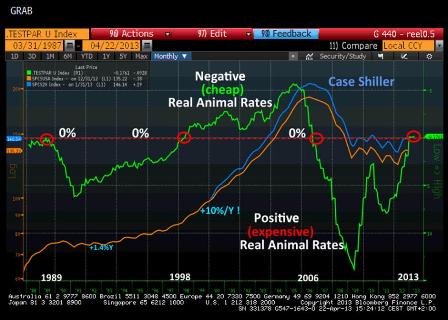

As previously discussed, financial placebos like QE do cause market participants to alter behavior out of either a misunderstanding of the actual fundamentals, or in anticipation of reactions by others presumed to be misinformed. And while the effects of these activities get reversed, however sometimes the effects are more lasting.

And there are also first order and second order effects. For example, a QE announcement could unleash misinformed fears about ‘money printing’ and ‘currency debasement’ and subsequent portfolio shifting that drives down the currency in the fx markets and drives up the price of gold. And the same misguided fears could cause bond yields to go higher in anticipation of a stronger/inflationary economy, even with the Fed buying bonds in an attempt to take yields lower.

So right now the QE/’monetary policy works if large enough’ placebo is at least partially driving things in both Japan and the US, and today’s announcement of the possibility of the ECB buying asset backed securities is now also at work.

And along the same lines but with a different ‘sign’ is the ideologically driven idea that cutting govt spending in the face of a large output gap- the sequester- is a plus for output and employment. Same for the year end tax hikes.

The underlying fundamental I don’t see discussed is whether private sector credit expansion can continue to sufficiently ‘overcome’ the declining govt deficit spending and satisfy the ‘savings desires’/demand leakages.

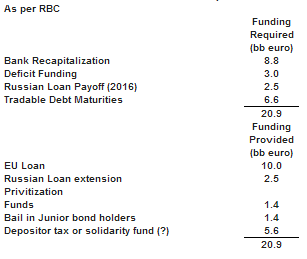

The main sources of private sector credit expansion are housing, student loans ($9 billion increase in March), and cars. Since 2009, the private sector credit expansion has managed to stay far enough ahead of the declining govt deficit, which has fallen from about 9% of GDP to about a rate of 6% of GDP by year end (mainly via the ‘automatic fiscal stabilizers’ of higher tax receipts and moderating transfer payments) resulting in about 2% real growth.

The question now is whether the private sector credit expansion can survive the 1.25% of GDP shock of the FICA tax hike and sequesters- which reduce support from the govt deficit to only maybe 4.5% of GDP- and still continue to sufficiently feed the (ever growing) demand leakages enough to generate positive GDP growth.

The stock market is often the best leading indicator of the macro economy, but it has ‘paused’ for two double dips that didn’t happen over the last few years, and it is subject to influence from placebos. Additionally, valuations change as implied discount rates change, and so in this case P/E’s shifting upwards may be discounting interest rates staying low for longer, due to an economy too weak to trigger Fed rate hikes, but strong enough to keep sales and earnings at least flat.

Placebo Surgery Shows Surprising Results

By Kate Melville

Research by Doctor Cynthia McRae of the University of Denver’s College of Education provides strong evidence for a significant mind-body connection among patients who participated in a Parkinson’s surgical trial.

Forty persons from the United States and Canada participated to determine the effectiveness of transplantation of human embryonic dopamine neurons into the brains of persons with advanced Parkinson’s disease. Twenty patients received the transplant while 20 more were randomly assigned to a sham surgery condition. Dr. McRae reports that the “placebo effect” was strong among the 30 patients who participated in the quality of life portion of the study.

“Those who thought they received the transplant at 12 months reported better quality of life than those who thought they received the sham surgery, regardless of which surgery they actually received,” says Dr. McRae. More importantly, objective ratings of neurological functioning by medical personnel showed a similar effect. In the report, appearing in the Archives of General Psychiatry, Dr. McRae writes “medical staff, who did not know which treatment each patient received, also reported more differences and changes at 12 months based on patients’ perceived treatment than on actual treatment.”

One patient reported that she had not been physically active for several years before surgery, but in the year following surgery she resumed hiking and ice skating. When the double blind was lifted, she was surprised to find that she had received the sham surgery.

Although patient perceptions influenced their test scores, when the total sample of patients was grouped by the actual operation they received, patients who had the actual transplant surgery showed improvement in movement while, on average, patients who had sham surgery did not.

Professor Dan Russell at Iowa State, the study’s co-author, says the findings have both scientific and practical implications. “This study is extremely important in regard to the placebo effect because we know of no placebo studies that have effectively maintained the double-blind for at least 12 months. The average length of placebo studies is eight weeks,” according to Russell. Dr. McRae notes that similar results related to the placebo effect have been found in other studies with patients with Parkinson’s disease. She says that there is a need for placebo controls in studies evaluating treatment for Parkinson’s as the placebo effect seems to be very strong in this disease. Dr. McRae also reports that although the sham surgery research design is somewhat controversial and has raised some ethical concerns, the results of this study show “the importance of a double-blind design to distinguish the actual and perceived values of a treatment intervention.”

Knee Surgery Proves No Better Than Placebo

By Katrina Woznicki

July 10, 2002 (UPI) — For individuals suffering from osteoarthritis in their knees, a common type of knee surgery has been found to be no more beneficial than a placebo, a new study revealed Wednesday.

Researchers at the Houston VA Medical Center and at Baylor College of Medicine came to this surprising conclusion after comparing various knee treatments to placebo surgery on 180 patients with knee pain.

The patients were randomly divided into three groups. One group underwent debridement, in which the damaged or loose cartilage is the knee is surgically removed by an arthroscope, a pencil-thin tube that allows doctors to see inside the knee. The second group received arthoscopic lavage, which flushes out the bad cartilage from the healthier tissue. A third group underwent a placebo surgery. They were sedated by medication while surgeons simulated arthroscopic surgery on their knees by making small incisions on the leg, but not removing any tissue.

During a two-year follow-up, researchers found no differences among the three groups. All patients reported improvement in their symptoms of pain and ability to use their knees. Throughout the two years, patients were unaware whether they had received the “real” or placebo surgery.

However, patients who received actual surgical treatments did not report less pain or better functioning of their knees compared to the placebo group. In fact, periodically during the follow-up, the placebo group reported a better outcome compared to the patients who underwent debridement.