This is from the same Ben S. Bernanke that stated the Fed spends by using their computer to mark up numbers in bank accounts.

Now, by extension, he’d propose basketball stadiums have a reserve of points for their scoreboards to make sure the teams could get their scores when they put the ball through the hoop.

If he was a state Governor this would be a pretty good speech. But he’s not.

Comments below:

At the Annual Conference of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Washington, D.C.

June 14, 2011

Fiscal Sustainability

I am pleased to speak to a group that has such a distinguished record of identifying crucial issues related to the federal budget and working toward bipartisan solutions to our nation’s fiscal problems.

Yes, we now have bipartisan support for deficit reduction. Good luck to us.

Today I will briefly discuss the fiscal challenges the nation faces and the importance of meeting those challenges for our collective economic future. I will then conclude with some thoughts on the way forward.

Fiscal Policy Challenges

At about 9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), the federal budget deficit has widened appreciably since the onset of the recent recession in December 2007. The exceptional increase in the deficit has mostly reflected the automatic cyclical response of revenues and spending to a weak economy as well as the fiscal actions taken to ease the recession and aid the recovery. As the economy continues to expand and stimulus policies are phased out, the budget deficit should narrow over the next few years.

Both the Congressional Budget Office and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget project that the budget deficit will be almost 5 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2015, assuming that current budget policies are extended and the economy is then close to full employment.1 Of even greater concern is that longer-run projections that extrapolate current policies and make plausible assumptions about the future evolution of the economy show the structural budget gap increasing significantly further over time. For example, under the alternative fiscal scenario developed by the Congressional Budget Office, which assumes most current policies are extended, the deficit is projected to be about 6-1/2 percent of GDP in 2020 and almost 13 percent of GDP in 2030. The ratio of outstanding federal debt to GDP, expected to be about 69 percent at the end of this fiscal year, would under that scenario rise to 87 percent in 2020 and 146 percent in 2030.2 One reason the debt is projected to increase so quickly is that the larger the debt outstanding, the greater the budgetary cost of making the required interest payments. This dynamic is clearly unsustainable.

Unfortunately, even after economic conditions have returned to normal, the nation faces a sizable structural budget gap.

The nation’s long-term fiscal imbalances did not emerge overnight. To a significant extent, they are the result of an aging population and fast-rising health-care costs, both of which have been predicted for decades. The Congressional Budget Office projects that net federal outlays for health-care entitlements–which were 5 percent of GDP in 2010–could rise to more than 8 percent of GDP by 2030. Even though projected fiscal imbalances associated with the Social Security system are smaller than those for federal health programs, they are still significant. Although we have been warned about such developments for many years, the difference is that today those projections are becoming reality.

Up to hear he’s discussed the size of the debt with words like ‘unfortunate’ and ‘imbalances’ and finally we here why he believes this is all a bad thing:

A large and increasing level of government debt relative to national income risks serious economic consequences. Over the longer term, rising federal debt crowds out private capital formation and thus reduces productivity growth.

What? Yes, public acquisition of real goods and services removes those goods and services from the private sector. But this is nothing about that. This is about deficits reducing the ability of firms to raise financial capital to invest in real investment goods and services to keep up productivity.

The type of crowding out the chairman is warning about is part of loanable funds theory, which is applicable to fixed exchange rate regimes, not floating fx regimes. This is a very serious error.

To the extent that increasing debt is financed by borrowing from abroad, a growing share of our future income would be devoted to interest payments on foreign-held federal debt.

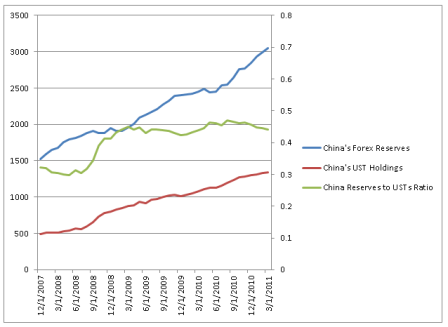

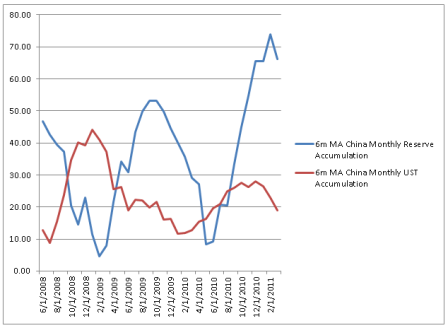

Yes, if the interest payments set by the Fed are high enough, that will happen. However it isn’t necessarily a problem, particularly with the foreign sector’s near 0% propensity to spend their interest income on real goods and services. Japan, for example, as yet to spend a dime of it’s over $1 trillion in dollar holdings accumulated over the last six decades, and china’s holdings only seem to grow as well. In fact, the only way paying interest on the debt could be a problem is if that interest income is subsequently spent in a way we don’t approve of, and it’s easy enough to cross that bridge when we come to it.

High levels of debt also impair the ability of policymakers to respond effectively to future economic shocks and other adverse events.

There is no actual, operational impairment to spend whatever they want whenever they want. Federal spending is not constrained by revenues, as a simple fact of monetary operations. The only nominal constraints on spending are political, and the only constraints on what can be bought are what is offered for sale.

Even the prospect of unsustainable deficits has costs, including an increased possibility of a sudden fiscal crisis.

Where does this come from??? Surely he’s not comparing the US govt, the issuer of the dollar, where he spends by using his computer to mark up numbers in bank accounts, to Greece, a user of the euro, that doesn’t ‘clear its own checks’ like the ECB and the Fed do?

As we have seen in a number of countries recently, interest rates can soar quickly if investors lose confidence in the ability of a government to manage its fiscal policy.

He is looking at Greece!

Although historical experience and economic theory do not show the exact threshold at which the perceived risks associated with the U.S. public debt would increase markedly, we can be sure that, without corrective action, our fiscal trajectory is moving the nation ever closer to that point.

‘That point’ applies to users of a currency, like Greece, the other euro members, US states, businesses, households, etc.

But it does not apply to issuers of their own currency, like the US, Japan, UK, etc.

Is it possible the Fed chairman does not know this???

Perhaps the most important thing for people to understand about the federal budget is that maintaining the status quo is not an option. Creditors will not lend to a government whose debt, relative to national income, is rising without limit; so, one way or the other, fiscal adjustments sufficient to stabilize the federal budget must occur at some point.

Again with the ‘some point’ thing. There is no ‘some point’ for issuers of their own currency, like Japan, who’s debt to GDP is maybe 200% and 10 year JGB’s are trading at 1.15%.

These adjustments could take place through a careful and deliberative process that weighs priorities and gives individuals and firms adequate time to adjust to changes in government programs and tax policies. Or the needed fiscal adjustments could come as a rapid and much more painful response to a looming or actual fiscal crisis in an environment of rising interest rates, collapsing confidence and asset values, and a slowing economy. The choice is ours to make.

Right, the sky is falling.

Achieving Fiscal Sustainability

As if we didn’t already and automatically have it as the issuer of the currency.

The primary long-term goal for federal budget policy must be achieving fiscal sustainability.

What happened to his dual mandates of low inflation and full employment? That’s just for the Fed, but not for budget policy?

Well, if you believe the sky is falling no telling what your priority would be.

A straightforward way to define fiscal sustainability is as a situation in which the ratio of federal debt to national income is stable or moving down over the longer term.

And what does ‘straightforward’ mean? The math is easy? Is that how to set goals for the nation?

This goal can be attained by bringing spending, excluding interest payments, roughly in line with revenues, or in other words, by approximately balancing the primary budget. Given the sharp run-up in debt over the past few years, it would be reasonable to plan for a period of primary budget surpluses, which would serve eventually to bring the ratio of debt to national income back toward pre-recession levels.

All arbitrary measures not tied down to real world consequences apart from being a defensive move to keep the sky from falling.

Fiscal sustainability is a long-run concept. Achieving fiscal sustainability, therefore, requires a long-run plan, one that reduces deficits over an extended period and that, to the fullest extent possible, is credible, practical, and enforceable. In current circumstances, an advantage of taking a longer-term perspective in forming concrete plans for fiscal consolidation is that policymakers can avoid a sudden fiscal contraction that might put the still-fragile recovery at risk.

A glimmer of hope here where he seems to recognize how fiscal adjustments alter the real economy. Unfortunately, with the sky about to fall, he has more important fish to fry.

At the same time, acting now to put in place a credible plan for reducing future deficits would not only enhance economic performance in the long run,

Right, so govt doesn’t crowd out private capital formation with a floating fx regime…

but could also yield near-term benefits by leading to lower long-term interest rates and increased consumer and business confidence.

Yes, long term rates would likely be lower, because markets, which anticipate Fed rate settings, would believe the economy would be weak for a very long time, and therefore the odds of rate hikes would be lower.

While it is crucial to have a federal budget that is sustainable,

Don’t want to crowd out that private capital that gets borrowed from banks where the causation runs from loans to deposits (there’s no such thing as banks running out of money to lend).

our fiscal policies should also reflect the nation’s priorities by providing the conditions to support ongoing gains in living standards and by striving to be fair both to current and future generations.

Living standards are best supported by full employment policy, which happens to be a Fed mandate, in case he’s forgotten.

Interesting question, does the Fed’s mandate extend to influencing policy through speeches as to what others should do, or is it just a mandate for monetary policy decisions?

In addressing our long-term fiscal challenges, we should reform the government’s tax policies and spending priorities so that they not only reduce the deficit, but also enhance the long-term growth potential of our economy–for example, by increasing incentives to work and to save, by encouraging investment in the skills of our workforce, by stimulating private capital formation, by promoting research and development, and by providing necessary public infrastructure.

Big fat fallacy of composition there. Especially from a Princeton professor who should know better.

We cannot reasonably expect to grow our way out of our fiscal imbalances, but a more productive economy will ease the tradeoffs that we face.

Making Fiscal Plans

It is easy to call for sustainable fiscal policies but much harder to deliver them. The issues are not simply technical; they are also closely tied to our values and priorities as a nation. It is little wonder that the debates have been so intense and progress so difficult to achieve.

Recently, negotiations over our long-run fiscal policies have become tied to the issue of raising the statutory limit for federal debt. I fully understand the desire to use the debt limit deadline to force some necessary and difficult fiscal policy adjustments, but the debt limit is the wrong tool for that important job. Failing to raise the debt ceiling in a timely way would be self-defeating

Maybe, but he’s just guessing.

if the objective is to chart a course toward a better fiscal situation for our nation.

The current level of the debt and near-term borrowing needs reflect spending and revenue choices that have already been approved by the current and previous Congresses and Administrations of both political parties. Failing to raise the debt limit would require the federal government to delay or renege on payments for obligations already entered into. In particular, even a short suspension of payments on principal or interest on the Treasury’s debt obligations could cause severe disruptions in financial markets and the payments system, induce ratings downgrades of U.S. government debt, create fundamental doubts about the creditworthiness of the United States, and damage the special role of the dollar and Treasury securities in global markets in the longer term.

All of which has happened to Japan, with no adverse consequences on the currency or interest rates, as is necessarily the case for the issuer of a non-convertible currency and floating exchange rate.

Interest rates would likely rise, slowing the recovery and, perversely, worsening the deficit problem by increasing required interest payments on the debt for what might well be a protracted period.3

Some have suggested that payments by the Treasury could be prioritized to meet principal and interest payments on debt outstanding, thus avoiding a technical default on federal debt. However, even if that were the case, given the current size of the deficit and the uneven time pattern of government receipts and payments, the Treasury would soon find it necessary to prioritize among and withhold critical disbursements, such as Social Security and Medicare payments and funds for the military.

Yes, as congress is well aware, to the point that it’s no longer about a debt default, but about a partial shutdown of the rest of the govt.

This has been yesterday’s speech. Congress has moved on from the risk of debt default to the risk of partial govt shutdown.

Moreover, while debt-related payments might be met in this scenario, the fact that many other government payments would be delayed could still create serious concerns about the safety of Treasury securities among financial market participants.

That doesn’t follow?

The Hippocratic oath holds that, first, we should do no harm. In debating critical fiscal issues, we should avoid unnecessary actions or threats that risk shaking the confidence of investors in the ability and willingness of the U.S. government to pay its bills.

Our reps take a different oath

In raising this concern, I am by no means recommending delay or inaction in addressing the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges–quite the opposite. I urge the Congress and the Administration to work in good faith to quickly develop and implement a credible plan to achieve long-term sustainability. I hope, though, that such a plan can be achieved in the near term without resorting to brinksmanship or actions that would cast doubt on the creditworthiness of the United States.

What would such a plan look like? Clear metrics are important, together with triggers or other mechanisms to establish the credibility of the plan. For example, policymakers could commit to enacting in the near term a clear and specific plan for stabilizing the ratio of debt to GDP within the next few years and then subsequently setting that ratio on a downward path.

Again, the falling sky trumps concerns over output and employment.

Indeed, such a trajectory for the ratio of debt to GDP is comparable to the one proposed by the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform.4To make the framework more explicit, the President and congressional leadership could agree on a definite timetable for reaching decisions about both shorter-term budget adjustments and longer-term changes. Fiscal policymakers could look now to find substantial savings in the 10-year budget window, enforced by well-designed budget rules, while simultaneously undertaking additional reforms to address the long-term sustainability of entitlement programs.

In other words, cuts in the social security and Medicare budgets. This at a time of record excess capacity.

If only the sky wasn’t falling…

Such a framework could include a commitment to make a down payment on fiscal consolidation by enacting legislation to reduce the structural deficit over the next several years.

Conclusion

The task of developing and implementing sustainable fiscal policies is daunting, and it will involve many agonizing decisions and difficult tradeoffs. But meeting this challenge in a timely manner is crucial for our nation. History makes clear that failure to put our fiscal house in order will erode the vitality of our economy, reduce the standard of living in the United States, and increase the risk of economic and financial instability.

And what history might that be? There’s no such thing as a currency issuer ever not being able to make timely payment.

Madison sq garden will not run out of points to post on the scoreboard.

And check out the references. He relies on the information from the group he’s addressing:

References

Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (2010). The CRFB Medium and Long-Term Baselines. Washington: CRFB, August.

Congressional Budget Office (2010). The Long-Term Budget Outlook. Washington: Congressional Budget Office, June (revised August).

National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform (2010). The Moment of Truth: Report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. Washington: NCFRR, December.

Zivney, Terry L., and Richard D. Marcus (1989). “The Day the United States Defaulted on Treasury Bills,” Financial Review, vol. 24 (August), pp. 475-89.