Because they think they could be the next Greece they *are* Japan.

BOJ’s Shirakawa Says Japan’s Fiscal Situation Is ’Very Severe’

By Mayumi Otsuma

March 23 (Bloomberg) — Bank of Japan Governor Masaaki Shirakawa said that while Japan’s fiscal situation is “very severe,” investors’ trust in the country’s policy makers is keeping bond yields low. He spoke in parliament today in Tokyo.

Japan Mulls Postwar-Style Reconstruction Agency, Adds Cash

By Takashi Hirokawa and Keiko Ujikane

March 23 (Bloomberg) — Japan may set up a reconstruction agency to oversee earthquake repairs, while data showed the central bank pumped record liquidity into lenders, as the nation grappled with its worst disaster since World War II.

Underwriting Bonds

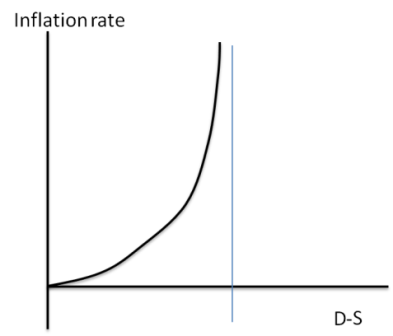

“If a central bank starts to underwrite government bonds, there may be no problems at first, but it would lead to a limitless expansion of currency issuance, spur sharp inflation and yield a big blow to people’s lives and economic activities,” as has happened in the past, Shirakawa said.

By law, the central bank can directly buy JGBs only in extraordinary circumstances with the permission of the Diet. Vice Finance Minister Fumihiko Igarashi said in parliament that the government needed to be “cautious” in considering whether to have the BOJ make direct purchases.

Bond sales, cuts to other spending and tax measures could pay for reconstruction, Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Kaoru Yosano said yesterday. Morgan Stanley MUFG Securities Co. analysts led by Robert Feldman in Tokyo wrote in a note this week that policy makers will likely implement “several” spending packages of 10 trillion yen or more.

Loan Programs

Fiscal spending won’t be the only channel for stimulus, according to Chotaro Morita, chief strategist at Barclays Capital Japan Ltd. in Tokyo.

“We expect the utilization of government lending” vehicles such as the Government Housing Loan Corporation and Finance Corporation for Municipal Governments, as was done in the wake of the 1995 Kobe earthquake, Morita wrote in a report to clients yesterday. This would help reduce the increase in government-bond issuance, he said.

In the wake of the devastation of World War II, Japan’s government set up the Economic Stabilization Board in August 1946. Among its duties was to ration commodities and oversee the revival of the nation’s industries.

To maintain short-term financial stability, BOJ policy makers have added emergency cash every business day since the quake. Lenders’ current-account balances at the central bank yesterday exceeded the 36.4 trillion yen record set in March 2004, when officials were implementing so-called quantitative easing measures to counter deflation. Deposits have climbed from about 17.6 trillion yen on March 10.

Japan Forecasts Earthquake Damage May Swell to $309 Billion

By Keiko Ujikane

March 23 (Bloomberg) — Japan’s government estimated the damage from this month’s record earthquake and tsunami at as much as 25 trillion yen ($309 billion), an amount almost four times the hit imposed by Hurricane Katrina on the U.S.

The destruction will push down gross domestic product by as much as 2.75 trillion yen for the year starting April 1, today’s report showed. The figure, about 0.5 percent of the 530 trillion yen economy, reflects a decline in production from supply disruptions and damage to corporate facilities without taking into account the effects of possible power outages.

The figures are the first gauge of the scale of rebuilding Prime Minister Naoto Kan’s government will face after the quake killed more than 9,000 people. Japan may set up a reconstruction agency to oversee the rebuilding effort and the central bank has injected record cash to stabilize financial markets.

Damages will probably amount to between 16 trillion yen and 25 trillion yen, today’s report said. It covers destruction to infrastructure in seven prefectures affected by the disaster, including damages to nuclear power facilities north of Tokyo.

Wider implications on the economy, including how radiation will affect food and water supply, are not included in the estimate.

Bank of Japan board member Ryuzo Miyao said today that it may take more time to overcome the damage of the quake than it did after the 1995 disaster in Kobe, western Japan.

Power Shortage

Tokyo’s power supply may fall 20,500 megawatts short of summer demand, or 34 percent less than the peak consumption last year, according to figures from Tokyo Electric Power Co. The utility is capable of supplying 37,500-megawatts and plans to add about 2,000 megawatts of thermal generation by the end of this month, company spokesman Naoyuki Matsumoto said by telephone today.

The government had previously projected growth of 1.5 percent for the year starting April 1 after growing an estimated 3.1 percent this year.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch cut its GDP projection for fiscal 2011 to 1 percent from 1.7 percent. RBS Securities and Nomura Securities Co. have also cut their forecasts while noting that the economy will still expand because the rebuilding will spur demand and help offset damage on growth in the period.

Rebuilding efforts in fiscal 2011 could push up GDP by 5 trillion yen to 7.75 trillion yen, the government said today.

Japan’s growth will return to normal “very soon” as reconstruction work starts, Justin Lin, the World Bank’s chief economist, said in Hong Kong today. At the same time, some are worried the boost won’t come soon enough.

Biggest Concern

“My biggest concern is that a positive impact from reconstruction may take a while to materialize,” said Akiyoshi Takumori, chief economist at Sumitomo Mitsui Asset Management Co. in Tokyo. “This earthquake and tsunami destroyed infrastructure and that will delay a recovery in production, a major driving force for the economy.”

The government maintained its assessment of the economy for March as the economic indicators released before the earthquake showed exports and production rebounding, while also voicing “concern” about the impact of the temblor on the economy.

“Although the Japanese economy is turning to pick up, its ability to self-sustain itself is weak,” the Cabinet Office said in a monthly report.

The U.S. National Hurricane Center in August 2006 calculated the damage of Hurricane Katrina, which slammed into New Orleans the year before, at $81 billion.

Future assessments will need to address damage to much of the northeast’s economy, and the disruptions to electricity and distribution systems that’s spread south to Tokyo and beyond.

Toyota Motor Corp. said yesterday it will halt car assembly in Japan through March 26. Sony Corp. said it shut five more plants.

Export Decline

Koji Miyahara, president of the Japanese Shipowners’ Association, said today exports may decline for six to 12 months after the earthquake, adding that the disaster won’t affect the industry in the longer term as reconstruction efforts take hold.

Kan is now faced with the challenge of finding ways to pay for the damage to the economy. BOJ Governor Masaaki Shirakawa has reiterated a reluctance to underwrite debt from the government and said today that nation’s fiscal situation is “very severe.”