Payrolls up 243k, better than expected,

however the output gap continues to widen,

as we continue continue to go the way of Japan.

Labor force participation rate, 1978-now:

Payrolls up 243k, better than expected,

however the output gap continues to widen,

as we continue continue to go the way of Japan.

Labor force participation rate, 1978-now:

But their banking system is sound.

Like talking about how good the person looked at his funeral?

Karim writes:

Another downbeat number with the unemployment rate rising to an 8mth high of 7.6% (from 7.5%).

Total employment up 2.3k, with full-time jobs -3.6k after -21.7k the prior month.

In the past 5mths the unemployment rate in Canada has risen by 0.4% while the U.S. has fallen 0.6% (subject to today’s #)-a large move in a short time.

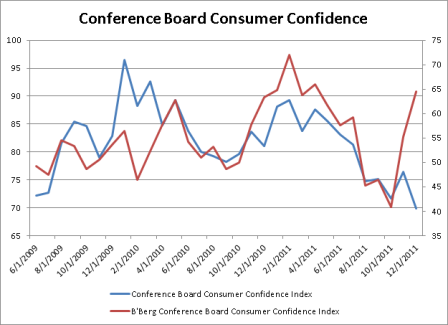

Chart below shows the recent divergence in Conference Board confidence surveys for Canada (blue) and U.S. (red).

I may have mentioned that for the size govt we have we are grossly over taxed?

;)

Real GDP is growing, but weakly compared with the postwar average recovery.

The recovery from the 1980 recession was even weaker at this stage, but that reflected a double-dip recession in 1981.

The economy would have to grow at a 7.6 percent annualized rate in order to catch up with the average postwar recovery by the end of 2012.

The consensus forecast for 2012 growth as reported by Bloomberg is 2.1 percent, up just slightly from a forecast of 2.0 percent as of last October.

Soft home prices have been central to the weakness of the recovery.

The continued weakness of nominal home prices is a postwar anomaly.

In every previous postwar recovery, the stock of household debt has risen as the recovery has begun.

In the current recovery, the collapse in home prices has severely damaged household balance sheets. As a result, consumers have avoided taking on new debt.

The result is weak consumer demand and, hence, a slow recovery.

The slow recovery is obvious in the labor market, where job growth remains painfully sluggish compared to the average recovery.

The recent uptick at the end of the Current Recovery linev(red) is the result of encouraging payroll data announced on January 6th 2012.

Because of the depth of the recent recession, one might expect stronger-than-average improvement in industrial production.

Despite the predicted snapback, the increase in industrial production during this recovery is actually slightly slower than in the average postwar case.

Capacity in manufacturing, mining, and electric and gas utilities usually grows steadily from the start of a recovery.

However, during the current recovery, investment has been so low that capacity is actually declining. Plants and machinery are depreciating faster than they are being installed.

The growth in world trade exceeds even the best postwar experiences.

However, this reflects the depth of the fall during the recession.

The federal deficit since the start of the recovery has been much higher than in previous postwar cases.

Although the deficit has shrunk slightly, its level creates significant challenges for policymakers and the economy.

The traditional American enthusiasm for the road has been dulled by a combination of weak recovery and high fuel prices.

When compared to other postwar recessions, total vehicle miles traveled in this current recovery has not only lagged the average, but has registered no growth whatever.

They don’t need to ‘create jobs’ as there is already more to do than there are people to do it.

They need to remove fiscal drag with tax cuts and/or spending increases to allow the needs to be funded:

Sustained Global Unemployment: Interesting stats from the International Labor Organization noting that there are nearly 200million unemployed globally and that another 40million jobs need to be created each year for the next decade. To generate sustainable growth while maintaining social cohesion the world must create 600million production jobs over the next decade which would still leave 900million workers and their families below the $2 a day poverty line, largely in developing countries. These numbers are fairly sobering when you consider that the world’s largest economy only managed to net create around 1.9million jobs in the recent ‘recovery’ and only around 7 million jobs even during the ‘boom’ years between 2002-2007.

My proposals remain:

1. A full FICA suspension:

The suspension of FICA paid by employees restores spending which supports output and employment.

The suspension of FICA paid by business helps keep costs down which in a competitive environment lowers prices for consumers.

2. $150 billion one time distribution by the federal govt to the states on a per capita basis to get them over the hump.

3. An $8/hr federally funded transition job for anyone willing and able to work to assist in the transition from unemployment to private sector employment.

Call me an inflation hawk if you want. But when the fiscal drag is removed with the FICA suspension and funds for the states I see risk of what will be seen as ‘unwelcome inflation’ causing Congress to put on the brakes long before unemployment gets below 5% without the $8/hr transition job in place, even with the help of the FICA suspension in lowering costs for business.

It’s my take that in an expansion the ’employed labor buffer stock’ created by the $8/hr job offer will prove a superior price anchor to the current practice of using the current unemployment based buffer stock as our price anchor.

The federal government caused this mess for allowing changing credit conditions to cause its resulting over taxation to unemploy a lot more people than the government wanted to employ. So now the corrective policy is to suspend the FICA taxes, give the states the one time assistance they need to get over the hump the federal government policy created, and provide the transition job to help get those people that federal policy is causing to be unemployed back into private sector employment in a more orderly, more ‘non inflationary’ manner.

I’ve noticed the criticism the $8/hr proposal- aka the ‘Job Guarantee’- has been getting in the blogosphere, and it continues to be the case that none of it seems logically consistent to me, as seen from an MMT perspective. It seems the critics haven’t fully grasped the ramifications of the recognition of the currency as a (simple) public monopoly as outlined in Full Employment AND Price Stability and the other mandatory readings.

So yes, we can simply restore aggregate demand with the FICA suspension and funds for the states, but if I were running things I’d include the $8 transition job to improve the odds of both higher levels of real output and lower ‘inflation pressures’.

Also, this is not to say that I don’t support the funding of public infrastructure (broadly defined) for public purpose. In fact, I see that as THE reason for government in the first place, and it should be determined and fully funded as needed. I call that the ‘right size’ government, and, in general, it’s not the place for cyclical adjustments.

4. An energy policy to help keep energy consumption down as we expand GDP, particularly with regard to crude oil products.

Here my presumption is there’s more to life than burning our way to prosperity, with ‘whoever burns the most fuel wins.’

Perhaps more important than what happens if these proposals are followed is what happens if they are not, which is more likely going to be the case.

First, given current credit conditions, world demand, and the 0 rate policy and QE, it looks to me like the current federal deficit isn’t going to be large enough to allow anything better than muddling through we’ve seen over the last few years.

Second, potential volatility is as high as it’s ever been. Europe could muddle through with the ECB doing what it takes at the last minute to prevent a collapse, or doing what it takes proactively, or it could miss a beat and let it all unravel. Oil prices could double near term if Iran cuts production faster than the Saudis can replace it, or prices could collapse in time as production comes online from Iraq, the US, and other places forcing the Saudis to cut to levels where they can’t cut any more, and lose control of prices on the downside.

In other words, the risk of disruption and the range of outcomes remains elevated.

U.K. to Propose Work-for-Benefits Program, Sunday Times Reports

By Svenja O’Donnell

Jan 8 (Bloomberg) — The U.K. coalition government is planning a compulsory community work program for the long-term unemployed, the Sunday Times said, citing Employment Minister Chris Grayling.

The plan will include stopping benefits for as many as three years for those who refuse to sign up, the newspaper said.

Grayling has indicated his support for the plan, saying a “work for dole” program will help curb the U.K.’s expenditure on benefits for the jobless, the paper said.

People who have been unemployed for three years or more will be forced to work unpaid for six months under the terms of the program, the Sunday Times said.

In case you missed this.

From GS:

MAIN POINTS:

1. Nonfarm payroll employment increased by 200k in December, a larger gain than the consensus had expected. Part of the strong gain reflected a 42k increase in employment for “couriers and messengers”, which likely reflects temporary employment for holiday gift delivery persons. A similar spike occurred last December and was reversed in the following month, indicating that the payroll statistics are not properly seasonally adjusting for this type of hiring. Taking this into account, December employment growth was still firmer than the preceding two months, but the underlying trend is likely still below 200k.

Another well stated piece from John Carney on the CNBC website:

Modern Monetary Theory and Austrian Economics

By John Carney

Dec 27 (CNBC) — When I began blogging about Modern Monetary Theory, I knew I risked alienating or at least annoying some of my Austrian Economics friends. The Austrians are a combative lot, used to fighting on the fringes of economic thought for what they see as their overlooked and important insights into the workings of the economy.

Which is one of the things that makes them a lot like the MMT crowd.

There are many other things that Austrian Econ and MMT share. A recent post by Bob Wenzel at Economic Policy Journal, which is presented as a critique of my praise of some aspects of MMT, actually makes this point very well.

The MMTers believe that the modern monetary system—sovereign fiat money, unlinked to any commodity and unpegged to any other currency—that exists in the United States, Canada, Japan, the UK and Australia allows governments to operate without revenue constraints. They can never run out of money because they create the money they spend.

This is not to say that MMTers believe that governments can spend without limit. Governments can overspend in the MMT paradigm and this overspending leads to inflation. Government financial assets may be unlimited but real assets available for purchase—that is, goods and services the economy is capable of producing—are limited. The government can overspend by (a) taking too many goods and services out of the private sector, depriving the private sector of what it needs to satisfy the people, grow the economy and increase productivity or (b) increasing the supply of money in the economy so large that it drives up the prices of goods and services.

As Wenzel points out, Murray Rothbard—one of the most important Austrian Economists the United States has produced—takes exactly the same position. He says that governments take “control of the money supply” when they find that taxation doesn’t produce enough revenue to cover expenditures. In other words, fiat money is how governments escape revenue constraint.

Rothbard considers this counterfeiting, which is a moral judgment that depends on the prior conclusion that fiat money isn’t the moral equivalent of real money. Rothbard is entitled to this view—I probably even share it—but that doesn’t change the fact that in our economy today, this “counterfeiting” is the operational truth of our monetary system. We can decry it—but we might as well also try to understand what it means for us.

Rothbard worries that government control of the money supply will lead to “runaway inflation.” The MMTers tend to be more sanguine about the danger of inflation than Rothbard—although I do not believe they are entitled to this attitude. As I explained in my piece “Monetary Theory, Crony Capitalism and the Tea Party,” the MMTers tend to underestimate the influence of special interests—including government actors and central bankers themselves—on monetary policy. They have monetary policy prescriptions that would avoid runaway inflation but, it seems to me, there is little reason to expect these would ever be followed in the countries that are sovereign currency issuers. I think that on this point, many MMTers confuse analysis of the world as it is with the world as they would like it to be.

In short, the MMTers agree with Rothbard on the purpose and effect of government control of money: it means the government is no longer revenue constrained. They differ about the likelihood of runaway inflation , which is not a difference of principle but a divergence of political prediction.

This point of agreement sets both Austrians and MMTers outside of mainstream economics in precisely the same way. They appreciate that the modern monetary system is very, very different from older, commodity based monetary systems—in a way that many mainstream economists do not.

In MM, CC & TP, I briefly mentioned a few other positions on the economy MMTers tend to share. Wenzel writes that “there is nothing right about these views.”

I don’t think Wenzel actually agrees with himself here. Let’s run through these one by one.

1. The MMTers think the financial system tends toward crisis. Wenzel writes that the financial system doesn’t tend toward crisis. But a moment later he admits that the actual financial system we have does tend toward crisis. All Austrians believe this, as far as I can tell.

What has happened here is that Wenzel is now the one confusing the world as it is with the world as he wishes it would be. Perhaps under some version of the Austrian-optimum financial system—no central bank, gold coin as money, free banking or no fractional reserve banking—we wouldn’t tend toward crisis. But that is not the system we have.

The MMTers aren’t engaged with arguing about the Austrian-optimum financial system. They are engaged in describing the actual financial system we have—which tends toward crisis.

They even agree that the tendency toward crisis is largely caused by the same thing, credit expansions leading to irresponsible lending.

2. The MMTers say that “capitalist economies are not self-regulating.” Again, Wenzel dissents. But if we read “capitalist economies” as “modern economies with central banking and interventionist governments” then the point of disagreement vanishes.

Are we entitled to read “capitalist economies” in this way? I think we are. The MMTers are not, for the most part, attempting to argue with non-existent theoretical economies or describe the epic-era Icelandic political economy. They are dealing with the economy we have, which is usually called “capitalist.” Austrians can argue that this isn’t really capitalism—but this is a terminological quibble. When it comes down to the problem of self-regulation of our so-called capitalist system, the Austrians and MMTers are in agreement.

3. Next up is the MMT view (borrowed from an earlier economic school called “Functional Finance”) that fiscal policy should be judged by its economic effects. Wenzel asks if this means that this “supercedes private property that as long as something is good for the economy, it can be taxed away from the individual?”

Here is a genuine difference between the Austrians—especially those of the Rothbardian stripe—and the MMTers. The MMTers do indeed envision the government using taxes to accomplish what is good for the economy—which, for the most part, means combating inflation. They think that the government may need to use taxation to snuff out inflation at times. Alternatively, the government can also reduce its own spending to extinguish inflation.

Note that we’ve come across a gap between MMTers and Rothbardians that is far smaller than the chasm between either of them and mainstream economics, where taxation of private property and income is regularly seen as justified by the need to fund government operations. MMTers and Austrians both agree that under the current circumstances people in most developed countries are overtaxed.

4. Wenzel actually overlooks the larger gap between Austrians and MMTers, which has to do with the efficacy of government spending. Many MMTers believe that most governments in so-called capitalist economies are not spending enough. Most—if not all—Austrians think that these same government are spending too much.

The Austrian view is based on the idea that government spending tends to distort the economy, in part because—as the MMTers would agree—government spending in our age typically involves monetary expansion. The MMTers, I would argue, have a lot to learn from the Austrians on this point. I think that an MMT effort to more fully engage the Austrians on the topic of the structure of production would be well worth the effort.

5. Wenzel’s challenge to the idea of functional finance is untenable—and not particularly Austrian. He argues that the subjectivity of value means it is impossible for us to tell whether something is “good for the economy.” Humbug. We know that an economy that more fully reflects the aspirations and choices of the individuals it encompasses is better than one that does not. We know that high unemployment is worse than low unemployment. All other things being equal, a more productive economy is superior to a less productive economy, a wealthier economy is better than a more impoverished one.

Wenzel’s position amounts to nihilism. I think he is confusing the theory of subjective value with a deeper relativism. Subjectivism is merely the notion that the value of an economic good—that is, an object or a service—is not inherent to the thing but arises from within the individual’s needs and wants. This does not mean that we cannot say that some economic outcome is better or worse or that certain policy prescription are good for the economy and certain are worse.

It would be odd for any Austrian to adopt the nihilism of Wenzel. It’s pretty rare to ever encounter an Austrian who lacks normative views of the economy. These normative views depend on the view that some things are good for economy and some things are bad. I doubt that Wenzel himself really subscribes to the kind of nihilism he seems to advocate in his post.

Wenzel’s final critique of me is that I over-emphasize cronyism and underplay the deeper problems of centralized power. My reply is three-fold. First, cronyism is a more concrete political problem than centralization; tactically, it makes sense to fight cronyism. Second, cronyism is endemic to centralized government decisions, as the public choice economists have shown. They call it special interest rent-seeking, but that’s egg-head talk from cronyism. Third, I totally agree: centralization is a real problem because the “rationalization” involved necessarily downplays the kinds of unarticulated knowledge that are important to everyday life, prosperity and happiness.

At the level of theory, Austrians and MMTers have a lot in common. Tactically, an alliance makes sense. Intellectually, bringing together the descriptive view of modern monetary systems with Austrian views about the structure of production and limitations of economic planning (as well Rothbardian respect for individual property rights) should be a fruitful project.

So, as I said last time, let’s make it happen.

That includes selling trinkents and services to the higher income foreign tourists and residents. I used to call it Sultan fanning.

It is not a sign of prosperty…

Resurgent self-employment soars to 75-year high

By Richard Tyler

Dec 26 (Telegraph) — Britain is witnessing a renaissance in self-employment on a scale not seen since the 1930s, the latest business figures show.

Barclays estimates that nearly 480,000 new businesses were created over the past year a record and said official statistics revealed that self-employment now stood at the highest level relative to the total working population for 75 years.

The UK is in the middle of a boom for start-ups. Our best guess is that in England and Wales we are up 4pc to 5pc in the year to November and thats on the back of two strong years, said Richard Roberts, small and medium enterprise analyst at Barclays.

He said more people were setting up their own ventures because being self-employed had become more socially accepted.

The enduring nature of the economic downturn was also a factor. Few people will voluntarily risk their savings during short, sharp recessions, Dr Roberts said, with any increase in entrepreneurial activity coming from people shifting from unemployment into self-employment.

As the economy has shown little sign of recovering for the past two years, people were taking the plunge, he said. Most new business owners would have spotted an opportunity to make money, but some will have been made redundant and had no choice.