbraith’s words, “the banking sector doesn’t exist.”

The connections are personal as well. Wray’s doctoral dissertation was advised by Minsky, and Galbraith studied with Robinson and Kaldor at the University of Cambridge. He argues that the theory is part of an “alternative tradition, which runs through Keynes and my father and Minsky.”

And while Modern Monetary Theory’s proponents take Keynes as their starting point and advocate aggressive deficit spending during recessions, they’re not that type of Keynesians. Even mainstream economists who argue for more deficit spending are reluctant to accept the central tenets of Modern Monetary Theory. Take Krugman, who regularly engages economists across the spectrum in spirited debate. He has argued that pursuing large budget deficits during boom times can lead to hyperinflation. Mankiw concedes the theory’s point that the government can never run out of money but doesn’t think this means what its proponents think it does.

Technically it’s true, he says, that the government could print streams of money and never default. The risk is that it could trigger a very high rate of inflation. This would “bankrupt much of the banking system,” he says. “Default, painful as it would be, might be a better option.”

Mankiw’s critique goes to the heart of the debate about Modern Monetary Theory —?and about how, when and even whether to eliminate our current deficits.

When the government deficit spends, it issues bonds to be bought on the open market. If its debt load grows too large, mainstream economists say, bond purchasers will demand higher interest rates, and the government will have to pay more in interest payments, which in turn adds to the debt load.

To get out of this cycle, the Fed?— which manages the nation’s money supply and credit and sits at the center of its financial system — could buy the bonds at lower rates, bypassing the private market. The Fed is prohibited from buying bonds directly from the Treasury — a legal rather than economic constraint. But the Fed would buy the bonds with money it prints, which means the money supply would increase. With it, inflation would rise, and so would the prospects of hyperinflation.

“You can’t just fund any level of government that you want from spending money, because you’ll get runaway inflation and eventually the rate of inflation will increase faster than the rate that you’re extracting resources from the economy,” says Karl Smith, an economist at the University of North Carolina. “This is the classic hyperinflation problem that happened in Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic.”

The risk of inflation keeps most mainstream economists and policymakers on the same page about deficits: In the medium term — all else being equal — it’s critical to keep them small.

Economists in the Modern Monetary camp concede that deficits can sometimes lead to inflation. But they argue that this can only happen when the economy is at full employment — when all who are able and willing to work are employed and no resources (labor, capital, etc.) are idle. No modern example of this problem comes to mind, Galbraith says.

“The last time we had what could be plausibly called a demand-driven, serious inflation problem was probably World War I,” Galbraith says. “It’s been a long time since this hypothetical possibility has actually been observed, and it was observed only under conditions that will never be repeated.”

Critics’ rebuttals

According to Galbraith and the others, monetary policy as currently conducted by the Fed does not work. The Fed generally uses one of two levers to increase growth and employment. It can lower short-term interest rates by buying up short-term government bonds on the open market. If short-term rates are near-zero, as they are now, the Fed can try “quantitative easing,” or large-scale purchases of assets (such as bonds) from the private sector including longer-term Treasuries using money the Fed creates. This is what the Fed did in 2008 and 2010, in an emergency effort to boost the economy.

According to Modern Monetary Theory, the Fed buying up Treasuries is just, in Galbraith’s words, a “bookkeeping operation” that does not add income to American households and thus cannot be inflationary.

“It seemed clear to me that .?.?. flooding the economy with money by buying up government bonds .?.?. is not going to change anybody’s behavior,” Galbraith says. “They would just end up with cash reserves which would sit idle in the banking system, and that is exactly what in fact happened.”

The theorists just “have no idea how quantitative easing works,” says Joe Gagnon, an economist at the Peterson Institute who managed the Fed’s first round of quantitative easing in 2008. Even if the money the Fed uses to buy bonds stays in bank reserves — or money that’s held in reserve — increasing those reserves should still lead to increased borrowing and ripple throughout the system.

Mainstreamers are equally baffled by another claim of the theory: that budget surpluses in and of themselves are bad for the economy. According to Modern Monetary Theory, when the government runs a surplus, it is a net saver, which means that the private sector is a net debtor. The government is, in effect, “taking money from private pockets and forcing them to make that up by going deeper into debt,” Galbraith says, reiterating his White House comments.

The mainstream crowd finds this argument as funny now as they did when Galbraith presented it to Clinton. “I have two words to answer that: Australia and Canada,” Gagnon says. “If Jamie Galbraith would look them up, he would see immediate proof he’s wrong. Australia has had a long-running budget surplus now, they actually have no national debt whatsoever, they’re the fastest-growing, healthiest economy in the world.” Canada, similarly, has run consistent surpluses while achieving high growth.

To even care about such questions, Galbraith says, marked him as “a considerable eccentric” when he arrived from Cambridge to get a PhD at Yale, which had a more conventionally Keynesian economics department. Galbraith credits Samuelson and his allies’ success to a “mass-marketing of economic doctrine, of which Samuelson was the great master .?.?. which is something the Cambridge school could never have done.”

The mainstream economists are loath to give up any ground, even in cases such as the so-called “Cambridge capital controversy” of the 1960s. Samuelson debated post-Keynesians and, by his own admission, lost. Such matters have been, in Galbraith’s words, “airbrushed, like Trotsky” from the history of economics.

But MMT’s own relationship to real-world cases can be a little hit-or-miss. Mosler, the hedge fund manager, credits his role in the movement to an epiphany in the early 1990s, when markets grew concerned that Italy was about to default. Mosler figured that Italy, which at that time still issued its own currency, the lira, could not default as long as it had the ability to print more liras. He bet accordingly, and when Italy did not default, he made a tidy sum. “There was an enormous amount of money to be made if you could bring yourself around to the idea that they couldn’t default,” he says.

Later that decade, he learned there was also a lot of money to be lost. When similar fears surfaced about Russia, he again bet against default. Despite having its own currency, Russia defaulted, forcing Mosler to liquidate one of his funds and wiping out much of his $850 million in investments in the country. Mosler credits this to Russia’s fixed exchange rate policy of the time and insists that if it had only acted like a country with its own currency, default could have been avoided.

But the case could also prove what critics insist: Default, while technically always avoidable, is sometimes the best available option.

Category Archives: Canada

Canada Employment

But their banking system is sound.

Like talking about how good the person looked at his funeral?

Karim writes:

Another downbeat number with the unemployment rate rising to an 8mth high of 7.6% (from 7.5%).

Total employment up 2.3k, with full-time jobs -3.6k after -21.7k the prior month.

In the past 5mths the unemployment rate in Canada has risen by 0.4% while the U.S. has fallen 0.6% (subject to today’s #)-a large move in a short time.

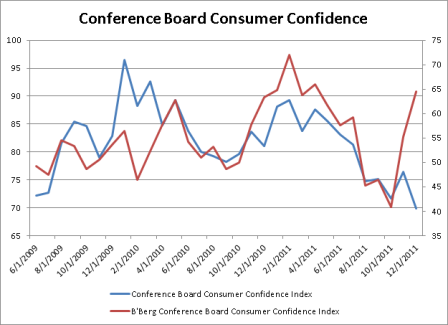

Chart below shows the recent divergence in Conference Board confidence surveys for Canada (blue) and U.S. (red).

John Carney on MMT and Austrian Economics

Another well stated piece from John Carney on the CNBC website:

Modern Monetary Theory and Austrian Economics

By John Carney

Dec 27 (CNBC) — When I began blogging about Modern Monetary Theory, I knew I risked alienating or at least annoying some of my Austrian Economics friends. The Austrians are a combative lot, used to fighting on the fringes of economic thought for what they see as their overlooked and important insights into the workings of the economy.

Which is one of the things that makes them a lot like the MMT crowd.

There are many other things that Austrian Econ and MMT share. A recent post by Bob Wenzel at Economic Policy Journal, which is presented as a critique of my praise of some aspects of MMT, actually makes this point very well.

The MMTers believe that the modern monetary system—sovereign fiat money, unlinked to any commodity and unpegged to any other currency—that exists in the United States, Canada, Japan, the UK and Australia allows governments to operate without revenue constraints. They can never run out of money because they create the money they spend.

This is not to say that MMTers believe that governments can spend without limit. Governments can overspend in the MMT paradigm and this overspending leads to inflation. Government financial assets may be unlimited but real assets available for purchase—that is, goods and services the economy is capable of producing—are limited. The government can overspend by (a) taking too many goods and services out of the private sector, depriving the private sector of what it needs to satisfy the people, grow the economy and increase productivity or (b) increasing the supply of money in the economy so large that it drives up the prices of goods and services.

As Wenzel points out, Murray Rothbard—one of the most important Austrian Economists the United States has produced—takes exactly the same position. He says that governments take “control of the money supply” when they find that taxation doesn’t produce enough revenue to cover expenditures. In other words, fiat money is how governments escape revenue constraint.

Rothbard considers this counterfeiting, which is a moral judgment that depends on the prior conclusion that fiat money isn’t the moral equivalent of real money. Rothbard is entitled to this view—I probably even share it—but that doesn’t change the fact that in our economy today, this “counterfeiting” is the operational truth of our monetary system. We can decry it—but we might as well also try to understand what it means for us.

Rothbard worries that government control of the money supply will lead to “runaway inflation.” The MMTers tend to be more sanguine about the danger of inflation than Rothbard—although I do not believe they are entitled to this attitude. As I explained in my piece “Monetary Theory, Crony Capitalism and the Tea Party,” the MMTers tend to underestimate the influence of special interests—including government actors and central bankers themselves—on monetary policy. They have monetary policy prescriptions that would avoid runaway inflation but, it seems to me, there is little reason to expect these would ever be followed in the countries that are sovereign currency issuers. I think that on this point, many MMTers confuse analysis of the world as it is with the world as they would like it to be.

In short, the MMTers agree with Rothbard on the purpose and effect of government control of money: it means the government is no longer revenue constrained. They differ about the likelihood of runaway inflation , which is not a difference of principle but a divergence of political prediction.

This point of agreement sets both Austrians and MMTers outside of mainstream economics in precisely the same way. They appreciate that the modern monetary system is very, very different from older, commodity based monetary systems—in a way that many mainstream economists do not.

In MM, CC & TP, I briefly mentioned a few other positions on the economy MMTers tend to share. Wenzel writes that “there is nothing right about these views.”

I don’t think Wenzel actually agrees with himself here. Let’s run through these one by one.

1. The MMTers think the financial system tends toward crisis. Wenzel writes that the financial system doesn’t tend toward crisis. But a moment later he admits that the actual financial system we have does tend toward crisis. All Austrians believe this, as far as I can tell.

What has happened here is that Wenzel is now the one confusing the world as it is with the world as he wishes it would be. Perhaps under some version of the Austrian-optimum financial system—no central bank, gold coin as money, free banking or no fractional reserve banking—we wouldn’t tend toward crisis. But that is not the system we have.

The MMTers aren’t engaged with arguing about the Austrian-optimum financial system. They are engaged in describing the actual financial system we have—which tends toward crisis.

They even agree that the tendency toward crisis is largely caused by the same thing, credit expansions leading to irresponsible lending.

2. The MMTers say that “capitalist economies are not self-regulating.” Again, Wenzel dissents. But if we read “capitalist economies” as “modern economies with central banking and interventionist governments” then the point of disagreement vanishes.

Are we entitled to read “capitalist economies” in this way? I think we are. The MMTers are not, for the most part, attempting to argue with non-existent theoretical economies or describe the epic-era Icelandic political economy. They are dealing with the economy we have, which is usually called “capitalist.” Austrians can argue that this isn’t really capitalism—but this is a terminological quibble. When it comes down to the problem of self-regulation of our so-called capitalist system, the Austrians and MMTers are in agreement.

3. Next up is the MMT view (borrowed from an earlier economic school called “Functional Finance”) that fiscal policy should be judged by its economic effects. Wenzel asks if this means that this “supercedes private property that as long as something is good for the economy, it can be taxed away from the individual?”

Here is a genuine difference between the Austrians—especially those of the Rothbardian stripe—and the MMTers. The MMTers do indeed envision the government using taxes to accomplish what is good for the economy—which, for the most part, means combating inflation. They think that the government may need to use taxation to snuff out inflation at times. Alternatively, the government can also reduce its own spending to extinguish inflation.

Note that we’ve come across a gap between MMTers and Rothbardians that is far smaller than the chasm between either of them and mainstream economics, where taxation of private property and income is regularly seen as justified by the need to fund government operations. MMTers and Austrians both agree that under the current circumstances people in most developed countries are overtaxed.

4. Wenzel actually overlooks the larger gap between Austrians and MMTers, which has to do with the efficacy of government spending. Many MMTers believe that most governments in so-called capitalist economies are not spending enough. Most—if not all—Austrians think that these same government are spending too much.

The Austrian view is based on the idea that government spending tends to distort the economy, in part because—as the MMTers would agree—government spending in our age typically involves monetary expansion. The MMTers, I would argue, have a lot to learn from the Austrians on this point. I think that an MMT effort to more fully engage the Austrians on the topic of the structure of production would be well worth the effort.

5. Wenzel’s challenge to the idea of functional finance is untenable—and not particularly Austrian. He argues that the subjectivity of value means it is impossible for us to tell whether something is “good for the economy.” Humbug. We know that an economy that more fully reflects the aspirations and choices of the individuals it encompasses is better than one that does not. We know that high unemployment is worse than low unemployment. All other things being equal, a more productive economy is superior to a less productive economy, a wealthier economy is better than a more impoverished one.

Wenzel’s position amounts to nihilism. I think he is confusing the theory of subjective value with a deeper relativism. Subjectivism is merely the notion that the value of an economic good—that is, an object or a service—is not inherent to the thing but arises from within the individual’s needs and wants. This does not mean that we cannot say that some economic outcome is better or worse or that certain policy prescription are good for the economy and certain are worse.

It would be odd for any Austrian to adopt the nihilism of Wenzel. It’s pretty rare to ever encounter an Austrian who lacks normative views of the economy. These normative views depend on the view that some things are good for economy and some things are bad. I doubt that Wenzel himself really subscribes to the kind of nihilism he seems to advocate in his post.

Wenzel’s final critique of me is that I over-emphasize cronyism and underplay the deeper problems of centralized power. My reply is three-fold. First, cronyism is a more concrete political problem than centralization; tactically, it makes sense to fight cronyism. Second, cronyism is endemic to centralized government decisions, as the public choice economists have shown. They call it special interest rent-seeking, but that’s egg-head talk from cronyism. Third, I totally agree: centralization is a real problem because the “rationalization” involved necessarily downplays the kinds of unarticulated knowledge that are important to everyday life, prosperity and happiness.

At the level of theory, Austrians and MMTers have a lot in common. Tactically, an alliance makes sense. Intellectually, bringing together the descriptive view of modern monetary systems with Austrian views about the structure of production and limitations of economic planning (as well Rothbardian respect for individual property rights) should be a fruitful project.

So, as I said last time, let’s make it happen.

Comments on Senator Sanders article on the Fed

Dear Senator Sanders,

Thank you for your attention to this matter!

My comments appear below:

The Veil of Secrecy at the Fed Has Been Lifted, Now It’s Time for Change

By Senator Bernie Sanders

November 2 (Huffington Post) — As a result of the greed, recklessness, and illegal behavior on Wall Street, the American people have experienced the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression.

Not to mention the institutional structure that rewarded said behavior, and, more important, the failure of government to respond in a timely manner with policy to ensure the financial crisis didn’t spill over to the real economy.

Millions of Americans, through no fault of their own, have lost their jobs, homes, life savings, and ability to send their kids to college. Small businesses have been unable to get the credit they need to expand their businesses, and credit is still extremely tight. Wages as a share of national income are now at the lowest level since the Great Depression, and the number of Americans living in poverty is at an all-time high.

Yes, it’s all a sad disgrace.

Meanwhile, when small-business owners were being turned down for loans at private banks and millions of Americans were being kicked out of their homes, the Federal Reserve provided the largest taxpayer-financed bailout in the history of the world to Wall Street and too-big-to-fail institutions, with virtually no strings attached.

Only partially true. For the most part the institutions did fail, as shareholder equity was largely lost. Failure means investors lose, and the assets of the failed institution sold or otherwise transferred to others.

But yes, some shareholders and bonds holders (and executives) who should have lost were protected.

Over two years ago, I asked Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, a few simple questions that I thought the American people had a right to know: Who got money through the Fed bailout? How much did they receive? What were the terms of this assistance?

Incredibly, the chairman of the Fed refused to answer these fundamental questions about how trillions of taxpayer dollars were being spent.

The American people are finally getting answers to these questions thanks to an amendment I included in the Dodd-Frank financial reform bill which required the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to audit and investigate conflicts of interest at the Fed. Those answers raise grave questions about the Federal Reserve and how it operates — and whose interests it serves.

As a result of these GAO reports, we learned that the Federal Reserve provided a jaw-dropping $16 trillion in total financial assistance to every major financial institution in the country as well as a number of corporations, wealthy individuals and central banks throughout the world.

Yes, however, while I haven’t seen the detail, that figure likely includes liquidity provision to FDIC insured banks which is an entirely separate matter and not rightly a ‘bailout’.

The US banking system (rightly) works to serve public purpose by insuring deposits and bank liquidity in general. And history continues to ‘prove’ banking in general can work no other way.

And once government has secured the banking system’s ability to fund itself, regulation and supervision is then applied to ensure banks are solvent as defined by the regulations put in place by Congress, and that all of their activities are in compliance with Congressional direction as well.

The regulators are further responsible to appropriately discipline banks that fail to comply with Congressional standards.

Therefore, the issue here is not with the liquidity provision by the Fed, but with the regulators and supervisors who oversee what the banks do with their insured, tax payer supported funding.

In other words, the liability side of banking is not the place for market discipline. Discipline comes from regulation and supervision of bank assets, capital, and management.

The GAO also revealed that many of the people who serve as directors of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks come from the exact same financial institutions that the Fed is in charge of regulating. Further, the GAO found that at least 18 current and former Fed board members were affiliated with banks and companies that received emergency loans from the Federal Reserve during the financial crisis. In other words, the people “regulating” the banks were the exact same people who were being “regulated.” Talk about the fox guarding the hen house!

Yes, this is a serious matter. On the one hand you want directors with direct banking experience, while on the other you strive to avoid conflicts of interest.

The emergency response from the Fed appears to have created two systems of government in America: one for Wall Street, and another for everyone else. While the rich and powerful were “too big to fail” and were given an endless supply of cheap credit, ordinary Americans, by the tens of millions, were allowed to fail.

The Fed necessarily sets the cost of funds for the economy through its designated agents, the nations Fed member banks. It was the Fed’s belief that, in general, a lower cost of funds for the banking system, presumably to be passed through to the economy, was in the best interest of ‘ordinary Americans.’ And note that the lower cost of funds from the Fed does not necessarily help bank earnings and profits, as it reduces the interest banks earn on their capital and on excess funds banks have that consumers keep in their checking accounts.

However, there was more that Congress could have done to keep homeowners from failing, beginning with making an appropriate fiscal adjustment in 2008 as the financial crisis intensified, and in passing regulations regarding foreclosure practices.

Additionally, it should also be recognized that the Fed is, functionally, an agent of Congress, subject to immediate Congressional command. That is, the Congress has the power to direct the Fed in real time and is thereby also responsible for failures of Fed policy.

They lost their homes. They lost their jobs. They lost their life savings. And, they lost their hope for the future. This is not what American democracy is supposed to look like. It is time for change at the Fed — real change.

I blame this almost entirely on the failure of Congress to make the immediate and appropriate fiscal adjustments in 2008 that would have sustained employment and output even as the financial crisis took its toll on the shareholder equity of the financial sector.

Congress also failed to act with regard to issues surrounding the foreclosure process that have worked against public purpose.

Among the GAO’s key findings is that the Fed lacks a comprehensive system to deal with conflicts of interest, despite the serious potential for abuse. In fact, according to the GAO, the Fed actually provided conflict of interest waivers to employees and private contractors so they could keep investments in the same financial institutions and corporations that were given emergency loans.

The GAO has detailed instance after instance of top executives of corporations and financial institutions using their influence as Federal Reserve directors to financially benefit their firms, and, in at least one instance, themselves.

For example, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase served on the New York Fed’s board of directors at the same time that his bank received more than $390 billion in financial assistance from the Fed. Moreover, JP Morgan Chase served as one of the clearing banks for the Fed’s emergency lending programs.

This demands thorough investigation, and in any case the conflict of interest should have been publicly revealed at the time.

Getting this type of disclosure was not easy. Wall Street and the Federal Reserve fought it every step of the way. But, as difficult as it was to lift the veil of secrecy at the Fed, it will be even harder to reform the Fed so that it serves the needs of all Americans, and not just Wall Street. But, that is exactly what we have to do.

Yes, I have always supported full transparency.

To get this process started, I have asked some of the leading economists in this country to serve on an advisory committee to provide Congress with legislative options to reform the Federal Reserve.

Here are some of the questions that I have asked this advisory committee to explore:

1. How can we structurally reform the Fed to make our nation’s central bank a more democratic institution responsive to the needs of ordinary Americans, end conflicts of interest, and increase transparency? What are the best practices that central banks in other countries have developed that we can learn from? Compared with central banks in Europe, Canada, and Australia, the GAO found that the Federal Reserve does not do a good job in disclosing potential conflicts of interest and other essential elements of transparency.

Yes, full transparency in ‘real time’ would serve public purpose.

2. At a time when 16.5 percent of our people are unemployed or under-employed, how can we strengthen the Federal Reserve’s full-employment mandate and ensure that the Fed conducts monetary policy to achieve maximum employment? When Wall Street was on the verge of collapse, the Federal Reserve acted with a fierce sense of urgency to save the financial system. We need the Fed to act with the same boldness to combat the unemployment crisis.

Unfortunately employment and output is not a function of what’s called ‘monetary policy’ so what is needed from the Fed is full support of an active fiscal policy focused on employment and price stability.

3. The Federal Reserve has a responsibility to ensure the safety and soundness of financial institutions and to contain systemic risks in financial markets. Given that the top six financial institutions in the country now have assets equivalent to 65 percent of our GDP, more than $9 trillion, is there any reason why this extraordinary concentration of ownership should not be broken up? Should a bank that is “too big to fail” be allowed to exist?

Larger size should be permitted only to the extent that it results in lower fees for the consumer. The regulators can require institutions that wish to grow be allowed to do so only in return for lower banking fees.

4. The Federal Reserve has the responsibility to protect the credit rights of consumers. At a time when credit card issuers are charging millions of Americans interest rates between 25 percent or more, should policy options be established to ensure that the Federal Reserve and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau protect consumers against predatory lending, usury, and exorbitant fees in the financial services industry?

Banks are public/private partnerships chartered by government for the further purpose of supporting a financial infrastructure that serves public purpose.

The banks are government agents and should be addressed accordingly, always keeping in mind the mission is to support public purpose.

In this case, because banks are government agents, the question is that of public purpose served by credit cards and related fees, and not the general ‘right’ of shareholders to make profits.

Once public purpose has been established, the effective use of private capital to price risk in the context of a profit motive should then be addressed.

5. At a time when the dream of homeownership has turned into the nightmare of foreclosure for too many Americans, what role should the Federal Reserve be playing in providing relief to homeowners who are underwater on their mortgages, combating the foreclosure crisis, and making housing more affordable?

Again, it begins with a discussion of public purpose, where Congress must decide what, with regard to housing, best serves public purpose. The will of Congress can then be expressed by the institutional structure of its Federal banking system.

Options available, for example, include the option of ordering that appraisals and income statements not be factors in refinancing loans originated by Federal institutions including banks and the Federal housing agencies. At the time of origination the lenders calculated their returns based on mortgages being refinanced as rates came down, assuming all borrowers would be eligible for refinancing. The financial crisis and subsequent failure of policy to sustain employment and output has given lenders an unexpected ‘bonus’ through a ‘technicality’ that allows them to refuse requests for refinancing at lower rates due to lower appraisals and lower incomes.

6. At a time when the United States has the most inequitable distribution of wealth and income of any major country, and the greatest gap between the very rich and everyone else since 1928, what policies can be established at the Federal Reserve which reduces income and wealth inequality in the U.S?

The root causes begin with Federal policy that has resulted in an unprecedented transfer of wealth to the financial sector at the expense of the real sectors. This can easily and immediately be reversed, which would serve to substantially reverse the trend income distribution.

Sincerely,

Warren Mosler

Russia Says Close to Final Stage on China Gas Deal

This is what I’ve proposed the US do with Canada and Mexico- long term contracts for oil and nat gas at ‘fair’ prices would stabilize prices and reduce price disruptions and inflation possibilities of all three economies.

Russia says close to final stage on China gas deal

By Gleb Bryanski

October 11 (Bloomberg) — Russia said on Tuesday it was close to the final stage of a huge gas supply deal with China, in what would be a landmark trade agreement between the long-wary neighbours.

A deal to supply the world’s second biggest economy with up to 68 billion cubic metres of Russian gas a year over 30 years has long been delayed over pricing disagreements.

“We are nearing the final stage of work on gas supplies,” said Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, on his first overseas trip since announcing he was ready to reclaim the Russian presidency.

Putin is hoping his two-day visit will help broaden trade with China, which he expects to grow to $200 billion in 2020 from $59.3 billion last year.

Jobless Claims Dip, Still in Range; Trade Deficit Jumps

As previously discussed, the real economy seems to be muddling through, and at firmer levels than the first half of the year.

The trade report will probably result in Q2 GDP being revised down to just below 1%, but up from the .4% reported for Q1

So Q3 still looks like it will be at least as strong as q2 and likely higher with lower gasoline prices and Japan coming back some.

With corporate profits still looking reasonably strong, corporations continue to demonstrate they can do reasonably well even with low GDP growth and high unemployment.

And with a federal deficit of around 9% of GDP continually adding income, sales, and savings I don’t see a lot of downside to GDP, sales, and profits, though a small negative print is certainly possible.

Jobless Claims Dip, Still in Range; Trade Deficit Jumps

August 11 (Reuters) — New U.S. claims for unemployment benefits dropped to a four-month low last week, government data showed on Thursday, a rare dose of good news for an economy that has been battered by a credit rating downgrade and falling share prices.

Initial claims for state unemployment benefits fell 7,000 to a seasonally adjusted 395,000, the Labor Department said, the lowest level since the week ended April 2.

Economists polled by Reuters had forecast claims steady at 400,000. The prior week’s figure was revised up to 402,000 from the previously reported 400,000.

The Federal Reserve said on Tuesday economic growth was considerably weaker than expected and unemployment would fall only gradually. The U.S. central bank promised to keep interest rates near zero until at least mid-2013.

Hiring accelerated in July after abruptly slowing in the past two months. However, there are worries that a sharp sell-off in stocks and a nasty fight between Democrats and Republicans over raising the government’s debt ceiling could dampen employers’ enthusiasm to hire new workers.

The continued improvement in the labor market could help to allay fears of a new recession, which have been stoked by the economy’s anemic growth pace in the first half of the year.

A Labor Department official said there was nothing unusual in the state-level claims data, adding that only one state had been estimated.

The four-week moving average of claims, considered a better measure of labor market trends, slipped 3,250 to 405,000. Economists say both initial claims and the four-week average need to drop close to 350,000 to signal a sustainable improvement in the labor market.

The number of people still receiving benefits under regular state programs after an initial week of aid dropped 60,000 to 3.69 million in the week ended July 30.

The number of Americans on emergency unemployment benefits fell 26,309 to 3.16 million in the week ended July 23, the latest week for which data is available.

A total of 7.48 million people were claiming unemployment benefits during that period under all programs, down 89,945 from the prior week.

Trade Gap Grows

The US. trade gap widened in June to its largest since October 2008, as both U.S. imports and exports declined in a sign of slowing global demand, a government report showed on Thursday.

The June trade deficit leapt to $53.1 billion, surprising analysts who expected it to narrow to $48 billion from an upwardly revised estimate of $50.8 billion in May.

Overall U.S. imports fell by close to 1 percent, despite a rise in value of crude oil imports to the highest since August 2008. Higher volume pushed the oil import bill higher, as the average price for imported oil fell to $106 per barrel after rising in each of the eight prior months.

U.S. exports fell for a second consecutive month to $170.9 billion, as shipments to Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Central America, France, China and Japan all declined.

Foreigners Make Run on US Housing Market

This is what happens when the Fed scares the heck out of global portfolio managers with otherwise benign QE2, and they deallocate dollar holdings to the point where the currency sells off enough to find real buyers of dollars who want them to buy cheap real assets like US real estate. That’s how ‘price discovery’ finds the real bid side for the dollar for large scale selling.

And when the deallocating stops, this process ends, as that selling pressure fades.

And with the Fed’s portfolio removing maybe $10 billion/month in interest income that otherwise would have gone to the economy, and lower crude prices and a narrowing trade gap in general making $US harder to get overseas, market forces then work to find the offered side of the dollar for that much size.

Foreigners Make Run on US Housing Market

By Diana Olick

June 15 (CNBC) — Falling home prices may be plaguing the US economy, but they are candy to foreign investors, who already have a weak dollar on their side.

Buyers from overseas spent roughly $41 billion on US residential real estate last year, a bump up from the previous year. US real estate agents report a surge this Spring especially, as foreign buyers see continued pressure on home prices and ample bargains.

“I don’t think they’re so concerned about the prices dropping as they are about getting value for their money,” says Rick Ambrose, a Coldwell Banker agent in Lake Mohawk, NJ.

Ambrose and his colleague Mary Pat Spekhardt recently hosted two groups of Japanese investors searching for homes on the scenic lake just about an hour outside of New York City.

“They can work here, be close to the city, be close to their corporations and still feel like they’re on vacation. I think that’s really what grabbed everybody. That’s what got them,” says Spekhardt.

The group of about 35 from Japan also toured properties in Las Vegas and Los Angeles, which are more popular choices among foreign investors.

A new survey by Trulia.com that tracks searches from potential foreign buyers found LA ranked number one in potential interest traffic, trailed by New York City, Cape Coral, Fl, Fort Lauderdale, FL and Las Vegas.

The greatest interest is from buyers in the UK, Canada and Australia.

“Prices now in the US are generally 30-40 percent off from the peak.

In addition, the weakness of the dollar gives the Japanese an advantage, as it does the Europeans, of another 20-25 percent off, so they’re seeing real bargains and opportunities,” notes Ambrose.

The interest is pretty widespread, with Brazilians trolling Miami and Russians and Chinese hunting in Chicago, according to Trulia’s survey.

What’s so interesting to me, though, is that foreigners are so much more ready to jump into the market now than US investors. Granted, they have, as noted, the weak dollar on their side, but they also seem to have a longer term view. US buyers are so afraid to a lose a little in the short term on paper, they don’t realize they could gain a lot in the long term. Of course foreign buyers are largely using cash, which many US buyers are lacking. Credit, or lack thereof, is playing against the US investor.

Prices in Miami are actually beginning to recover, especially in the condo market, thanks to foreign buyers, so much so that the foreigners are beating out the Americans.

I remember all the rage a long time ago when the Japanese were buying up commercial real estate in New York City.

Everyone was so appalled. Not so much now, even up in Lake Mohawk, NJ…

“It isn’t popular. It is unforeseen territory, and it’s unique. I think it’s a very smart choice. It’s not where everyone is looking,” says Spekhardt.

BoC/BoE/RBA Comments

Even with headline ‘inflation’ above comfort levels and recognizing the need to ‘manage inflation expectations’ under ‘expectations theory’ they all religiously believe, they seem to be sufficiently concerned about aggregate demand to make these kinds of dovish comments.

Conclusion: they’re understating the general weakness they’re sensing.

From Karim, my partner at Valance:

Karim writes:

Some important official comments from these 3 in last 24hrs:

Bank of Canada-Still dovish-Highlighting competitiveness issues due to stronger currency, under-representation in emerging markets, and commodity price gains acting as a brake on U.S. growth. No move in policy rate until Q4 at earliest and only to coincide with signal from Fed for higher rates. Excerpts from Carney speech yesterday:

- Since only 10 per cent of Canada’s exports go to emerging economies and our non-commodity export market share in the BRICS has been almost halved over the past decade, activity in Canada does not benefit to the same extent as in past commodity booms driven by U.S. growth. The current situation is more akin to a supply shock for our dominant trading partner, with higher commodity prices acting as a net brake on growth. With oil prices up 50 per cent since last summer, the effect is material.

- Investors looking to rebalance portfolios towards emerging markets could lead them to invest in proxies such as Australia and Canada.

Bank of England-Still dovish-Mervyn King shows no worry from inflation data today (higher than expected but virtually all due to airfares due to timing of late Easter-similar to Eur data) and new MPC Member Broadbent (replacing the uber-hawk Sentence) emphasizing downside risks to growth (higher savings rate, weak credit, Euro stresses). Base case is on hold through year-end.

- King: As set out in my previous letter, the current high level of inflation reflects three main influences: the increase in the standard rate of VAT in January to 20%, higher energy prices and increases in import prices. Although the impact on inflation of these factors is difficult to quantify with precision, it is likely that had they not occurred, inflation would have been substantially lower and probably below the target…..Unemployment is high and wage growth is weak at around 2% a year. Money and credit growth are both very low. It is therefore possible that, as the temporary influence of the factors currently pushing up on inflation wanes, these downward pressures on inflation could drag inflation below the target.

RBA Minutes-Hawkish-Even though 2-speed economy (strong exports/trade; weak consumer), inflation forecast heading higher. Rate hike likely at June or July meeting. The sentence below didn’t appear at the prior RBA meeting in April.

- …members judged that if economic conditions continued to evolve as expected, higher interest rates were likely to be required at some point if inflation was to remain consistent with the medium-term target.

How to exit the euro- a proposal from 1997

This was published in a French newspaper in Quebec in 1997 (in French).

Today it has application in the eurozone, which is briefly discussed as well.

As always, feel free to distribute, repost, etc.

A Plan for Quebec Monetary Independence: The Non-Conformist view of an American Investor

By Warren B. Mosler

Canadian politicians and the media depict the international financial community as being unanimous in its condemnation not only of Quebec political independence but, even more so, of the possibility of a separate Quebec currency. Fearing the uncertainty that such a separate currency would supposedly generate, especially with regard to the international financial community, sovereigntist politicians have always favoured the idea of a monetary union with the rest of Canada and the retention of the Canadian dollar. Indeed, despite the numerous problems that have arisen with the implementation of the Maastricht Treaty in Europe, Quebec sovereigntists have pointed to the EMU as the model to be adopted in the eventuality of Quebec political independence from the rest of Canada. Though not necessarily being favorable to the separation of Quebec because of my lack of understanding of the political issues at stake, being a member of this larger international investment community where millions of US dollars are handled by our firm every day, I believe that such a position on monetary union is misguided. As in Europe, monetary union will essentially entail political union, since ultimately the national fiscal authorities will all have to abide by the bureaucratic decision of the common monetary authority. For this reason, the sovereigntist position is somewhat contradictory on this matter since, by espousing monetary union, Quebec will ultimately guarantee the status quo ante in both monetary and fiscal matters. I have been told that this was at the heart of the major debates between former prime ministers Bourassa and Parizeau some twenty years ago. Why go through the process of separating from the rest of Canada if, on crucial matters pertaining to the economy, all that sovereigntist politicians are apparently offering is something akin to the status quo?

Contrary to the conventional wisdom, my belief is that if the people of Quebec were offered a credible plan for their own currency, there may have actually been a ‘Yes’ victory in the October 1995 referendum, and by a significant margin. Although it may not solve all the problems faced by Quebeckers, I wish to propose such a plan. This is a viable plan in which the new currency is supported without any additional income tax, sales tax, or any other transaction tax that could diminish the economic welfare of the community. Additionally, the new currency will be established in such a way as to move the Quebec economy closer to both price stability and full employment, as well as favor very low interest rates. And, last but not least, the plan for this new currency unit, which, lacking a better term, I shall call “La Fleur”, is something every citizen can understand, and economists endorse.

The plan begins with the requirement that, in the eventuality of Quebec accession to independence, hence forth all new taxes would be payable in Quebec Fleurs. Only outstanding past tax liabilities would be payable in Canadian dollars. Since sales taxes and other transactions taxes, including the infamous GST, tend to discourage people from exchanging goods and services with each other, and require enormous record keeping and enforcement costs, they will be immediately eliminated. Instead, I propose a national property tax. Of course, since land is immobile, in one way or another everyone would pay a property tax, either directly by owners of landed property or in the form of higher rents.

The national property tax would be payable only in Fleurs. No record keeping would be necessary, beyond the current property registration system. If the tax isn’t paid, the government would simply sell the property regardless of who the owner is. Of course, the fiscal authority could decide to permit tax exemptions, such as for charitable contributions, should the electorate so desire. Notice, however, that the tax is payable in Fleurs, but no one yet has any Fleurs, except the new State of Quebec, which it can issue them as it desires. The population, and particularly property owners, will be willing sellers of real goods and services in exchange for needed Fleurs. The value of the Fleur will be whatever the government decides it is willing to pay for what it wishes to buy, as it knows the private sector needs its Fleurs to pay the new taxes.

Let’s stop here and examine a few things: 1) The State of Quebec can’t collect any Fleurs until AFTER it spends them, as no one has any to begin with. 2) In contrast to the conventional view peddled by politicians, the State does not tax to collect Fleurs so it can spend them. It taxes so that the private sector will need Fleurs, and therefore be willing sellers of real goods and services in exchange for needed Fleurs. 3) The government can expect to spend AT LEAST as many Fleurs as the private sector needs to pay its taxes. 4) The government will likely be able to spend more Fleurs, at the prices it wishes to pay, than exactly the amount needed for tax payments, as any Fleurs desired to be held by the public as, say, pocket cash must be left over after taxes are paid.

In order effectively to anchor the new currency unit, I further propose that the State first set a wage that it will pay to anyone willing to work for the State.(1) The effect of this government commitment would be essentially to eliminate involuntary unemployment and establish a minimum wage without any further legislation or intrusion into the private sector. This also effectively sets a value for the Fleur in terms of labor time. The market can be left to base all other pricing decisions when purchasing or selling other goods and services on the alternative universally available means of obtaining the Fleur- denominated basic State service. Here I will introduce a bit of arithmetic to illustrate how the State will get the real goods and services it needs to properly run the new nation. Let’s assume a hypothetical example where the consolidated new property and income taxes total 100 billion Fleurs. The State can expect to be able to spend at least that amount as the property owners have no other means of obtaining Fleurs. If the State offered 10,000 Fleurs as the basic State service wage, and spent nothing else, it could be reasonably sure at least 10 million workers would apply for the basic state job (100 billion divided by 10,000=10 million). Well, the State doesn’t want 10 million basic workers (especially since in the present hypothetical case the number would exceed the current population of Quebec!), but it does want other things that will be offered for sale by the private sector (as alternative ways of earning Fleurs to pay taxes). Let’s say the State spends 99 billion Fleurs at market prices, buying the other things that it really needs, including specialized labor and materials needed for the legal system, defense, education, health care and other government services. The private sector now needs only 1 billion more Fleurs to pay its taxes, so a minimum of only 10,000 basic workers can be relied on to apply for work. Of course, there will be a desire in the private sector for cash in circulation, and other activities that cause a desire to net save. This is generally a substantial amount. Suppose it amounts to a desire to earn another 5 billion Fleurs. This will be evidenced by another 500,000 basic wage earners applying for government jobs, for a total of 600,000. In any case, the more the State spends at market prices, the fewer the number of basic State job seekers. If there are what is deemed too many basic State job seekers, taxes can be lowered or other State spending increased until the number of basic State workers falls to the desired level.

What about interest rates? With this system, the State doesn’t have to pay interest, even when it spends more than it taxes. Notice that the State does not have to borrow in order to spend more than it taxes, as it simply issues currency, or credits someone’s bank account, when that person wishes to sell something in exchange for Fleurs. The key is that there is price stability as long as the State doesn’t spend so much at market prices that no workers apply for the basic job. In other words, there is price stability as long as the State doesn’t spend more Fleurs than the taxpayers determine they want. And, because the State always requires that at the margin State service is necessary to get needed Fleurs, the value of the Fleur is equal to the value of the labor time of the person who has to work at the basic State job to get the Fleurs.

When the State does spend more than it taxes, the extra Fleurs will likely settle as excess deposits in the banking system. This is an imbalance that any economist will tell you will result in ultra low short term interest rates, perhaps even a bit lower than seen in Japan during recent years. The prime rate, for example, could be expected to be around 3 1/2%. The bank regulators will of course have to continue to maintain their strict capital guidelines and credit requirements to prevent banks from speculating with insured depositors’ money, as they do today. If the State should desire higher interest rates for any reason, it always has the option of offering to pay a desired base rate of interest on excess bank deposits held at the central bank.

With this basic plan, the new State of Quebec could establish and maintain its own currency. The State would be able to purchase that which it requires to run the nation and simultaneously maintain full employment and price stability. There would also be an automatic increase in real prosperity associated with the elimination of the dampening side effects of sales taxes, which include restricted transactions, compliance costs, and enforcement costs. There would be no reason to restrict free trade, especially under NAFTA, and the State would allow the Fleur to trade freely as well. While undoubtedly facing initial speculation in the foreign exchange markets, ultimately the value of the Fleur would be established by what it can buy — the basic State job. And improving the value of those State workers through education, health care, etc. would serve to improve the value of the Fleur in the long run.

I would like to thank Professor Mario Seccareccia for his assistance.

Notes:

(1). I have elaborated a very precise plan which has been widely debated during the last year in both academic and and non-academic circles in the United States on exactly this question of government as employer of last resort. Please consult “Soft Currency Economics” for further details.

Warren B. Mosler

July 17, 1997

Yes I certainly remember that paper! As you say, Pierre Paquette and I had done a translation of it and it was eventually published in the well-ranked daily newspaper, Le Devoir, during that year. But I do not have the exact reference now. It was almost fourteen years ago! As they say in Quebec, « Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose »! [The more things change, the more they stay the same!]

Best,

Mario

how crowded is the short dollar trade?

Long gold, stocks, and other currencies is all the same trade, and all the specs and trend followers are in big, proving once again that the crowd isn’t always wrong.

Lack of understanding of what QE actually is seems to have scared everyone from portfolio managers and the man on the street to Putin to take action.

And Chairman Bernanke’s recent remarks, though fundamentally sound, gave them no comfort whatsoever, and only encourage this latest round of dollar selling and related trades.

No telling how long it will keep going.

But underneath it all the dollar’s fundamentals aren’t all that bad relative to the other currencies, apart from rising crude prices keeping the US import bill higher than otherwise, though partially offset by higher export prices, including food.

At last look trade gaps look to be ‘deteriorating’ in the eurozone, the UK, Japan, Canada, and Australia, as their currencies continue to climb, indicating they may have gotten past the humps in their J curves and trade flows have turned against them?

So looks to me like with the entire dollar move predominately driven by ‘hot money’ in the broad sense, there is nothing fundamental to get in the way of the reversal scenario suggested at the end of this article.

Best way to play it? Stay out of the way.

Cheap Dollar Fuels One-Way Bets in Everything Else

By Reuters

April 28 (Bloomberg) — Americans’ cheap money spigot remains open and the flow is as fast as ever, meaning the world had better brace for even higher oil, metals and food prices and a weaker dollar.

The clear message from Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke on Wednesday was that the U.S. central bank intends to keep interest rates exceptionally low and monetary policy very easy as it continues to try to inflate the U.S. economy back to health.

For investors, he offered further encouragement to keep borrowing in dollars, paying virtually nothing and then swapping those dollars into higher-yielding currencies or using them to buy oil, metals and food futures and options.

This so-called “carry trade” has become the trade du jour, particularly with the dollar’s precipitous drop of around 10 percent from its peak in January.

By comparison, U.S. crude futures are up 23 percent so far this year and the Thomson Reuters-Jefferies CRB index, a global index of commodities, is up 10 percent.

“The biggest risk right now is that Bernanke’s looseness creates the unintended consequence of boom-goes-bust, where easy-money-driven asset bubbles implode and confidence is consequently sucked out of the economy,” said JR Crooks, chief of research at investment advisory firm Black Swan Capital in Palm City, Florida.

“It’s one thing to have a currency on the decline; it’s another thing to have GDP on the decline.”

The “carry” trading tack is akin to the still popular yen-carry trade, which involves borrowing yen at Japan’s near-zero interest rates to purchase other higher-yielding securities such as Treasuries. Investors are borrowing in currencies like the dollar to fund purchases in markets with higher yields or currencies with potentially higher returns.

The Barclays’ G10 carry excess return index shows that borrowing in low-yielding currencies such as the greenback and buying those with high interest rates like the Australian dollar has generated returns of about 37 percent so far since the end of the financial crisis in early 2009.

“The Fed seems to be in no rush to tighten monetary policy. So if rates remain low, why shouldn’t the dollar be the preferred funding currency?” said Thomas Stolper, chief currency strategist at Goldman Sachs in London.

“And as you know in foreign exchange, it’s all about differentials between countries and in that respect, that differential is negative for the dollar,” Stolper added.

The yield differential continues to weigh against the dollar, particularly against the euro , the Australian dollar, and some emerging market currencies, whose central banks have started to raise interest rates.

Record low U.S. rates of zero to 0.25 percent, an enormous supply of liquidity under the Fed’s purchases of more than $2 trillion of Treasury and mortgage bonds, and improving economic prospects in emerging markets have prompted investors to borrow the lower-yielding dollar in carry trades over the last 18 months.

A rough estimate from investment advisory firm Pi Economics in Stamford, Connecticut, showed that the Fed’s easing may have fueled dollar carry trades in excess of $1 trillion, based on U.S. financial institutions’ net foreign assets positions.

On Wednesday, the dollar skidded to a three-year low of 73.284 as measured by the Intercontinental Exchange’s dollar index, down around 10 percent from its peak in January. Many traders expect the index to fall through the all-time low, hit in July 2008, of 70.698.

Feasible Alternative

For some investors, using the dollar in carry trades remains the only feasible alternative to other low-yielding currencies such as the yen and Swiss franc .

While the yen yields an interest rate of zero, like the dollar, the Japanese currency could strengthen if the economy goes into recession. Since Japan has huge overseas investments, a recession would prompt a repatriation of domestic investors’ funds to bolster savings, boosting the yen.

The Swiss economy is in much better shape than the United States and a rise in inflation there could well prompt the Swiss National Bank to raise interest rates, much like the European Central Bank did early this month.

That leaves the U.S. dollar as the only other option left to finance investors’ penchant for risk-taking.

“No one really thinks the Fed will hike rates significantly … They would want to keep rates low since the recovery is not that strong,” said Pablo Frei, a portfolio manager and senior analyst at Quaesta Capital, a Zurich-based fund of funds focused on currency managers, with assets under management of about $3.5 billion.

Frei said that although the dollar is a big short among hedge funds, “people have become more cautious of the risk of the dollar carry,” given how crowded this trade has become.

He added that the fund managers he tracks have reduced their short position on the dollar, although the lower-dollar bet remains their largest exposure.

As in any crowded trade, there is always the risk of a squeeze once things get sour, which could lead to a massive unwinding of carry trades and the potential for huge losses for those slow to get out. When global stocks drop, or when the risk barometer shoots up, investors tend to repatriate funds, close out losing carry trades and buy back currencies they had shorted.

This happened in 2008 during the global financial crisis and could well happen again.