After the speech, crude up $1.61 and back over $100.

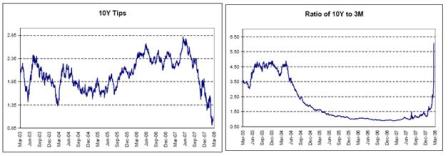

Yields down on fixed income as markets anticipate Fed won’t respond to inflation anytime soon:

February 26, 2008

The U.S. Economy and Monetary Policy

(SNIP)

Several major developments are shaping current economic performance, the outlook, and the conduct of monetary policy. The most prominent of these developments is the contraction in the housing market that began in early 2006. Both the prices and pace of construction of new homes rose to unsustainable levels in the preceding few years. For a time, the resulting correction was largely confined to the housing market, but the consequences of that correction have spread to other sectors of the economy.

The financial markets are playing a key role in the transmission of the housing downturn to the rest of the economy.

(SNIP)

The result has been a substantial tightening in credit availability for many firms and households.

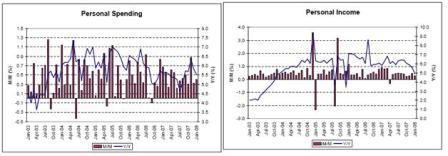

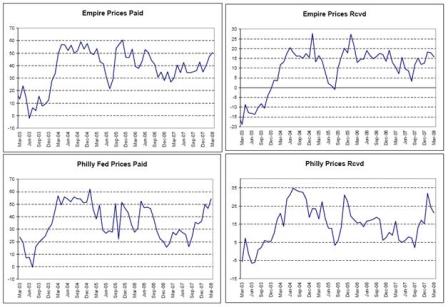

At the same time, continued sizable increases in the prices of food, energy, and other commodities have raised inflation. To some extent, those increases have resulted from strong demand in rapidly growing emerging-market economies, like China and India. But the increases likely also reflect conditions such as adverse weather in some parts of the world, the use of agricultural commodities to produce energy, and geopolitical developments that threaten supplies in some petroleum-producing centers. The higher prices have eroded the purchasing power of household income, adding to restraint on spending.

(SNIP)

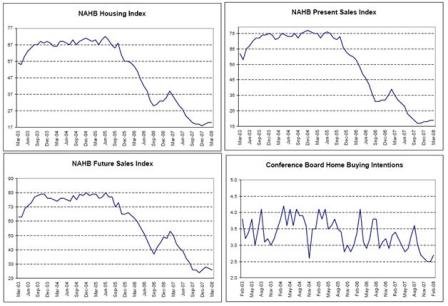

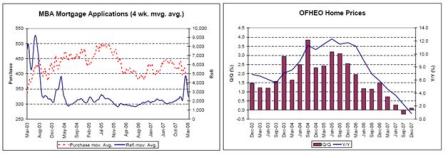

Recent Economic and Financial Developments

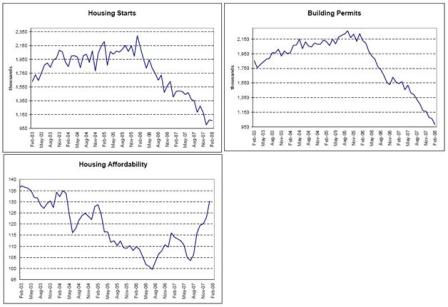

The pace of real economic activity stepped down sharply toward the end of last year and has remained sluggish in recent months. Real gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to have risen only slightly in the fourth quarter. The contraction in the housing market continues to drag down economic growth. Declines in real residential investment subtracted nearly 1 percentage point from the overall increase in real GDP in 2007. Even so, the inventory of unsold new homes remains unusually high, because the demand for housing has fallen about as rapidly as the supply. Problems in the subprime market have virtually cut off financing in this sector. Prime jumbo mortgages are being made, but the lack of a secondary market has caused the spread between rates on these mortgages and on those that have been eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to widen substantially. Even the standards for conforming mortgages have been tightened of late. Weak demand, in turn, is leading to widespread declines in the actual and expected prices of houses, further discouraging buyers. Starts of new single-family homes continued to fall in January, dropping to fewer than 750,000 units–a level of activity more than 1 million units below the peak in early 2006. Judging from the further decline in permits last month, additional cutbacks in construction are likely. It appears that the correction in the housing market has further to go.

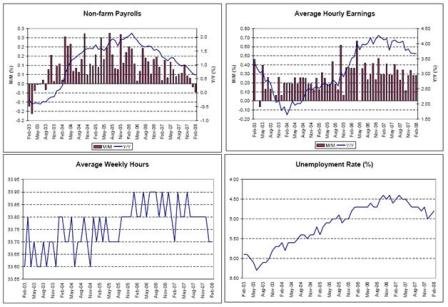

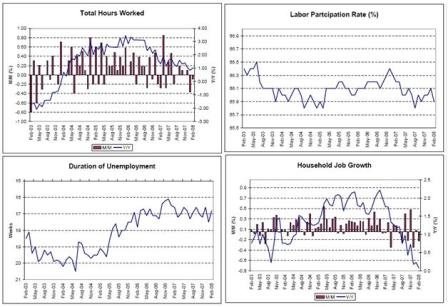

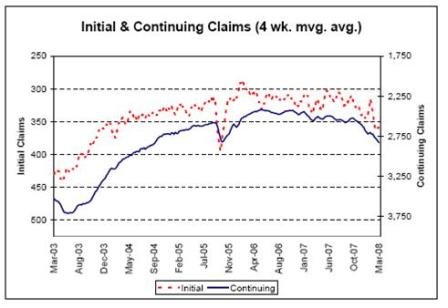

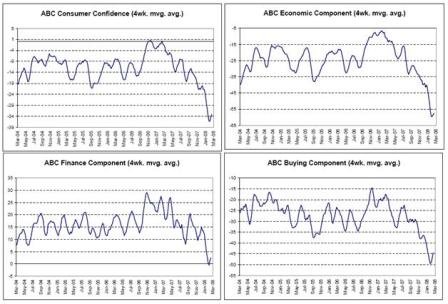

For the better part of the past two years, the trouble in the housing market was contained; however, over the past several months, the weakness appears to have spread to other sectors of the economy. Tighter credit, reductions in housing and equity wealth, higher energy prices, and uncertainty about economic prospects seem to be weighing on business and household spending. Labor demand has softened in recent months. Private nonfarm payrolls were little changed in January, and the unemployment rate moved up to 4.9 percent, on average, during December and January, after remaining around 4-1/2 percent from late 2006 through most of 2007. The higher level of weekly claims for unemployment insurance suggests continued softness in employment this month.

Agreed, the economy has hit the ‘soft spot’ previously forecast by the Fed and private economists.

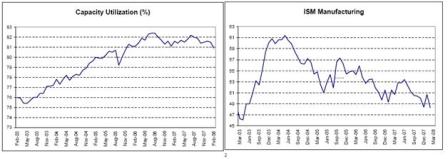

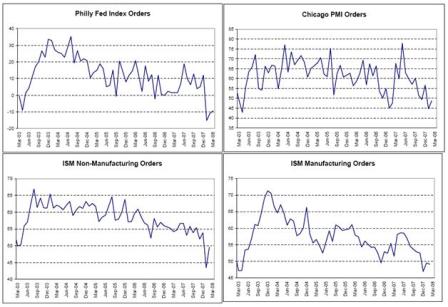

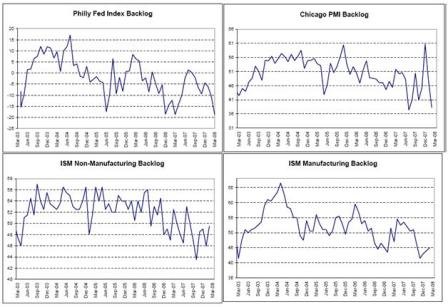

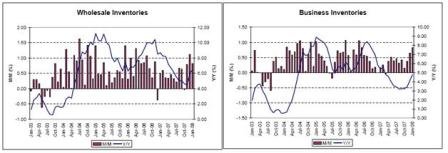

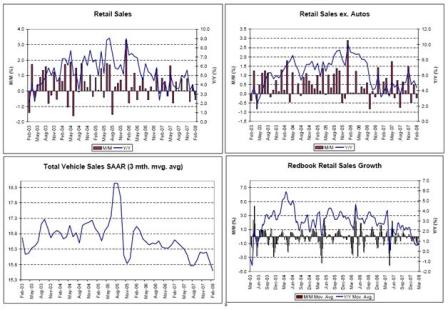

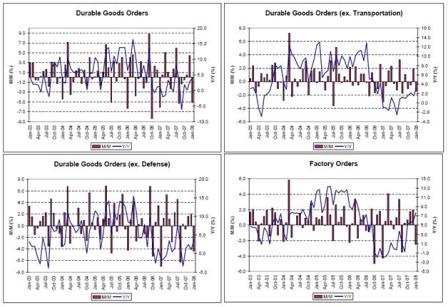

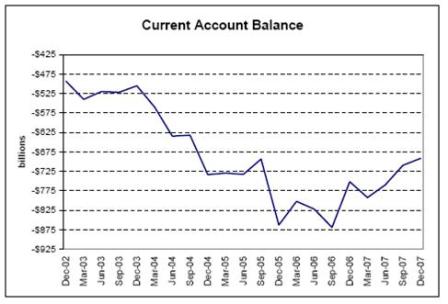

Apart from the labor market, the hard data on economic activity in the first quarter are limited, but, on the whole, the data suggest economic activity has remained very sluggish. Retail sales were up moderately in nominal terms in January, but after adjusting for the rise in prices of consumer goods, real spending on non-auto goods appears to have been little changed last month. In addition, unit sales of new motor vehicles weakened. Total industrial production rose just 0.1 percent in January for a second consecutive month, and manufacturing output was unchanged. Much of the other information about the current quarter has come in the form of surveys of business and consumers–and most all of it has been downbeat. That said, I can still see a few bright spots. One is that the level of business inventories does not appear worrisome at present. Another is that international trade continued to be a solid source of support for the economy through the end of last year. The worsening financial conditions and slower growth in the United States have had some effect on the rest of the world, but the prospects for foreign growth remain favorable.

Agreed, weak domestic demand supported by rising exports.

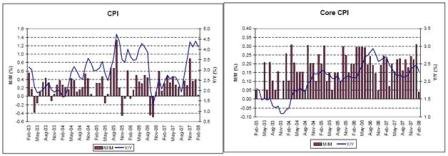

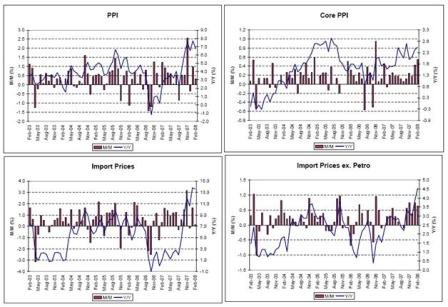

The most recent news on inflation–the January report on the consumer price index (CPI)–was disappointing. Once again, total or headline CPI was boosted by a jump in energy prices and relatively large increases in food prices; last month’s rise left the twelve-month change in the overall CPI at 4.3 percent–twice the pace a year ago. In addition, the January increase of 0.3 percent in the CPI excluding food and energy was slightly higher than the average monthly rate in 2007. Nonetheless, the twelve-month change in this measure of core inflation, at 2-1/2 percent, was still slightly below the rate one year earlier. The recent readings on core inflation suggest that the higher costs of energy, a pickup in prices of imported goods, and, perhaps, the persistent upward price pressures in commodity markets may be passing through a bit to core consumer prices.

Headline passing through to core – not good.

The Implications of Financial Stress for the Economic Outlook

(SNIP)

The pressures from the financial turmoil have been most intense for those financial intermediaries that have been exposed to losses on mortgages and other credits that are repricing, as well as for those institutions now required to bring onto their balance sheets loans that previously would have been sold into securities markets. As those intermediaries take steps to protect themselves from further losses and conserve capital, and as investors more broadly have responded to the evolving risks, spreads on household and business debt in securities markets have widened, the availability of bank credit has decreased, and equity prices have weakened.

In addition to the drying up of large portions of mortgage finance that I referred to previously, conditions have firmed on loans for a variety of other purposes. Responses to our Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey in January showed that banks have tightened terms and standards for household and commercial mortgages, commercial and industrial loans, and consumer loans.

The Fed puts a lot of weight on this and reads it differently than I do. Yes, they have tightened standards, but that doesn’t mean those who had previously qualified no longer qualified under the new standards. For example, requiring a larger down payment is considered tightening, and there’s no evidence yet that would be borrowers don’t simply put more money down. Same with other ‘tightening standards’ issues.

In corporate bond markets, spreads have been widening on both investment- and speculative-grade issues. Lenders are demanding much higher risk premiums for commercial real estate loans. And equity prices have fallen substantially over the past seven months, reducing household wealth and increasing the cost of raising equity capital for businesses.

All true, but part of the great repricing of risk. Arguably spreads were unsustainably narrow a year ago.

To be sure, the easing of monetary policy that I will be discussing in a minute has, quite deliberately, been intended to offset the effect of this tightening, resulting in some borrowers seeing lower interest rates. But financing costs have risen, on balance, for riskier credits, and almost all borrowers are dealing with more cautious lenders who have adopted more stringent standards. Those financial market developments are, in many respects, a healthy correction to previous excesses.

Yes, agreed with that.

But, in some cases, they may represent an overreaction, or at least positioning for the small probability of very adverse economic conditions. In any case, they have the potential to adversely affect household and business spending.

Yes, they have that potential. And regulatory over reach is also a problem he doesn’t address, as the OCC is unnecessarily making things more difficult for small banks to function ‘normally’.

The recovery in financial markets is likely to be a prolonged process. The length of the recuperation will depend importantly on the course of the economy, particularly on developments in the housing market. If the deterioration in the housing market were greater than expected in coming months, the losses borne by financial institutions would be even greater, and lenders might further reduce credit availability. More widespread macroeconomic weakness could make lenders more cautious and could cause the financial problems to spread further. The recent problems of financial guarantors, with possible implications for municipal bond markets as well as for bank balance sheets, are an indication that the financial sector remains vulnerable.

Agreed that parts of the financial sector remains vulnerable, while others are doing exceptionally well.

Even in a more favorable economic environment, some time is likely to be required to restore the functioning and liquidity of a number of markets.

(SNIP)

The Monetary Policy Response

(SNIP)

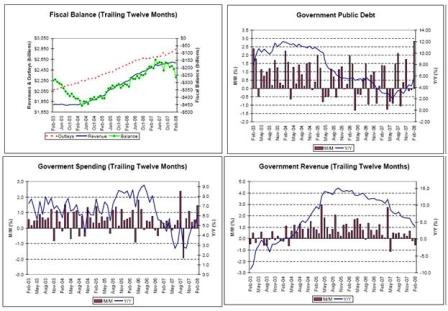

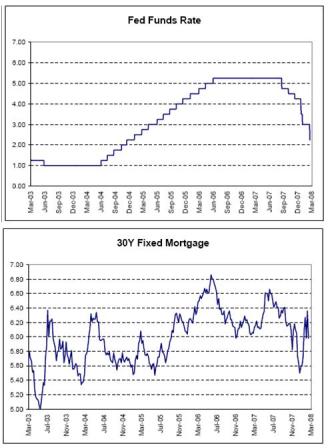

As the deterioration in financial markets increasingly has threatened to hold down spending and employment, the FOMC has eased monetary policy, reducing the federal funds rate target by 2-1/4 percentage points since the turmoil erupted in August. Those actions have been intended to counteract the effects on the overall economy of tighter terms and conditions in credit markets, the drop in equity and housing wealth, and the steep decline in housing activity. Our objective has been to promote sustainable growth and maximum employment over time.

(SNIPS BELOW)

What policy can do is attempt to limit the fallout on the economy from this adjustment.

Lower interest rates should support aggregate demand over time, even in the face of widespread contraction in the supply of credit.

Among other things, lower rates should facilitate the refinancing of mortgage loans, and they will hold down the cost of capital to business.

Easier policy should also support asset prices–or at least cushion declines that otherwise would have occurred.

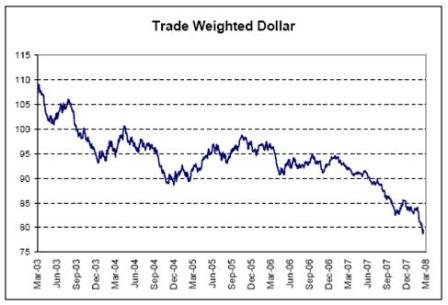

And expected policy easing likely contributed to the drop in the foreign exchange value of the dollar, which is bolstering our exports.

Yes, the ‘inflate your way out of debt’ approach. Highly unusual for a central bank to aggressively do this. Harks back to the ‘beggar thy neighbor’ policies of the 1930s.

The extent of the financial adjustment, as I mentioned previously, is itself highly dependent on how housing and the economy evolve. Part of the rise in risk spreads, reduction in credit availability, and the declines in stock prices in the past few months reflect investor efforts to protect themselves against the potential for very adverse economic outcomes–that is, the exposures and losses that would accompany a persistent steep decline in house prices and a significant recession. Of course, these actions–reducing exposures, tightening credit standards, demanding extra compensation for taking risk–themselves make these “tail risk” scenarios even more likely. In circumstances like these, the decisions of policymakers must take account of not only the most likely course of the economy, but also the possibility of very unfavorable developments.

Not including inflation?

Doing so should reduce the odds on an especially adverse outcome not only by having policy a little easier than otherwise, but also by reassuring lenders and spenders that the central bank recognizes such a possibility in its policy deliberations. Whether the Federal Reserve has done enough in this regard is a question this policymaker will be weighing carefully over coming months.

Even as we respond to forces currently weighing on real activity, we must also set policy to resist any tendency for inflation to increase on a sustained basis. Allowing elevated rates of inflation to become entrenched in inflation expectations would be costly to reverse, constrain our ability to cushion further downward shocks to spending, and result over time in lower and less stable economic expansion. Inflation expectations generally have appeared reasonably well anchored, giving the FOMC room to focus on supporting economic growth. Moreover, as I will explain below, for a variety of reasons, I do not expect the recent elevated inflation rates to persist. In my view, the adverse dynamics of the financial markets and the economy have presented the greater threat to economic welfare in the United States. But the recent information on prices underlines the need to continue to monitor the inflation situation very carefully.

The Outlook for Economic Activity and Inflation

How long the adjustment in financial markets will take and the consequences of that adjustment for economic activity are subject to considerable uncertainty. In my view, the most likely scenario is one in which the economy experiences a period of sluggish growth in demand and production in the near term that is accompanied by some further increase in joblessness.

New building activity will continue to decline until the overhang of inventories of unsold homes has been substantially reduced, and the demand side of the market is not likely to revive appreciably until buyers sense that price declines are abating and financing conditions for mortgages are improving. Consumer spending will be damped by the effects on real incomes of a weak labor market and rising energy prices and by the effects of declines in the stock market and home prices on household wealth. Business spending on capital equipment should be held down by slower sales and production and by caution in a very uncertain economic environment. Nonresidential construction is likely to lose some momentum in the wake of both weak growth in overall economic activity and tighter credit. Some modest offset to these areas of weakness should come from export demand, which should be boosted by the lagged effects of recent declines in the dollar and supported by still-solid growth abroad.

Seems he doesn’t realize export demand is part of the cause of higher prices, as non-residents compete with residents to buy the US output of goods and services. That’s what an export economy looks like, and this will continue for as long as non-resident desires to accumulate $US financial assets continues to fall.

By midyear, economic activity should begin to benefit from several factors. One is the fiscal stimulus package that the Congress recently enacted. The rebates that households are scheduled to begin to receive in May should provide a temporary boost to consumption. Although the timing and the magnitude of the spending response is uncertain, economic studies of the previous experience suggest that a noticeable proportion of households are quite sensitive to temporary cash flow. The potential effects of the business incentives are perhaps more uncertain. Although economic theory suggests that they should bring forward some capital spending, past experience has been mixed.

Second, the decline in residential investment should begin to abate later this year as the overhang of unsold homes is worked off, reducing what has been a significant drag on economic growth over the past two years. Finally, the declines in interest rates that began last summer should be supporting activity over coming quarters, and their effects should show through more clearly to improvements in economic activity as the stress in financial markets dissipates.

Although a firming in the growth of economic activity after midyear now appears the most likely scenario, the outlook is subject to a number of important risks. Further substantial declines in house prices could cut more deeply into household wealth and intensify the problems in mortgage markets and for those intermediaries holding mortgage loans. Financial markets could remain quite fragile, delaying the restoration of more normal credit flows. As observed in the minutes of its most recent meeting, the FOMC has expressed a broad concern about the possibility of adverse interactions among weaker economic activity, stress in financial markets, and credit constraints.

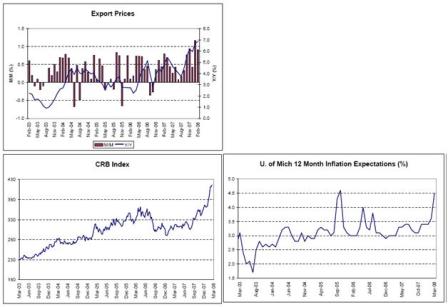

I expect the run-up in headline inflation to be reversed and core inflation to edge lower over the next few years. This projection assumes that energy and other commodity prices will level out, as suggested by the futures markets.

No other reasons? Not much to bet the ranch on? And futures prices for non perishables are not about expectations, but about inventory conditions. Contango indicates a surplus of desired spot inventories and backwardation a shortage of desired spot inventories.

The current backwardated term structure of oil and other futures is indicating shortages, which, if anything, tell me the risk is more to the upside than the downside, as well as support my position that the Saudis/Russians are acting as swing producers and setting price.

Moreover, greater slack in the economy should reduce pressure on prices and wages.

Maybe, but also a risky stance.

Rising import prices are in fact rising real wages for US, as many imports have high labor contents.

And given rising import prices of labor intensive goods and services due to the weak $, lower US domestic real wages shift production back to domestic firms, who support US nominal wages and keep employment firmer than otherwise.

Despite high resource utilization over the past couple of years and periods of elevated headline inflation, labor cost increases have remained quite moderate, and inflation expectations remain reasonably well anchored.

As above, rising import prices represent rising labor costs, and inflation expectations have dropped to only ‘reasonably’ well anchored.

Nonetheless, policymakers must remain very attentive to the outlook for inflation. As I mentioned earlier, the recent uptick in core inflation may reflect some spillover of the higher costs of food, energy, and imports into core prices.

To the mainstream economists, this is a serious development.

And the prices of crude oil and other commodities have moved up further in recent weeks. A related concern is that inflation expectations might drift higher if the current rapid rates of headline inflation persist for longer than anticipated or if the recent easing in monetary policy is misinterpreted as reflecting less resolve among Committee members to maintain low and stable inflation over the medium run. Persistent elevated inflation would undermine the performance of the economy over time.

Worse, to a mainstream economist, including Governor Kohn, it’s a necessary condition for optimal growth and employment.

Conclusion

These have been difficult times for the U.S. economy. The correction of excesses in sectors of the economy and financial markets has spilled over more broadly. Growth has slowed, and unemployment has increased; both borrowers and lenders are facing problems, and the functioning of the financial markets has been disrupted. At the same time, inflation has risen.

Yes, weakness and higher prices.

I believe we will see a return to stronger growth, lower unemployment, lower inflation and improved flows in financial markets, but it probably will take a little while.

This ‘belief’ is at best scantily supported in this speech. Lower inflation because futures are lower? Lower employment/output gap and bringing inflation down to comfort zone at the same time?

And adverse risks to this most likely scenario abound: Uncertainty could trigger an even greater withdrawal from risk-taking by households, businesses, and investors, resulting in more pronounced and prolonged economic weakness; events beyond our borders could continue to put upward pressure on inflation rates.

Yes.

But we should not lose sight of some fundamental strengths of our economy. Our markets have proven to be flexible and resilient, able to absorb shocks, and quick to adapt to changing circumstances. Those markets reward entrepreneurship and risk-taking, and many people are looking for opportunities to buy distressed assets and restructure and strengthen businesses to take advantage of the economic rebound that will occur. Monetary policy has proven itself, under a wide variety of circumstances, very effective in recent decades in damping inflation when needed

Yes, but only by hiking rates. There is no other policy option for bringing down inflation.

and in stimulating demand and activity when that has been appropriate. Our job at the Federal Reserve is to put in place those policies that will promote both price stability and growth over time. We have the tools.

They have one tool – setting the interbank interest rates and other rates as desired.

They have no way of directly increasing or decreasing aggregate demand. That requires direct buying or selling of actual goods and services, not just financial assets.

Treasury spending/taxing directly add/removes demand.

As Chairman Bernanke often emphasizes: We will do what is needed.

Yes, to the best of their knowledge and ability.

This is a relatively neutral speech with more inflation talk than in previous, dovish speeches.

Conclusion:

High February CPI numbers before the next meeting will make it very difficult for the FOMC to vote on a cut without a more than anticipated decline of economic activity.