Lessons from Crises, 1985-2014

Stanley Fischer[1]

It is both an honor and a pleasure to receive this years SIEPR Prize. Let me list the reasons. First, the prize, awarded for lifetime contributions to economic policy, was started by George Shultz. I got my start in serious policy work in 1984-85, as a member of the advisory group on the Israeli economy to George Shultz, then Secretary of State. I learned a great deal from that experience, particularly from Secretary Shultz and from Herb Stein, the senior member of the two-person advisory group (I was the other member). Second, it is an honor to have been selected for this prize by a selection committee consisting of George Shultz, Ken Arrow, Gary Becker, Jim Poterba and John Shoven. Third, it is an honor to receive this prize after the first two prizes, for 2010 and for 2012 respectively, were awarded to Paul Volcker and Marty Feldstein. And fourth, it is a pleasure to receive the award itself.

When John Shoven first spoke to me about the prize, he must have expected that I would speak on the economic issues of the day and I would have been delighted to oblige. However, since then I have been nominated by President Obama but not so far confirmed by the Senate for the position of Vice-Chair of the Federal Reserve Board. Accordingly I shall not speak on current events, but rather on lessons from economic crises I have seen up close during the last three decades and about which I have written in the past starting with the Israeli stabilization of 1985, continuing with the financial crises of the 1990s, during which I was the number two at the IMF, and culminating (I hope) in the Great Recession, which I observed and with which I had to deal as Governor of the Bank of Israel between 2005 and 2013.

This is scheduled to be an after-dinner speech at the end of a fine dinner and after an intensive conference that started at 8 a.m. and ran through 6 p.m. Under the circumstances I shall try to be brief. I shall start with a list of ten lessons from the last twenty years, including the crises of Mexico in 1994-95, Asia in 1997-98, Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999-2000, Argentina in 2000-2001, and the Great Recession. I will conclude with one or two-sentence pieces of advice I have received over the years from people with whom I had the honor of working on economic policy. The last piece of advice is contained in a story from 1985, from a conversation with George Shultz.

I. Ten lessons from the last two decades.[2]

Lesson 1: Fiscal policy also matters macroeconomically. It has always been accepted that fiscal policy, in the sense of the structure of the tax system and the composition of government spending, matters for the behavior of the economy. At times in the past there has been less agreement about whether the macroeconomic aspects of fiscal policy, frequently summarized by the full employment budget deficit, have a significant impact on the level of GDP. As a result of the experience of the last two decades, it is once again accepted that cutting government spending and raising taxes in a recession to reduce the budget deficit is generally recessionary. This was clear from experience in Asia in the 1990s.[3] The same conclusion has been reached following the Great Recession.

Who would have thought?…

At the same time, it needs to be emphasized that there are circumstances in which a fiscal contraction can be expansionary particularly for a country running an unsustainable budget deficit.

Unsustainable?

He doesn’t distinguish between floating and fixed fx policy. At best this applies to fixed fx policy, where fx reserves would be exhausted supporting the peg/conversion. And as a point of logic, with floating fx this can only mean an unsustainable inflation, whatever that means.

More important, small budget deficits and smaller rather than larger national debts are preferable in normal times in part to ensure that it will be possible to run an expansionary fiscal policy should that be needed in a recession.

Again, this applies only to fixed fx regimes where a nation might need fx reserves to support conversion at the peg. With floating fx nominal spending is in no case revenue constrained.

Lesson 2: Reaching the zero interest lower bound is not the end of expansionary monetary policy. The macroeconomics I learned a long time ago, and even the macroeconomics taught in the textbooks of the 1980s and early 1990s, proclaimed that more expansionary monetary policy becomes either impossible or ineffective when the central bank interest rate reaches zero, and the economy finds itself in a liquidity trap. In that situation, it was said, fiscal policy is the only available expansionary tool of macroeconomic policy.

Now the textbooks should say that even with a zero central bank interest rate, there are at least two other available monetary policy tools. The first consists of quantitative easing operations up and down the yield curve, in particular central bank market purchases of longer term assets, with the intention of reducing the longer term interest rates that are more relevant than the shortest term interest rate to investment decisions.

Both are about altering the term structure of rates. How about the lesson that the data seems to indicate the interest income channels matter to the point where the effect is the reverse of what the mainstream believes?

That is, with the govt a net payer of interest, lower rates lower the deficit, reducing income and net financial assets credited to the economy. For example, QE resulted in some $90 billion of annual Fed profits returned to the tsy that otherwise would have been credited to the economy. That, with a positive yield curve, QE functions first as a tax.

The second consists of central bank interventions in particular markets whose operation has become significantly impaired by the crisis. Here one thinks for instance of the Feds intervening in the commercial paper market early in the crisis, through its Commercial Paper Funding Facility, to restore the functioning of that market, an important source of finance to the business sector. In these operations, the central bank operates as market maker of last resort when the operation of a particular market is severely impaired.

The most questionable and subsequently overlooked ‘bailout’- the Fed buying, for example, GE commercial paper when it couldn’t fund itself otherwise, with no ‘terms and conditions’ as were applied to select liquidity provisioning to member banks, AIG, etc. And perhaps worse, it was the failure of the Fed to provide liquidity (not equity, which is another story/lesson) to its banking system on a timely basis (it took months to get it right) that was the immediate cause of the related liquidity issues.

However, and perhaps the most bizarre of what’s called unconventional monetary policy, the Fed did provide unlimited $US liquidity to foreign banking systems with its ‘swap lines’ where were, functionally, unsecured loans to foreign central banks for the further purpose of bringing down Libor settings by lowering the marginal cost of funds to foreign banks that otherwise paid higher rates.

Lesson 3: The critical importance of having a strong and robust financial system. This is a lesson that we all thought we understood especially since the financial crises of the 1990s but whose central importance has been driven home, closer to home, by the Great Recession. The Great Recession was far worse in many of the advanced countries than it was in the leading emerging market countries. This was not what happened in the crises of the 1990s, and it was not a situation that I thought would ever happen. Reinhart and Rogoff in their important book, This Time is Different,[4] document the fact that recessions accompanied by a financial crisis tend to be deeper and longer than those in which the financial system remains operative. The reason is simple: the mechanisms that typically end a recession, among them monetary and fiscal policies, are less effective if households and corporations cannot obtain financing on terms appropriate to the state of the economy.

The lesson should have been that the private sector is necessarily pro cyclical, and that a collapse in aggregate demand that reduces the collateral value of bank assets and reduces the income required to support the credit structure triggers a downward spiral that can only be reversed with counter cyclical fiscal policy.

In the last few years, a great deal of work and effort has been devoted to understanding what went wrong and what needs to be done to maintain a strong and robust financial system. Some of the answers are to be found in the recommendations made by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision and the Financial Stability Board (FSB). In particular, the recommendations relate to tougher and higher capital requirements for banks, a binding liquidity ratio, the use of countercyclical capital buffers, better risk management, more appropriate remuneration schemes, more effective corporate governance, and improved and usable resolution mechanisms of which more shortly. They also include recommendations for dealing with the clearing of derivative transactions, and with the shadow banking system. In the United States, many of these recommendations are included or enabled in the Dodd-Frank Act, and progress has been made on many of them.

Everything except the recognition of the need for immediate and aggressive counter cyclical fiscal policy, assuming you don’t want to wait for the automatic fiscal stabilizers to eventually turn things around.

Instead, what they’ve done with all of the above is mute the credit expansion mechanism, but without muting the ‘demand leakages’/’savings desires’ that cause income to go unspent, and output to go unsold, leaving, for all practical purposes (the export channel isn’t a practical option for the heaving lifting), only increased deficit spending to sustain high levels of output and employment.

Lesson 4: The strategy of going fast on bank restructuring and corporate debt restructuring is much better than regulatory forbearance. Some governments faced with the problem of failed financial institutions in a recession appear to believe that regulatory forbearance giving institutions time to try to restore solvency by rebuilding capital will heal their ills. Because recovery of the economy depends on having a healthy financial system, and recovery of the financial system depends on having a healthy economy, this strategy rarely works.

The ‘problem’ is bank lending to offset the demand leakages when the will to use fiscal policy isn’t there.

And today, it’s hard to make the case that us lending is being constrained by lack of bank capital, with the better case being a lack of credit worthy, qualifying borrowers, and regulatory restrictions- called ‘regulatory overreach’ on some types of lending as well. But again, this largely comes back to the understanding that the private sector is necessarily pro cyclical, with the lesson being an immediate and aggressive tax cut and/or spending increase is the way go.

This lesson was evident during the emerging market crises of the 1990s. The lesson was reinforced during the Great Recession, by the contrast between the response of the U.S. economy and that of the Eurozone economy to the low interest rate policies each implemented. One important reason that the U.S. economy recovered more rapidly than the Eurozone is that the U.S. moved very quickly, using stress tests for diagnosis and the TARP for financing, to restore bank capital levels, whereas banks in the Eurozone are still awaiting the rigorous examination of the value of their assets that needs to be the first step on the road to restoring the health of the banking system.

The lesson remaining unlearned is that with a weaker banking structure the euro zone can implement larger fiscal adjustments- larger tax cuts and/or larger increases in public goods and services.

Lesson 5: It is critical to develop now the tools needed to deal with potential future crises without injecting public funds.

Yes, it seems the value of immediate and aggressive fiscal adjustments remains unlearned.

This problem arose during both the crises of the 1990s and the Great Recession but in different forms. In the international financial crises of the 1990s, as the size of IMF packages grew, the pressure to bail in private sector lenders to countries in trouble mounted both because that would reduce the need for official financing, and because of moral hazard issues. In the 1980s and to a somewhat lesser extent in the 1990s, the bulk of international lending was by the large globally active banks. My successor as First Deputy Managing Director of the IMF, Anne Krueger, who took office in 2001, mounted a major effort to persuade the IMF that is to say, the governments of member countries of the IMF to develop and implement an SDRM (Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism). The SDRM would have set out conditions under which a government could legally restructure its foreign debts, without the restructuring being regarded as a default.

The lesson is that foreign currency debt is to be avoided, and that legal recourse in the case of default should be limited.

Recent efforts to end too big to fail in the aftermath of the Great Recession are driven by similar concerns by the view that we should never again be in a situation in which the public sector has to inject public money into failing financial institutions in order to mitigate a financial crisis. In most cases in which banks have failed, shareholders lost their claims on the banks, but bond holders frequently did not. Based in part on aspects of the Dodd-Frank Act, real progress has been made in putting in place measures to deal with the too big to fail problem. Among them are: the significant increase in capital requirements, especially for SIFIs (Systemically Important Financial Institutions) and the introduction of counter-cyclical capital buffers for banks; the requirement that banks hold a cushion of bail-in-able bonds; and the sophisticated use of stress tests.

The lesson is that the entire capital structure should be explicitly at full risk and priced accordingly.

Just one more observation: whenever the IMF finds something good to say about a countrys economy, it balances the praise with the warning Complacency must be avoided. That is always true about economic policy and about life. In the case of financial sector reforms, there are two main concerns that the statement about significant progress raises: first, in designing a system to deal with crises, one can never know for sure how well the system will work when a crisis situation occurs which means that we will have to keep on subjecting the financial system to tough stress tests and to frequent re-examination of its resiliency; and second, there is the problem of generals who prepare for the last war the financial system and the economy keep evolving, and we need always to be asking ourselves not only about whether we could have done better last time, but whether we will do better next time and one thing is for sure, next time will be different.

And in any case an immediate and aggressive fiscal adjustment can always sustain output and employment. There is no public purpose in letting a financial crisis spill over to the real economy.

Lesson 6: The need for macroprudential supervision. Supervisors in different countries are well aware of the need for macroprudential supervision, where the term involves two elements: first, that the supervision relates to the financial system as a whole, and not just to the soundness of each individual institution; and second, that it involves systemic interactions. The Lehman failure touched off a massive global financial crisis, a reflection of the interconnectedness of the financial system, and a classic example of systemic interactions. Thus we are talking about regulation at a very broad level, and also the need for cooperation among regulators of different aspects of the financial system.

The lesson are that whoever insures the deposits should do the regulation, and that independent fiscal adjustments can be immediately and aggressively employed to sustain output and employment in any economy.

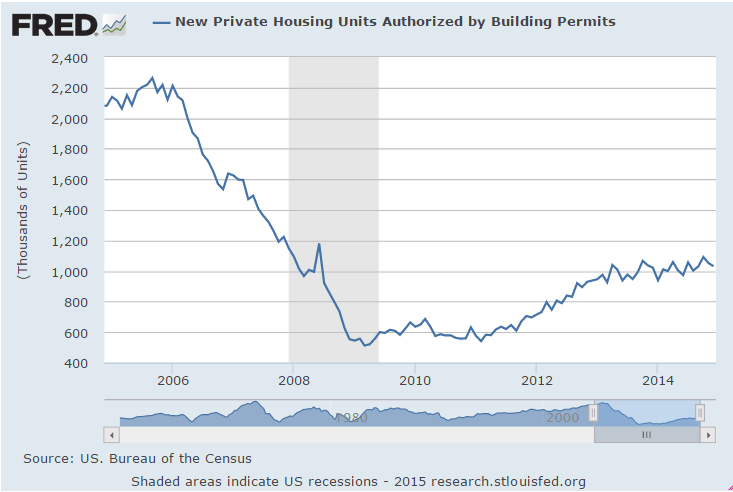

In practice, macroprudential policy has come to mean the deployment of non-monetary and non-traditional instruments of policy to deal with potential problems in financial institutions or a part of the financial system. For instance, in Israel, as in other countries whose financial system survived the Great Recession without serious damage, the low interest rate environment led to uncomfortably rapid rates of increase of housing prices. Rather than raise the interest rate, which would have affected the broader economy, the Bank of Israel in which bank supervision is located undertook measures whose effect was to make mortgages more expensive. These measures are called macroprudential, although their effect is mainly on the housing sector, and not directly on interactions within the financial system. But they nonetheless deserve being called macroprudential, because the real estate sector is often the source of financial crises, and deploying these measures should reduce the probability of a real estate bubble and its subsequent bursting, which would likely have macroeconomic effects.

And real effects- there would have been more houses built. The political decision is the desire for real housing construction.

The need for surveillance of the financial system as a whole has in some countries led to the establishment of a coordinating committee of regulators. In the United States, that group is the FSOC (Financial Stability Oversight Council), which is chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury. In the United Kingdom, a Financial Policy Committee, charged with the responsibility for oversight of the financial system, has been set up and placed in the Bank of England. It operates under the chairmanship of the Governor of the Bank of England, with a structure similar but not identical to the Bank of Englands Monetary Policy Committee.

Lesson 7: The best time to deal with moral hazard is in designing the system, not in the midst of a crisis.

Agreed!

Moral hazard is about the future course of events.

At the start of the Korean crisis at the end of 1997, critics including friends of mine told the IMF that it would be a mistake to enter a program with Korea, since this would increase moral hazard. I was not convinced by their argument, which at its simplest could be expressed as You should force Korea into a greater economic crisis than is necessary, in order to teach them a lesson. The issue is Who is them? It was probably not the 46 million people living in South Korea at the time. It probably was the policy-makers in Korea, and it certainly was the bankers and others who had invested in South Korea. The calculus of adding to the woes of a country already going through a traumatic experience, in order to teach policymakers, bankers and investors a lesson, did not convince the IMF, rightly so to my mind.

Agreed!

Nor did they need an IMF program!

But the question then arises: Can you ever deal with moral hazard? The answer is yes, by building a system that will as far as possible enable policymakers to deal with crises in a way that does not create moral hazard in future crisis situations. That is the goal of financial sector reforms now underway to create mechanisms and institutions that will put an end to too big to fail.

There was no too big to fail moral hazard issue. The US banks did fail when shareholders lost their capital. Failure means the owners lose and are financially punished, and new owners with new capital have a go at it.

Lesson 8: Dont overestimate the benefits of waiting for the situation to clarify.

Early in my term as Governor of the Bank of Israel, when the interest rate decision was made by the Governor alone, I faced a very difficult decision on the interest rate. I told the advisory group with whom I was sitting that my decision was to keep the interest rate unchanged and wait for the next monthly decision, when the situation would have clarified. The then Deputy Governor, Dr. Meir Sokoler, commented: It is never clear next time; it is just unclear in a different way. I cannot help but think of this as the Tolstoy rule, from the first sentence of Anna Karenina, every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

It is not literally true that all interest rate decisions are equally difficult, but it is true that we tend to underestimate the lags in receiving information and the lags with which policy decisions affect the economy. Those lags led me to try to make decisions as early as possible, even if that meant that there was more uncertainty about the correctness of the decision than would have been appropriate had the lags been absent.

The lesson is to be aggressive with fiscal adjustments when unemployment/the output gap starts to rise as the costs of waiting- massive quantities of lost output and negative externalities, particularly with regard to the lives of those punished by the government allowing aggregate demand to decline- are far higher than, worst case, a period of ‘excess demand’ that can also readily be addressed with fiscal policy.

Lesson 9: Never forget the eternal verities lessons from the IMF. A country that manages itself well in normal times is likely to be better equipped to deal with the consequences of a crisis, and likely to emerge from it at lower cost.

Thus, we should continue to believe in the good housekeeping rules that the IMF has tirelessly promoted. In normal times countries should maintain fiscal discipline and monetary and financial stability. At all times they should take into account the need to follow sustainable growth-promoting macro- and structural policies. And they need to have a decent regard for the welfare of all segments of society.

Yes, at all times they should sustain full employment policy as the real losses from anything less far exceed any other possible benefits.

The list is easy to make. It is more difficult to fill in the details, to decide what policies to

follow in practice. And it may be very difficult to implement such measures, particularly when times are good and when populist pressures are likely to be strong. But a country that does not do so is likely to pay a very high price.

Lesson 10.

In a crisis, central bankers will often find themselves deciding to implement policy actions they never thought they would have to undertake and these are frequently policy actions that they would have preferred not to have to undertake. Hence, a few final words of advice to central bankers (and to others):

Lesson for all bankers:

Proposals for the Banking System, Treasury, Fed, and FDIC

Never say never

II. The Wisdom of My Teachers

:(

Feel free to distribute, thanks.

Over the years, I have found myself remembering and repeating words of advice that I first heard from my teachers, both academics and policymakers. Herewith a selection:

1. Paul Samuelson on econometric models: I would rather have Bob Solow than an econometric model, but Id rather have Bob Solow with an econometric model than Bob Solow without one.

2. Herb Stein: (a) After listening to my long description of what was happening in the Israeli economy in 1985: Yes, but what do we want them to do?”

(b) The difference between a growth rate of 2% and a growth rate of 3% is 50%.

(c) If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

3. Michel Camdessus (former head of the IMF):

(a) At 7 a.m., in his office, on the morning that the U.S. government turned to the IMF to raise $20 billion by 9:30 a.m: Gentlemen, this is a crisis, and in a crisis you do not panic

(b) When the IMF was under attack from politicians or the media, in response to my asking Michel, what should we do?, his inevitable answer was We must do our job.

(c) His response when I told him (his official title was Managing Director of the IMF) that life would be much easier for all of us if he would only get himself a cell phone: Cell phones are for deputy managing directors.

(d) On delegation: In August, when he was in France and I was acting head of the IMF in Washington, and had called him to explain a particularly knotty problem and ask him for a decision, You have more information than me, you decide.

4. George Shultz: This event happened in May 1985, just before Herb Stein and I were due to leave for Israel to negotiate an economic program which the United States would support with a grant of $1.5 billion. I was a professor at MIT, and living in the Boston area. Herb and I spoke on the phone about the fact that we had no authorization to impose any conditions on the receipt of the money. Herb, who lived in Washington, volunteered to talk to the Secretary of State to ask him for authorization to impose conditions. He called me after his meeting and said that the Secretary of State was not willing to impose any conditions on the aid.

We agreed this was a problem and he said to me, Why dont you try. A meeting was hastily arranged and next morning I arrived at the Secretary of States office, all ready to deliver a convincing speech to him about the necessity of conditionality. He didnt give me a chance to say a word. You want me to impose conditions on Israel? I said yes. He said I wont. I asked why not. He said Because the Congress will give them the money even if they dont carry out the program and I do not make threats that I cannot carry out.

This was convincing, and an extraordinarily important lesson. But it left the negotiating team with a problem. So I said, That is very awkward. Were going to say To stabilize the economy you need to do the following list of things. And they will be asking themselves, and if we dont? Is there anything we can say to them?

The Secretary of State thought for a while and said: You can tell them that if they do not carry out the program, I will be very disappointed.

We used that line repeatedly. The program was carried out and the program succeeded.

Thank you all very much.

[1] Council on Foreign Relations. These remarks were prepared for presentation on receipt of the SIEPR (Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research) Prize at Stanford University on March 14, 2014. The Prize is awarded for lifetime contributions to economic policy. I am grateful to Dinah Walker of the Council on Foreign Relations for her assistance.

[2] I draw here on two papers I wrote based on my experience in the IMF: Ten Tentative Conclusions from the Past Three Years, presented at the annual meeting of the Trilateral Commission in 1999, in Washington, DC; and the Robbins Lectures, The International Financial System: Crises and Reform Several other policy-related papers from that period appear in my book: IMF Essays from a Time of Crisis (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004). For the period of the Great Recession, I draw on Central bank lessons from the global crisis, which I presented at a conference on Lessons of the Global Crisis at the Bank of Israel in 2011.

[3] This point was made in my 1999 statement Ten Tentative Conclusions referred to above, and has of course received a great deal of focus in analyses of the Great Recession.

[4] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is Different, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2009.