Crude pricing

The Saudis are the ‘supplier of last resort’/swing producer. Every day the world buys all the crude the other producers sell to the highest bidder and then go to the Saudis for the last 9-10 million barrels that are getting consumed. They either pay the Saudis price or shut the lights off, rendering the Saudis price setter/swing producer.

Specifically, the Saudis don’t sell at spot price in the market place, but instead simply post prices for their customers/refiners and let them buy all they want at those prices.

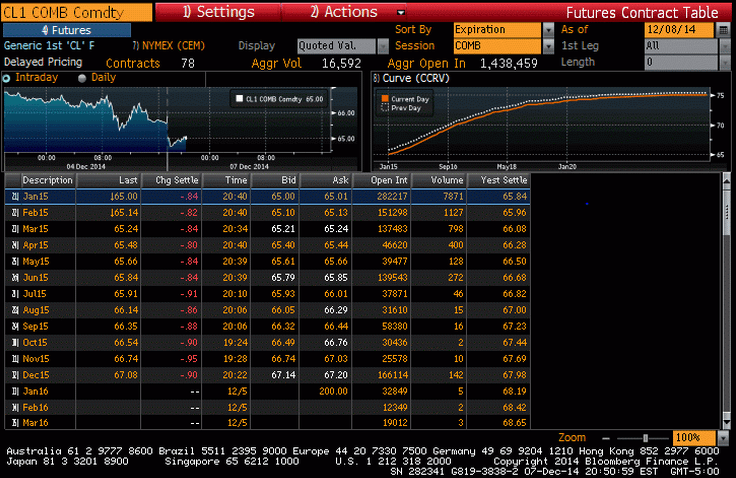

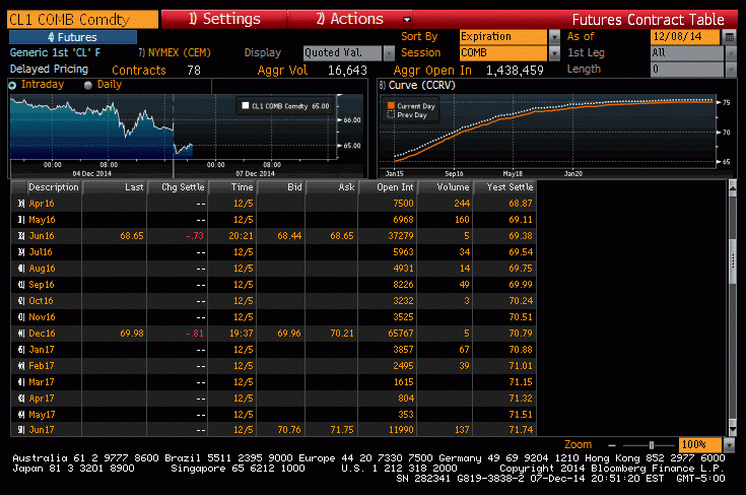

And most recently the prices they have posted have been fixed spreads from various benchmarks, like Brent.

Saudi spread pricing works like this:

Assume, for purposes of illustration, Saudi crude would sell at a discount of $1 vs Brent (due to higher refining costs etc.) if they let ‘the market’ decide the spread by selling a specific quantity at ‘market prices’/to the highest bidder. Instead, however, they announce they will sell at a $2 discount to Brent and let the refiners buy all they want.

So what happens?

The answer first- this sets a downward price spiral in motion. Refiners see the lower price available from the Saudis and lower the price they are willing to pay everyone else. And everyone else is a ‘price taker’ selling to the highest bidder, which is now $1 lower than ‘indifference levels’. When the other suppliers sell $1 lower than before the Saudi price cut/larger discount of $1, the Brent price drops by $1. Saudi crude is then available for $1 less than before, as the $2 discount remains in place. Etc. etc. with no end until either:

1) The Saudis change the discount/raise their price

2) Physical demand goes up beyond the Saudis capacity to increase production

And setting the spread north of ‘neutral’ causes prices to rise, etc.

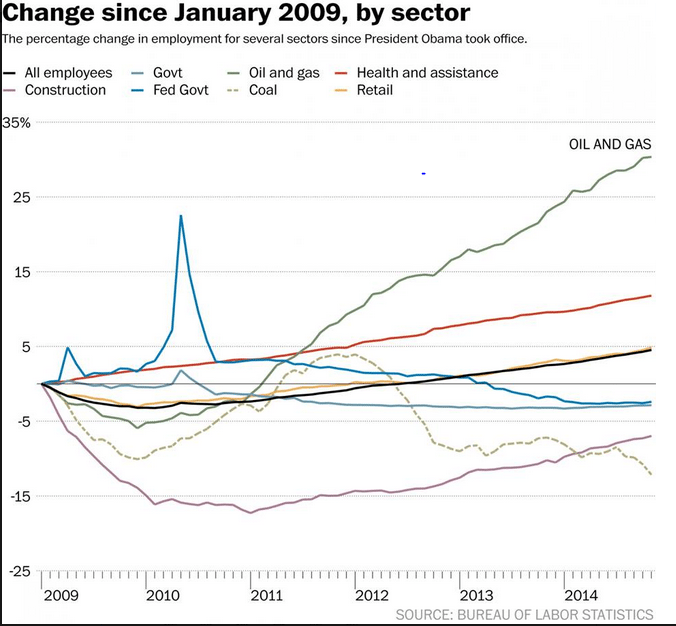

Bottom line is the Saudis set price, and have engineered the latest decline. There was no shift in net global supply/demand as evidenced by Saudi output remaining relatively stable throughout.

The Global Economy

If all the crude had simply been sold to the highest bidder/market prices, in a non monetary relative value world the amount consumed would have been ‘supply limited’ based on the real marginal cost, etc. And if prices were falling do to an increased supply offered for sale, the relative price of crude would be falling as the supply purchased and consumed rose. This would represent an increase in real output and real consumption/real GDP(yes, real emissions, etc.)

However, that’s not the case with the Saudis as price setter. The world was not operating on a ‘quantity constrained’ basis as the Saudis were continuously willing to sell more than the world wanted to purchase from them at their price. If there was any increase in non Saudi supply, total crude sales/consumption remained as before, but with the Saudis selling that much less.

Therefore, with the drop in prices, at least in the near term, output/consumption/GDP doesn’t per se go up.

Nor, in theory, in a market economy/flexible prices, does the relative value of crude change. Instead, all other prices simply adjust downward in line with the drop in crude prices.

Let me elaborate.

In a market economy (not to say that we actually have one) only one price need be set and with all others gravitating towards ‘indifference levels’. In fact, one price must be set or it’s all a ‘non starter’. So which price is set today? Mainstream economists ponder over this, and, as they’ve overlooked the fact that the currency is a public monopoly, have concluded that the price level exists today for whatever ‘historic’ reasons, and the important question is not how it got here, but what might make it change from today’s level. That is, what might cause ‘inflation’. That’s where inflation expectations theory comes in. For lack of a better reason, the ‘residual’ is that it’s inflation expectations that cause changes in the price level. And not anything else, which are relative value stories. And they operate through two channels- workers demanding higher wages and people accelerating purchases. Hence the fixation on wages as the cause of inflation, and using ‘monetary policy’ to accelerate purchases, etc.

Regardless of the ‘internal merits’ of this conclusion, it’s all obviated by the fact that the currency itself is a simple public monopoly, rendering govt price setter. Note the introduction of monetary taxation, the basis of the currency, is coercive, and obviously not a ‘market expense’ for the taxpayer, and therefore the idea of ‘neutrality’ of the currency in entirely inapplicable. In fact, since the $ to pay taxes and buy govt secs, assuming no counterfeiting, ultimately come only from the govt of issue, (as they say in the Fed, you can’t have a reserve drain without a prior reserve add), the price level is entirely a function of prices paid by the govt when it spends and/or collateral demanded when it lends. Said another way, since we need the govt’s $ to pay taxes, the govt is, whether it knows it or not, setting ‘terms of exchange’ when it buys our goods and service.

Note too that monopolists set two prices, the value of their product/price level as just described above, and what’s called the ‘own rate’/how it exchanges for itself, which for the currency is the interest rate, which is set by a vote at the CB.

The govt/mainstream, of course, has no concept of all this, as inflation expectations theory remains ‘well anchored.’ ;)

In fact, when confronted, argues aggressively that I’m wrong (story of my life- remember, they laughed at the Yugo…)

What they have done is set up a reasonably deflationary purchasing program, of buying from the lowest bidder in competition, and managed to keep federal wages/compensation a bit ‘behind the curve’ as well, partially indexed to their consumer price index, etc.

And consequently, govt has defacto advocated pricing power to the active monopolist, the Saudis, which explains why changes in crude prices and ‘inflation’ track as closely as they do.

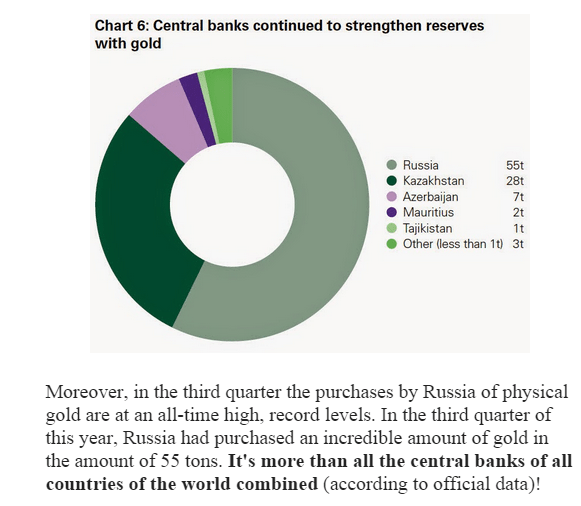

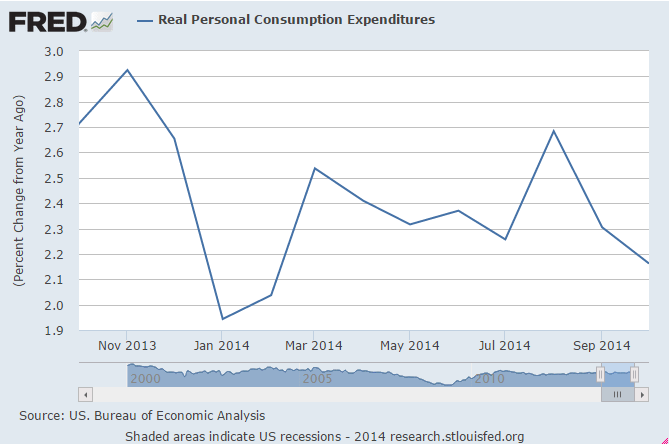

Therefore, the way I see it is the latest Saudi price cuts are revaluing the dollar (along with other currencies with similar policies, which is most all of them) higher. A dollar now buys more oil and, to the extend we have a market economy that reflects relative value, more of most everything else. That is, it’s a powerful ‘deflationary bias’ (consequently rewarding ‘savers’ at the expense of ‘borrowers’) without necessarily increasing real output.

In fact, real output could go lower due to an induced credit contraction, next up.

Banking

Deflation is highly problematic for banks. Here’s what happened at my bank to illustrate the principle:

We had a $6.5 million loan on the books with $11 million of collateral backing it. Then, in 2009 the properties were appraised at only $8 million. This caused the regulators to ‘classify’ the loan and give it only $4 million in value for purposes of calculating our assets and capital. So our stated capital was reduced by $2.5 million, even though the borrower was still paying and there was more than enough market value left to cover us.

So the point is, even with conservative loan to value ratios of the collateral, a drop in collateral values nonetheless reduces a banks reported capital. In theory, that means if the banking system needs an 8% capital ratio, and is comfortably ahead at 10%, with conservative loan to value ratios, a 10% across the board drop in assets prices introduces the next ‘financial crisis’. It’s only a crisis because the regulators make it one, of course, but that’s today’s reality.

Additionally, making new loans in a deflationary environment is highly problematic in general for similar reasons. And the reduction in ‘borrowing to spend’ on energy and related capital goods and services is also a strong contractionary bias.

Dec 4 — Saudi Arabia cuts all oil prices to U.S. and Asia, according to Bloomberg headlines.

UPDATE: Reports have the message issued by Saudi Aramco — the state-owned oil and gas giant — now recalled.