Strip private banks of their power to create money

By: Martin Wolf

The giant hole at the heart of our market economies needs to be plugged

Printing counterfeit banknotes is illegal, but creating private money is not. The interdependence between the state and the businesses that can do this is the source of much of the instability of our economies. It could – and should – be terminated.

It is perfectly legal to create private liabilities. He has not yet defined ‘money’ for purposes of this analysis

I explained how this works two weeks ago. Banks create deposits as a byproduct of their lending.

Yes, the loan is the bank’s asset and the deposit the bank’s liability.

In the UK, such deposits make up about 97 per cent of the money supply.

Yes, with ‘money supply’ specifically defined largely as said bank deposits.

Some people object that deposits are not money but only transferable private debts.

Why does it matter how they are labeled? They remain bank deposits in any case.

Yet the public views the banks’ imitation money as electronic cash: a safe source of purchasing power.

OK, so?

Banking is therefore not a normal market activity, because it provides two linked public goods: money and the payments network.

This is highly confused. ‘Public goods’ in any case aren’t ‘normal market activity’. Nor is a ‘payments network’ per se ‘normal market activity’ unless it’s a matter of competing payments networks, etc. And all assets can and do ‘provide’ liabilities.

On one side of banks’ balance sheets lie risky assets; on the other lie liabilities the public thinks safe.

Largely because of federal deposit insurance in the case of the us, for example. Uninsured liabilities of all types carry ‘risk premiums’.

This is why central banks act as lenders of last resort and governments provide deposit insurance and equity injections.

All that matters for public safety of deposits is the deposit insurance. ‘Equity injections’ are for regulatory compliance, and ‘lender of last resort’ is an accounting matter.

It is also why banking is heavily regulated.

With deposit insurance the liability side of banking is not a source of ‘market discipline’ which compels regulation and supervision as a simple point of logic.

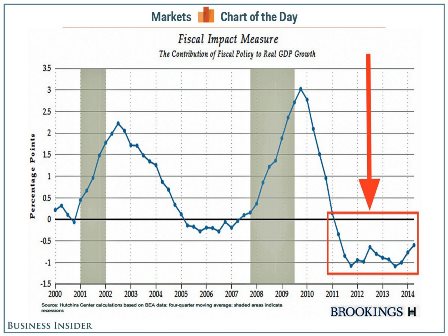

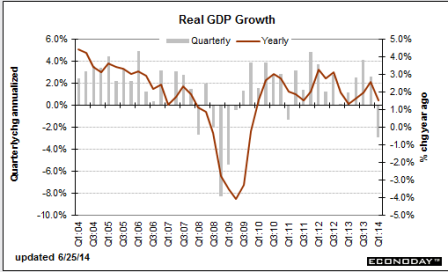

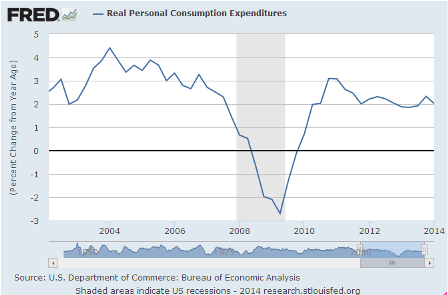

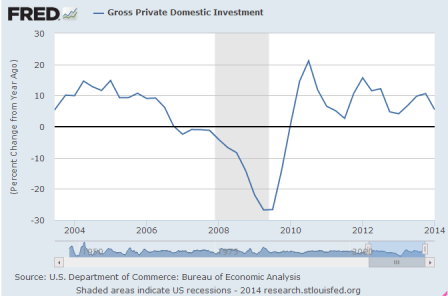

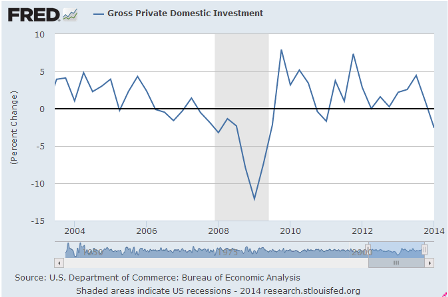

Yet credit cycles are still hugely destabilising.

Hugely destabilizing to the real economy only when the govt fails to adjust fiscal policy to sustain aggregate demand.

What is to be done?

How about aggressive fiscal adjustments to sustain aggregate demand as needed?

A minimum response would leave this industry largely as it is but both tighten regulation and insist that a bigger proportion of the balance sheet be financed with equity or credibly loss-absorbing debt. I discussed this approach last week. Higher capital is the recommendation made by Anat Admati of Stanford and Martin Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute in The Bankers’ New Clothes.

Yes, a 100% capital requirement, for example, would effectively limit lending. But, given the rest of today’s institutional structure, that would also dramatically reduce aggregate demand -spending/sales/output/employment, etc.- which is already far too low to sustain anywhere near full employment levels of output.

A maximum response would be to give the state a monopoly on money creation.

Again, ‘money’ as defined by implication above, I’ll presume. The state is already the single supplier/monopolist of that which it demands for payment of taxes.

One of the most important such proposals was in the Chicago Plan, advanced in the 1930s by, among others, a great economist, Irving Fisher.

Yes, a fixed fx/gold standard proposal.

Its core was the requirement for 100 per cent reserves against deposits.

Reserves back then were ‘real’ gold certificates.

The floating fx equiv would be 100% capital requirement.

Fisher argued that this would greatly reduce business cycles,

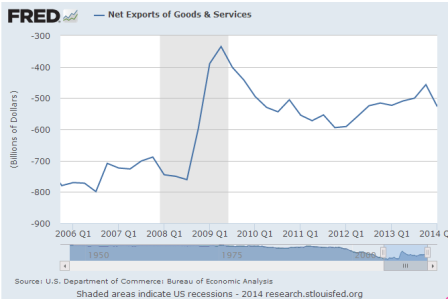

And greatly reduce aggregate demand with the idea of driving net exports to increase gold/fx reserves, or, alternatively, run larger fiscal deficit which, on the gold standard, put the nation’s gold supply at risk

end bank runs

Yes, banks would only be lending their equity, so there is nothing to ‘run’

and drastically reduce public debt.

If you wanted a vicious deflationary spiral to lower ‘real wages’ and drive net exports

A 2012 study by International Monetary Fund staff suggests this plan could work well.

No comment…

Similar ideas have come from Laurence Kotlikoff of Boston University in Jimmy Stewart is Dead, and Andrew Jackson and Ben Dyson in Modernising Money.

None of which have any kind of grasp on actual monetary operations.

Here is the outline of the latter system.

First, the state, not banks, would create all transactions money, just as it creates cash today.

Today, state spending is a matter of the CB crediting a member bank reserve account, generally for further credit to the person getting the corresponding bank deposit. The member bank has an asset, the funds credited by the CB in its reserve account, and a liability, the deposit of the person who ultimately got the funds.

If the bank depositor wants cash, his bank gets the cash from the CB, and the CB debits the bank’s reserve account. So the person who got paid holds the cash and his bank has no deposit at the CB and the person has no bank deposit.

So in this case the entire ‘money supply’ would consist of dollars spent by the govt. But not yet taxed. That’s called the deficit/national debt. That is, the govt’s deficit would = the (net) ‘money supply’ of the economy, which is exactly the way it is today.

Customers would own the money in transaction accounts,

They already do

and would pay the banks a fee for managing them.

:(

Second, banks could offer investment accounts, which would provide loans. But they could only loan money actually invested by customers.

So anyone who got paid by govt (directly or indirectly) could invest in an account so those same funds could be lent to someone else. Again, by design, this is to limit lending. And with ‘loanable funds’ limited in this way, the interest rate would reflect supply and demand for borrowing those funds, much like and fixed exchange rate regime.

So imagine a car company with a dip in sales and a bit of extra unsold inventory, that has to borrow to finance that inventory. It has to compete with the rest of the economy to borrow a limited amount of available funds (limited by the ‘national debt’). In a general slowdown it means rates will skyrocket to the point where companies are indifferent between paying the going interest rate and/or immediately liquidating inventory. This is called a fixed fx deflationary collapse.

They would be stopped from creating such accounts out of thin air and so would become the intermediaries that many wrongly believe they now are. Holdings in such accounts could not be reassigned as a means of payment. Holders of investment accounts would be vulnerable to losses. Regulators might impose equity requirements and other prudential rules against such accounts.

As above.

Third, the central bank would create new money as needed to promote non-inflationary growth. Decisions on money creation would, as now, be taken by a committee independent of government.

What does ‘create new money’ mean in this context? If they spend it, that’s fiscal. If they lend it, how would that work? In a deflationary collapse there are no ‘credit worthy borrowers’ as they system is in technical default due to ‘unspent income’ issues. Would they somehow simply lend to support a target rate of interest? Which brings us back to what we have today, apart from deciding who to lend to at that rate, the way today’s banks decide who to lend to? And it becomes a matter of ‘public bank’ vs ‘private bank’, but otherwise the same?

Finally, the new money would be injected into the economy in four possible ways: to finance government spending,

That’s deficit spending, as above, and no distinction regards to current policy

in place of taxes or borrowing;

Same as above. For all practical purposes, all govt spending is via crediting a member bank account.

to make direct payments to citizens;

Same thing- net fiscal expenditure

to redeem outstanding debts, public or private;

Same

or to make new loans through banks or other intermediaries.

As above, that’s just a shift from private banking to public banking, and nothing more.

All such mechanisms could (and should) be made as transparent as one might wish.

The transition to a system in which money creation is separated from financial intermediation would be feasible, albeit complex.

No, it’s quite simple actually, as above.

But it would bring huge advantages. It would be possible to increase the money supply without encouraging people to borrow to the hilt.

Deficit spending does that.

It would end “too big to fail” in banking.

That’s just a matter of shareholders losing when things go bad which is already the case.

It would also transfer seignorage – the benefits from creating money – to the public.

That’s just a bunch of inapplicable empty rhetoric with today’s floating fx regimes.

In 2013, for example, sterling M1 (transactions money) was 80 per cent of gross domestic product. If the central bank decided this could grow at 5 per cent a year, the government could run a fiscal deficit of 4 per cent of GDP without borrowing or taxing.

In any case spending in excess of taxing adds to bank reserve accounts, and if govt doesn’t pay interest on those accounts or offer interest bearing alternatives, generally called securities accounts, the consequence is a 0% rate policy. So seems this is a proposal for a permanent zero rate policy, which I support!!! But that doesn’t require any of the above institutional change, just an announcement by the cb that zero rates are permanent.

The right might decide to cut taxes, the left to raise spending. The choice would be political, as it should be.

And exactly as it is today in any case

Opponents will argue that the economy would die for lack of credit.

Not if the deficit spending is allowed to ‘shift’ from private to public.

I was once sympathetic to that argument. But only about 10 per cent of UK bank lending has financed business investment in sectors other than commercial property. We could find other ways of funding this.

Govt deficit spending or net exports are the only two alternatives.

Our financial system is so unstable because the state first allowed it to create almost all the money in the economy

The process is already strictly limited by regulation and supervision

and was then forced to insure it when performing that function.

The liability side of banking isn’t the place for market discipline, hence deposit insurance.

This is a giant hole at the heart of our market economies. It could be closed by separating the provision of money, rightly a function of the state, from the provision of finance, a function of the private sector.

The funds to pay taxes already come only from the state.

The problem is that leadership doesn’t understand monetary operations.

This will not happen now. But remember the possibility. When the next crisis comes – and it surely will – we need to be ready.

Agreed!!!!!