Plosser Speach

Some comments below:

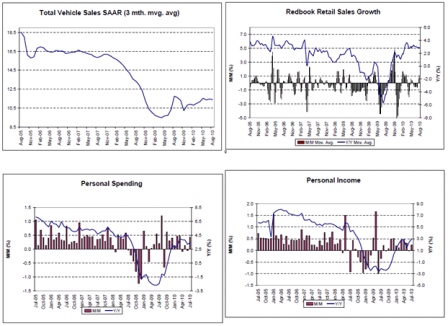

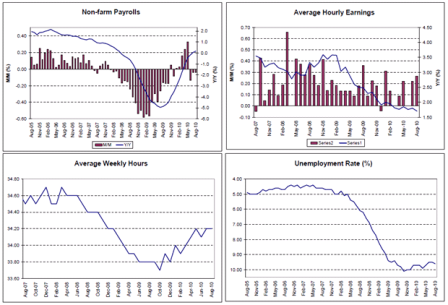

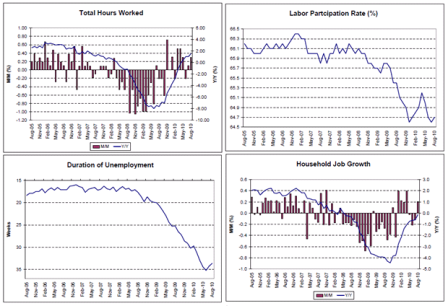

Let me begin by noting that the economy has gained significant strength and momentum since late last summer and seems to be on a much firmer foundation going forward. Consumer spending continues to expand at a reasonably robust pace, and business investment, particularly on equipment and software, continues to support overall growth. Labor market conditions are improving. Firms are adding to their payrolls, which will result in continued modest declines in the unemployment rate. The residential and commercial real estate sectors remain weak but appear to have stabilized. Nevertheless, I do not believe that weakness in these sectors will prevent a broader economic recovery. Indeed, the nonresidential real estate sector is likely to improve as the overall economy gains ground.

If this forecast is broadly accurate, then monetary policy will have to reverse course in the not-too-distant future and begin to remove the massive amount of accommodation it has supplied to the economy.

No it won’t. As the Fed’s own Kohn and Carpenter have stated, there is no ‘monetary channel’ from reserves to anything else.

Failure to do so in a timely manner could have serious consequences for inflation and economic stability in the future.

Not true.

But what matters is that pretty much the entire FOMC believes it to be true and will act accordingly.

Market participants also believe it to be true and shift portfolios accordingly.

To avoid this outcome, the Fed must confront at least two challenges. The first is selecting the appropriate time to begin unwinding the accommodation. The second is how to use the available tools to move monetary policy toward a more neutral stance over time.

Looks to me like the current situation- 2 years of very modest gdp growth, high unemployment that is forecast to fall only slowly, and very little signs of private credit expanding- is telling us policy is already relatively neutral, given the circumstances.

First, monetary policy should operate using the federal funds rate as its policy instrument. Because the Fed can now pay interest on reserves, monetary policy could use the interest rate on reserves (IOR) as its instrument, establishing a floor for rates and allow reserves to be supplied in an elastic manner.3 However, targeting the federal funds rate is more familiar to both the markets and policymakers than is an administered rate paid on reserves. To make the funds rate the primary policy instrument, the target federal funds rate would be set above the rate paid on reserves and below the discount or primary credit rate that banks pay when they borrow from the Fed.

This means the that at the margin the NY Fed has to keep the banks net borrowed to keep the fed funds rate above the floor, and net long to keep it below the ceiling.

Good luck and who cares if the rate paid on reserves equals the fund funds rate?

This operating framework is sometimes referred to as a corridor or channel system and is used by a number of other central banks around the world.4 I have argued elsewhere that our goal should be to operate with a corridor system instead of a floor system,

Yes, this greatly simplifies life for the NY Fed trading desk, especially if you allow fed funds to trade at the floor rate. The should have done it a long time ago, like most other CB’s in the world. And while they are at it, they should also drop reserve requirements, like Canada did a while back, and get rid of that anachronism. (I recall being at a monetary conference in Canada, where a senior monetary crank- sorry, I mean senior mainstream economist- was on a rant about how dropping reserve requirements to 0 was going to be hyper inflationary.)

in part because it constrains the size of the balance sheet while the floor system does not.

Like the salesman who went on after he made the sale and discredited himself. This last part again reveals is anachronistic, gold standard understanding of monetary operations.

The second element of the environment follows from the first. To ensure that the funds rate constitutes a viable policy instrument and thus is above the interest rate on reserves, the volume of reserves in the banking system must shrink to the point where the demand for reserves is consistent with the targeted funds rate. This will require a significant reduction in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, with reserve balances falling by $1.4 trillion to $1.5 trillion to about $50 billion.

Yes, pretty much the problem I described above.

So why would the fed funds rate not be ‘a viable policy instrument’ if it equaled the rate of interest the Fed payed on reserves?

My proposed strategy involves raising rates and shrinking the balance sheet concurrently and tying the pace of asset sales to the pace and size of interest rate increases.8

The important thing here is not the wisdom of the policy, but that these statements are in fact what the FOMC is likely to be doing.

The first element of the plan to exit and normalize policy would be to move away from the zero bound and stop the reinvesting program and allow securities to run off as they mature. Thus, we would raise the interest paid on reserves from 25 basis points to 50 basis points and seek to achieve a funds rate of 50 basis points rather than the current range of 0 to 25 basis points.

This indicates the fed funds rate and the interest paid on reserves would be roughly equal, which makes sense operationally.

We would also announce that between each FOMC meeting, in addition to allowing assets to run off as they mature or are prepaid, we would sell an additional specified amount of assets. These “continuous sales,” plus the natural run-off, imply that the balance sheet, and thus reserves, would gradually shrink between each FOMC meeting on an ongoing basis.

Again, good to know what they plan on doing. And it seems this time around the all seem pretty much to be on the same page. At least so far.

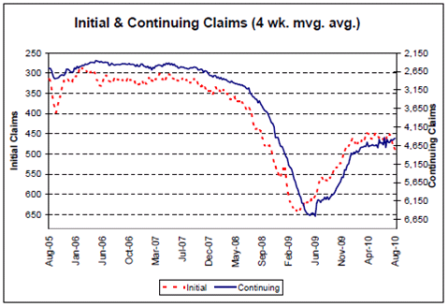

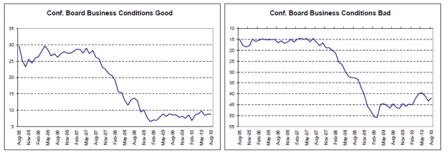

Now the remaining question is whether the employment outlook will improve sufficiently and core inflation measures stabilize sufficiently in the FOMC’s comfort zone for them to begin ‘removing accommodation’ as they call it.

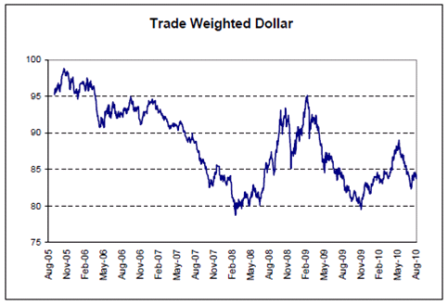

I’d suggest that could be by Q4 if not for the global bias towards ‘fiscal responsibility’ along with the inflation fighting going on in China which threatens to keep output gaps wide and employment low.

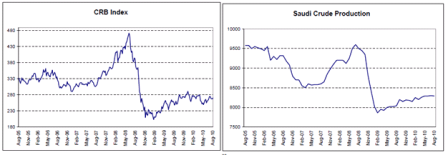

And at least so far price pressures are mainly from crude oil, which the Fed (rightly) considers a ‘relative value story’ and from food prices, which are closely related to fuel prices through various bio fuels and fertilizer inputs. Wages and unit labor costs remain subdued and with productivity relatively high there are, so far, no signs of ‘pass through’ from food and fuel prices to core measures.

The second element of the plan would be to announce that at each subsequent meeting the FOMC will, as usual, evaluate incoming data to determine if the interest rate on reserves and the funds rate should rise or not. Monetary policy should be conditional on the state of the economy and the outlook. If the funds rate and interest on excess reserves do not change, the balance sheet would continue to shrink slowly due to run-off and the continuous sales. On the other hand, if the FOMC decides to raise rates by 25 basis points, it would automatically trigger additional asset sales of a specified amount during the intermeeting period. This approach makes the pace of asset sales conditional on the state of the economy, just as the Fed’s interest rate decisions are. If it were necessary to raise the interest rate target more, say, by 50 basis points, because the economy was improving faster and inflation expectations were rising, then the pace of conditional sales would also be doubled during the intermeeting period.10