There is no right time for the Fed to raise rates!

Introduction

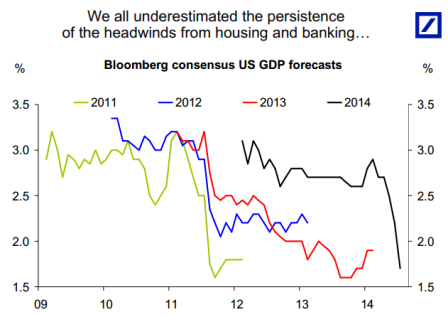

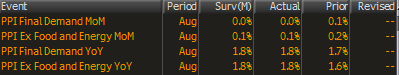

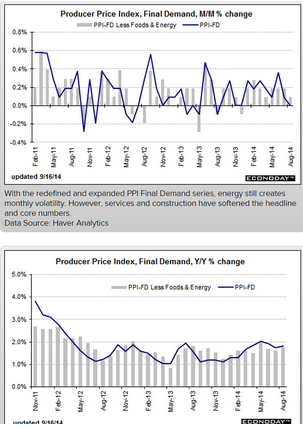

I reject the belief that economy is strong and operating anywhere near full employment. I also reject the belief that a zero-rate policy is inflationary, supports aggregate demand, or weakens the currency, or that higher rates slow the economy and reduce inflation. Additionally, I reject the mainstream view that employment is materially improving, the output gap is closing, and inflation is rising and returning to the Fed’s targets.

What I am asserting is that the Fed and the mainstream have it backwards with regard to how interest rates interact with the economy. They have it backwards with regard to both the current health of the economy and inflation, and, therefore, their discussion of appropriate monetary policy is entirely confused and inapplicable.

Furthermore, while I recognize that raising rates supports both aggregate demand and inflation, I am categorically against raising rates for that purpose. Instead, I propose making the zero-rate policy permanent and supporting demand with a full FICA tax suspension. And for a stronger price anchor than today’s unemployment policy, I propose a federally funded transition job for anyone willing and able to work to facilitate the transition from unemployment to private sector employment. Together these proposals support far higher levels of employment and price stability.

So when is the appropriate time to raise rates? I say never. Instead, leave the fed funds rate at zero, permanently, by law, and use fiscal adjustments to sustain full employment.

Analysis

My first point of contention with the mainstream is their presumption that low rates are supportive of aggregate demand and inflation through a variety of channels, including credit, expectations, and foreign exchange channels.

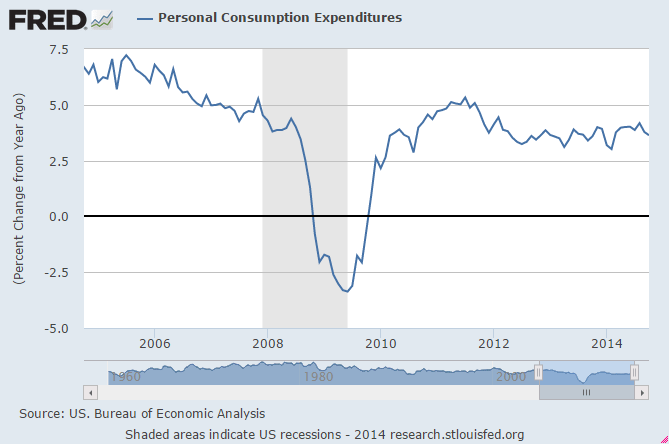

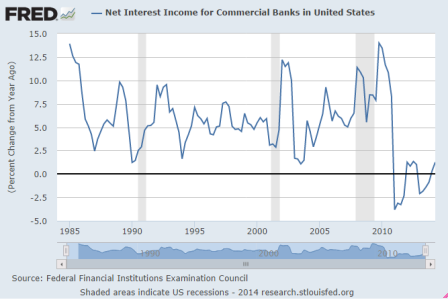

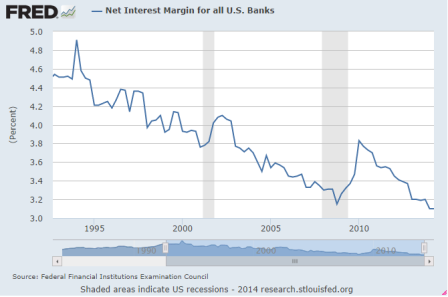

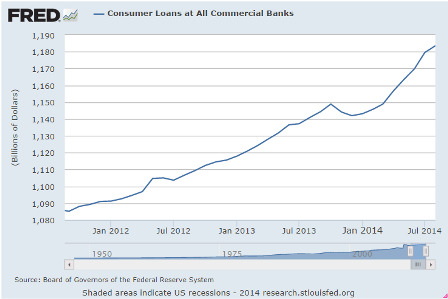

The problem with the mainstream credit channel is that it relies on the assumption that lower rates encourage borrowing to spend. At a micro level this seems plausible- people will borrow more to buy houses and cars, and business will borrow more to invest. But it breaks down at the macro level. For every dollar borrowed there is a dollar saved, so any reduction in interest costs for borrowers corresponds to an identical reduction for savers. The only way a rate cut would result in increased borrowing to spend would be if the propensity to spend of borrowers exceeded that of savers. The economy, however, is a large net saver, as government is an equally large net payer of interest on its outstanding debt. Therefore, rate cuts directly reduce government spending and the economy’s private sector’s net interest income. And looking at over two decades of zero-rates and QE in Japan, 6 years in the US, and 5 years of zero and now negative rates in the EU, the data is also telling me that lowering rates does not support demand, output, employment, or inflation. In fact, the only arguments that they do are counter factual- the economy would have been worse without it- or that it just needs more time. By logical extension, zero-rates and QE have also kept us from being overrun by elephants (not withstanding that they lurk in every room).

The second channel is the inflation expectations channel. This presumes that inflation is caused by inflation expectations, with those expecting higher prices to both accelerate purchases and demanding higher wages, and that lower rates will increase inflation expectations.

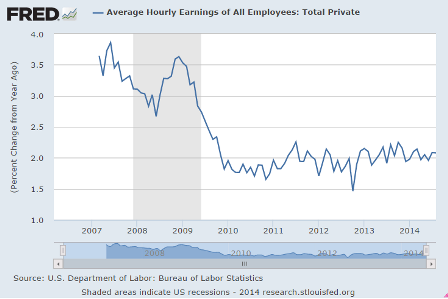

I don’t agree. First, with the currency itself a simple public monopoly, as a point of logic the price level is necessarily a function of prices paid by government when it spends (and/or collateral demanded when it lends), and not inflation expectations. And the income lost to the economy from reduced government interest payments works to reduce spending, regardless of expectations. Nor is there evidence of the collective effort required for higher expected prices to translate into higher wages. At best, organized demands for higher wages develop only well after the wage share of GDP falls.

Lower rates are further presumed to be supportive through the foreign exchange channel, causing currency depreciation that enhances ‘competitiveness’ via lower real wage costs for exporters along with an increase in inflation expectations from consumers facing higher prices for imports.

In addition to rejecting the inflation expectations channel, I also reject the presumption that lower rates cause currency depreciation and inflation, as does most empirical research. For example, after two decades of 0 rate policies the yen remained problematically strong and inflation problematically low. And the same holds for the euro and $US after many years of near zero-rate policies. In fact, theory and evidence points to the reverse- higher rates tend to weaken a currency and support higher levels of inflation.

There is another aspect to the foreign exchange channel, interest rates, and inflation. The spot and forward price for a non perishable commodity imply all storage costs, including interest expense. Therefore, with a permanent zero-rate policy, and assuming no other storage costs, the spot price of a commodity and its price for delivery any time in the future is the same. However, if rates were, say, 10%, the price of those commodities for delivery in the future would be 10% (annualized) higher. That is, a 10% rate implies a 10% continuous increase in prices, which is the textbook definition of inflation! It is the term structure of risk free rates itself that mirrors a term structure of prices which feeds into both the costs of production as well as the ability to pre-sell at higher prices, thereby establishing, by definition, inflation.

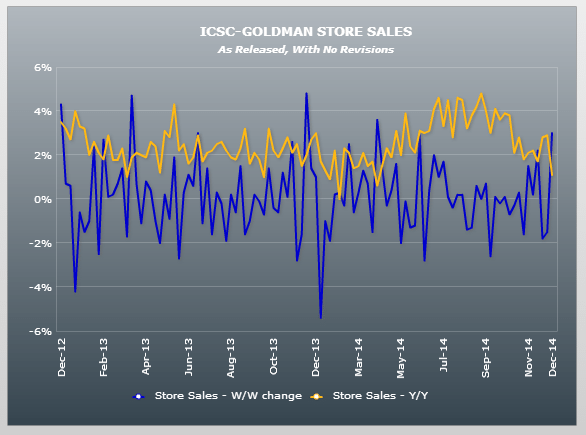

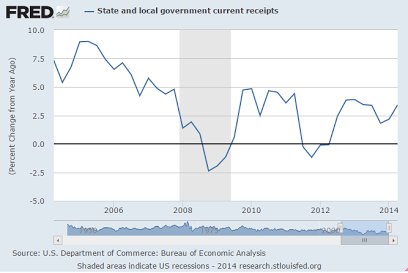

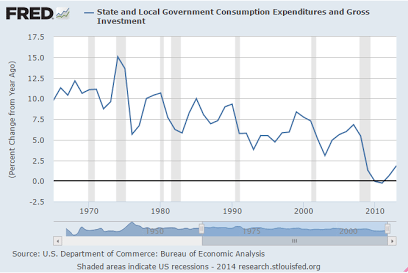

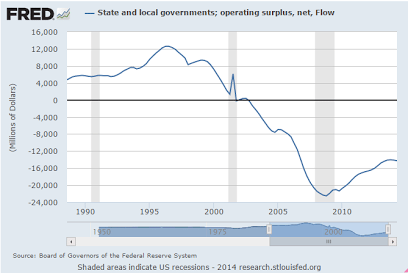

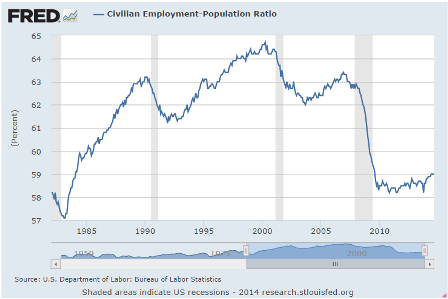

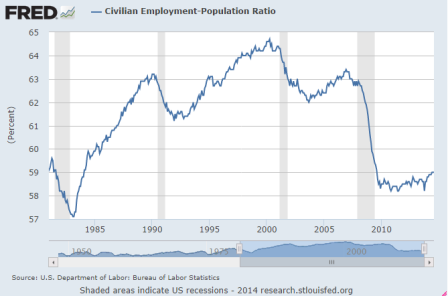

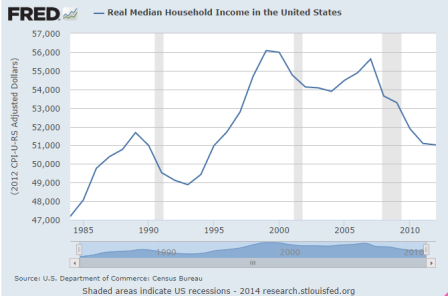

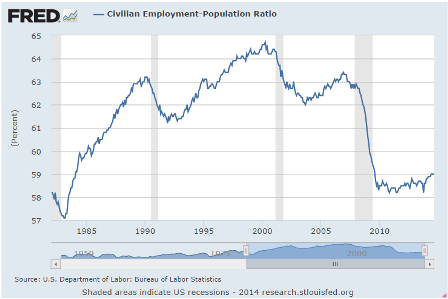

Finally, I see the output gap as being a lot higher than the mainstream does. While the total number of people reported to be working has increased, so has the population. To adjust for that look at the percentage of the population that’s employed, and it’s pretty much gone sideways since 2009, while in every prior recovery it went up at a pretty good clip once things got going:

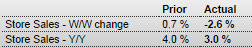

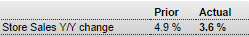

The mainstream says this drop is all largely structural, meaning people got older or otherwise decided they didn’t want to work and dropped out of the labor force. The data clearly shows that in a good economy this doesn’t happen, and certainly not to this extreme degree. Instead what we are facing is a massive shortage of aggregate demand.

Conclusion

There is no right time for the Fed to raise rates. The economy continues to fail us, and monetary policy is not capable of fixing it. Instead the fed funds rate should be permanently set at zero (further implying the Treasury sell only 3 month t bills), leaving it to Congress to employ fiscal adjustments to meet their employment and price stability mandates.