The big stupid continues uninterrupted from regime to regime:

By John Lounsburry

Nov 15 (Econintersect) — Econintersect: This lecture was presented to the inaugural session of the Liberty Restoration Foundation in Orlando, FL October, 2011.

Stephen Bannon, the CEO of Donald Trump’s successful presidential campaign and to-be Chief Strategist in the Trump White House, describes his view of what is wrong with America in 2011. He maintains that:

The U.S. cannot meet its future obligations.

The Fed makes payments by crediting member bank accounts. There is no operational constraint on this process

Government spending is sucking money out of “everything else”.

Government spends via the fed crediting a member bank account. Total dollar bank balances are increased by exactly that amount. Nothing is ‘sucked out’.

The trade deficit is the “beating heart” of our economic problems.

As for the trade deficit, imports are real benefits, exports real cost. Real wealth is domestic production + imports – exports. It’s the policy response to imports that turns a good thing into a bad thing, not the import per se. When unemployment goes up due to imports (or for any other reason), the constructive policy response is to support aggregate demand/sales/output/employment with a fiscal adjustment – lower taxes or higher public spending. That is, net imports give a nation ‘fiscal space’ to make a fiscal adjustment that sustains domestic full employment, and with better jobs than the ones that were lost. And that way we also optimize what’s called our ‘real terms of trade’, which is what we can import vs what we have to export.

The Tea Party understands what’s wrong with America because members know the price of a bag of groceries.

Whatever!!!

We are passing on zero net worth to our children.

The public debt is the total dollars spent by govt that have not yet been used to pay taxes, which constitutes the net financial assets of the economy, aka ‘net nominal dollar savings’ of the economy.

This man is the new president’s Chief Strategist.

Mercy…. :(

FROM DB:

A reform of the US corporate tax code is very high on Donald Trump’s agenda. With trillions of American corporate profits sitting offshore due to punitive repatriation rates, a potential change in policy could have material market implications. In this report we attempt to answer some frequently asked questions on the topic. While the amounts involved may be smaller than what is commonly assumed, we argue there would be material implications for both the dollar and particularly the cost of dollar funding. In the event the tax reform is permanent, it is the absence of a future pool of reliable dollar liquidity for European and other foreign banks that will likely have the biggest impact in particular.

Link: http://pull.db-gmresearch.com/p/11390-5D2D/86468804/DB_SpecialReport_2016-11-17_0900b8c08c0effb3.pdf

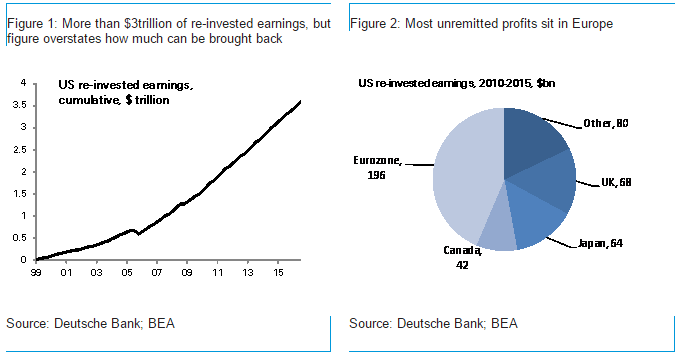

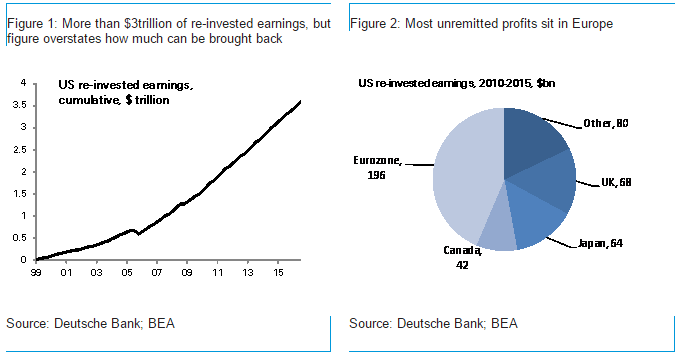

1. How much offshore earnings can US corporates bring back?

Answer: about $1 trillion

It is important to distinguish between unrepatriated earnings and cash. A substantial portion of US profits are re-invested into foreign operations and capital expenditure and are therefore very sticky. Cash and liquid assets are a subset of unrepatriated earnings and are the most relevant metric to look at: it is this pool of dormant savings that is the most likely to be brought back to the US in the event of a change in tax treatment.

How big are the numbers? The upper bound can be calculated by looking at re-invested earnings from the US national accounts. Cumulative re-invested earnings since 1999 currently stand at more than $3 trillion according to the BEA (chart 1). The number is not reflective of the amounts that can be brought back however. A bottom up analysis of S&P 500 companies by our equity analysts estimates that the total amount of liquid assets held offshore is closer to $1 trillion.* We would consider this as a reasonable lower bound given that S&P 500 reporting companies only account for a portion of US total market capitalization but include the vast majority of US listed multinationals. The number is also broadly consistent in order of magnitude with the “currency and deposits” item on the US international investment position, currently about $1.7trn

2. What currency are these earnings denominated in?

Answer: 90% is probably in dollars

It is difficult to provide an accurate answer to this question because the vast majority of companies don’t outline the currency composition of their holdings. Three of the largest tech companies that disclose some detail indicate that the majority of foreign earnings are already denominated in dollars. Oracle has an explicit currency breakdown in its reports with 10% of offshore profits denominated in foreign currency. Microsoft has a similar breakdown. Apple states that foreign subsidiary cash is “generally based in US dollar-denominated holdings” but doesn’t give a figure. Broadly speaking, expectations of a medium-term dollar appreciation trend, poorly yielding alternatives, the desire to avoid balance sheet mismatches and the availability of dollar-denominated assets offshore all point to most foreign profits as already being converted into USD.

3. Where are these earnings located?

Answer: mostly in Europe

Data on the location of foreign unrepatriated cash is also hard to come by. A top-down metric can be obtained from the BEA re-invested earnings data broken down by region. Cumulating earnings over the last five years, we find that the vast majority is located in the Eurozone, followed by the UK. An alternative bottom-up analysis that looked at IRS data and earnings of Fortune 500 companies leads to the same conclusion, with most profits held in the Netherlands, Ireland and Luxembourg.**

4. How much of the earnings are in cash?

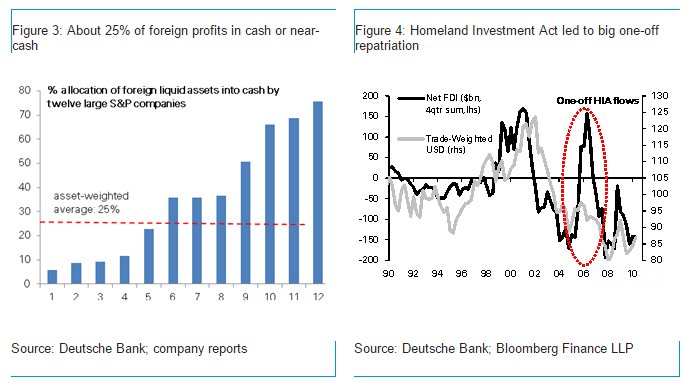

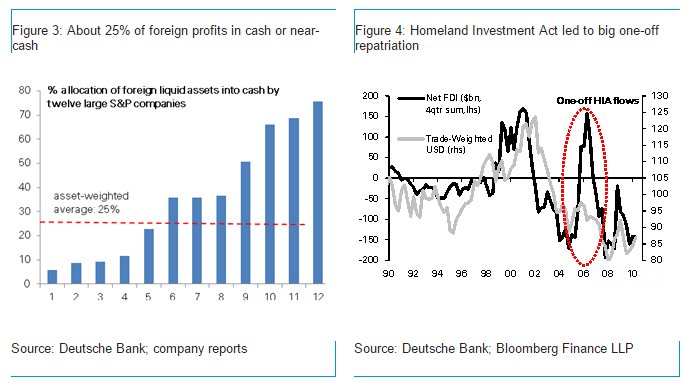

Answer: probably about 25%, with the rest in other financial assets, mostly US fixed income

Whether corporate profits are held in cash compared to other liquid assets has important market implications. There is no top-down data available, but our analysis of twelve companies with some of the largest offshore cash balances suggests that close to 75% of balances are in investments, and only 25% are held in cash or cash equivalents. These primarily consist of deposits held at major banks, tier-1 commercial paper and money market instruments with original maturities of less than 90 days. The securities that these companies invest tend to be liquid, short term instruments.

For instance, 83% of Microsoft’s investments consisting of US government and agency securities. Similarly, Oracle’s investments are ‘generally held with large, diverse financial institutions’ that meet investment grade criteria. All securities are ‘high quality’ with 28% having maturities within a year and 72% having maturities between 1-6 years.

5. What are the market implications?

Answer: it depends on the US corporate tax reform. Positive for the dollar and negative for dollar funding. The impact is less than the headline numbers suggest but still material given how large the numbers involved are.

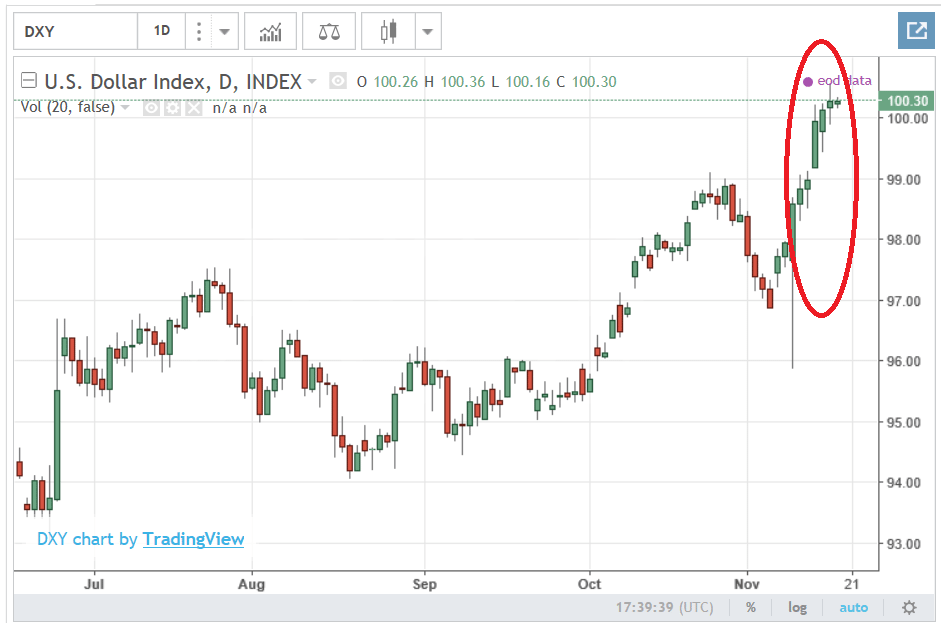

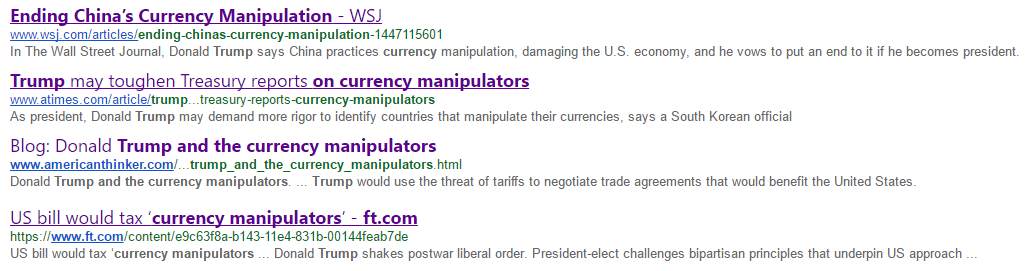

The closest parallel to the impact of corporate tax repatriation is the 2005 US Homeland Investment Act (HIA). This temporarily allowed companies to bring back foreign profits at a 5.25% tax rate. US FDI spiked during that year and the dollar rallied by 7%. A number of lessons can be learnt from that episode. First, a temporary tax holiday is likely to have a more material upfront impact as it would force repatriation within a shorter time frame. A permanent change would lessen the immediate impact but is likely to be bigger medium-term as it would apply to future earnings as well. Second, the tax rate applied to foreign earnings matters. The lower this is the bigger the likely repatriation. Finally, the broader context and market narrative matters: a number of positive dollar stories took place in 2005, inclusive of a Fed hiking cycle.

First, a 7% dollar rally for the year isn’t all that much, and it reads like even DB agrees it can be attributed to other factors.

We see a corporate tax reform as having a material impact on both the dollar and the cost of dollar funding.

Dollar The indirect impact on the dollar is just as important as the direct “conversion” impact. With 90% of profits already held in the greenback we are left with an (upper bound) estimate of 100bn dollars that may need to be converted. Even if much smaller than the headline reported and even if a smaller portion is converted, this amount is material compared to an annual US current account deficit of $500bn. More importantly, the second-order effect may be even greater. A profit repatriation that boosts business confidence and is deployed into capital spending will be positive for the dollar via higher growth and Fed expectations.

First, earnings can be ‘repatriated’ without converting anything, as my understanding is it’s just a matter of reporting and accounting for the dollar value of past earnings as domestic income.

Second, I see no reason why any company would increase capital spending just because foreign earnings from past years are suddenly accounted for as domestic earnings at a lower tax rate. DB is implying that companies have been deferring capital spending due to current tax law, even with adequate liquidity and access to funding.

Tighter funding, wider cross-currency basis Even if foreign profits are held in dollars, the impact on the cost of offshore dollar funding can be material if a repatriation shifts liquidity away from European and other foreign banks to the US. The implication is that cross-currency dollar basis would be pushed wider. Our bottom-up analysis in section 4 suggests that about 250bn dollars currently sit in cash or near-cash dollar liquidity that has the potential to be moved back to the US. Compared to the approximately 200bn withdrawal of dollar liquidity from Eurozone and Japanese prime money market issuers following recent US reforms the amounts are material. Most importantly, this is likely a lower bound on the potential liquidity impact. While corporate may be able to shift the custodial location of Treasury holdings onshore without pulling liquidity from offshore banking systems, it is not clear this can be achieved for asset manager mandates or holdings of non-US resident issuers such as Eurodollar corporate bonds. In the event that the corporate tax reform is permanent, it is likely the absence of future dollar liquidity from US corporate profits will have the most material medium-term impact: approximately 300bn of US earnings are re-invested each year, and the shift of parts of this flow of reliable dollar liquidity to the US would be a negative supply shock for offshore dollar funding.

Allow an example: assume a client has $100 billion in DB NYC, and $100 billion in DB London. Repatriation simply means he shifts the $100 billion in his DB London account to DB NYC account. And DB now has the entire $200 billion in its account at the Fed. DB’s overall liquidity has not changed. And if a DB client in the Euro zone wants to borrow $ from DB, DB is just as able to make that loan as before the repatriation.

[The author would like to acknowledge Suhaib Chowdhary for his invaluable assistance]

George Saravelos

FX Research

Deutsche Bank AG, Filiale London

Global Markets

1 Great Winchester Street, EC2N 2DB, London, United Kingdom

Tel. +44 20 754-79118

My conclusion remains. Repatriation as a source of funds is being grossly over estimated

Trump has been big (huge) on threatening the likes of China with currency manipulation, aka yuan depreciation vs the $. Same with yen, euro, etc. all threatening the Trump rust belt revival constituency, etc.

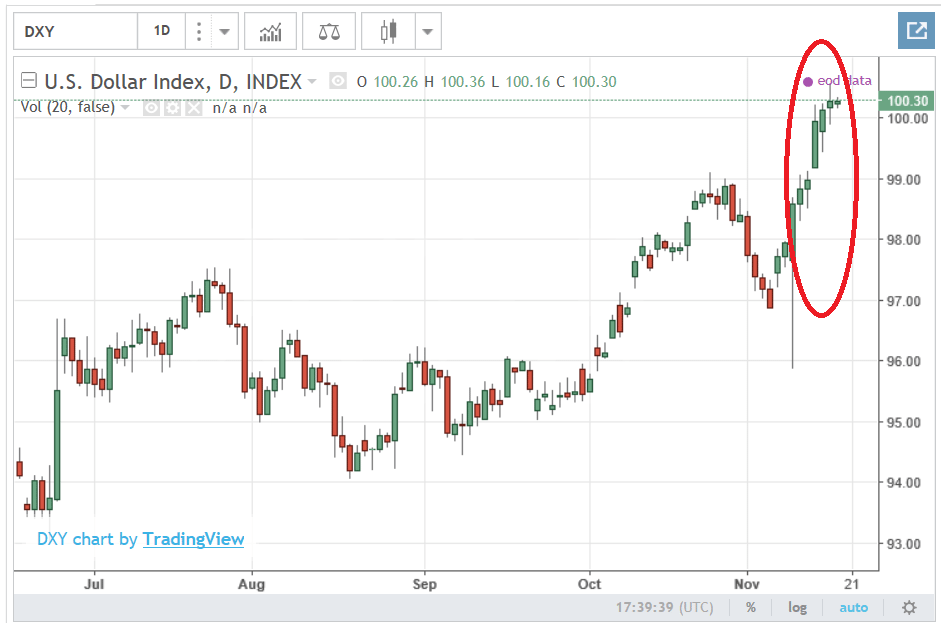

So now, a week after his election, the gauntlet has been throw, as the $US reaches new highs, and I suspect we’ll soon see how the big guy responds: