My proposals remain:

1. A full FICA suspension:

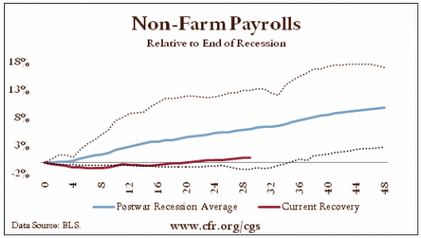

The suspension of FICA paid by employees restores spending which supports output and employment.

The suspension of FICA paid by business helps keep costs down which in a competitive environment lowers prices for consumers.

2. $150 billion one time distribution by the federal govt to the states on a per capita basis to get them over the hump.

3. An $8/hr federally funded transition job for anyone willing and able to work to assist in the transition from unemployment to private sector employment.

Call me an inflation hawk if you want. But when the fiscal drag is removed with the FICA suspension and funds for the states I see risk of what will be seen as ‘unwelcome inflation’ causing Congress to put on the brakes long before unemployment gets below 5% without the $8/hr transition job in place, even with the help of the FICA suspension in lowering costs for business.

It’s my take that in an expansion the ’employed labor buffer stock’ created by the $8/hr job offer will prove a superior price anchor to the current practice of using the current unemployment based buffer stock as our price anchor.

The federal government caused this mess for allowing changing credit conditions to cause its resulting over taxation to unemploy a lot more people than the government wanted to employ. So now the corrective policy is to suspend the FICA taxes, give the states the one time assistance they need to get over the hump the federal government policy created, and provide the transition job to help get those people that federal policy is causing to be unemployed back into private sector employment in a more orderly, more ‘non inflationary’ manner.

I’ve noticed the criticism the $8/hr proposal- aka the ‘Job Guarantee’- has been getting in the blogosphere, and it continues to be the case that none of it seems logically consistent to me, as seen from an MMT perspective. It seems the critics haven’t fully grasped the ramifications of the recognition of the currency as a (simple) public monopoly as outlined in Full Employment AND Price Stability and the other mandatory readings.

So yes, we can simply restore aggregate demand with the FICA suspension and funds for the states, but if I were running things I’d include the $8 transition job to improve the odds of both higher levels of real output and lower ‘inflation pressures’.

Also, this is not to say that I don’t support the funding of public infrastructure (broadly defined) for public purpose. In fact, I see that as THE reason for government in the first place, and it should be determined and fully funded as needed. I call that the ‘right size’ government, and, in general, it’s not the place for cyclical adjustments.

4. An energy policy to help keep energy consumption down as we expand GDP, particularly with regard to crude oil products.

Here my presumption is there’s more to life than burning our way to prosperity, with ‘whoever burns the most fuel wins.’

Perhaps more important than what happens if these proposals are followed is what happens if they are not, which is more likely going to be the case.

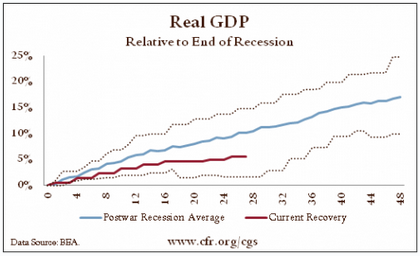

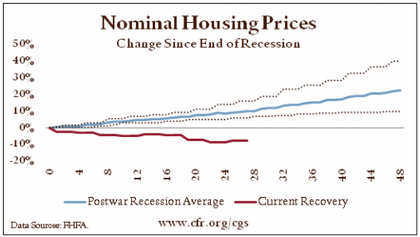

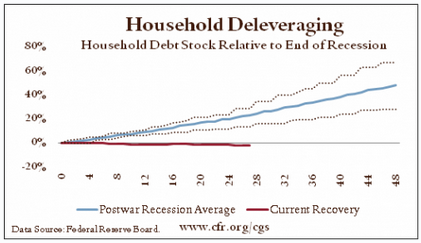

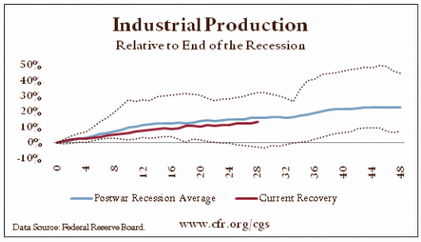

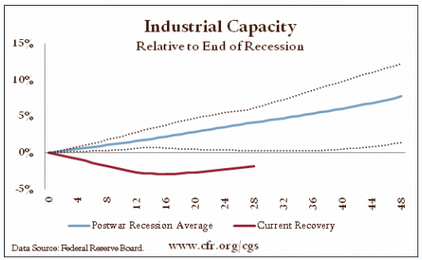

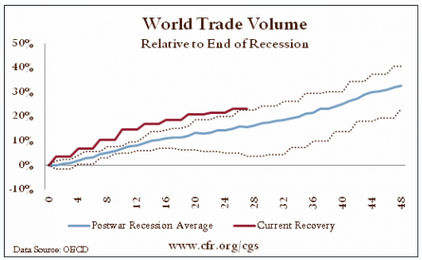

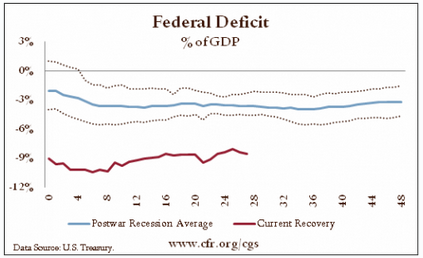

First, given current credit conditions, world demand, and the 0 rate policy and QE, it looks to me like the current federal deficit isn’t going to be large enough to allow anything better than muddling through we’ve seen over the last few years.

Second, potential volatility is as high as it’s ever been. Europe could muddle through with the ECB doing what it takes at the last minute to prevent a collapse, or doing what it takes proactively, or it could miss a beat and let it all unravel. Oil prices could double near term if Iran cuts production faster than the Saudis can replace it, or prices could collapse in time as production comes online from Iraq, the US, and other places forcing the Saudis to cut to levels where they can’t cut any more, and lose control of prices on the downside.

In other words, the risk of disruption and the range of outcomes remains elevated.