Here’s my take on the Volcker article

My comments in below:

By Paul Volcker

I have been struck by parallels between the challenges facing the Federal Reserve today and those when I first entered the Federal Reserve System as a neophyte economist in 1949.

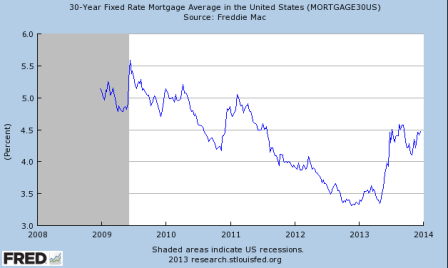

Most striking then, as now, was the commitment of the Federal Reserve, which was and is a formally independent body, to maintaining a pattern of very low interest rates, ranging from near zero to 2.5 percent or less for Treasury bonds. If you feel a bit impatient about the prevailing rates, quite understandably so, recall that the earlier episode lasted fifteen years.

The initial steps taken in the midst of the depression of the 1930s to support the economy by keeping interest rates low were made at the Fed’s initiative. The pattern was held through World War II in explicit agreement with the Treasury. Then it persisted right in the face of double-digit inflation after the war, increasingly under Treasury and presidential pressure to keep rates low.

Yes, and this was done after conversion to gold was suspended which made it possible. And they fixed long rates as well/

The growing restiveness of the Federal Reserve was reflected in testimony by Marriner Eccles in 1948:

Under the circumstances that now exist the Federal Reserve System is the greatest potential agent of inflation that man could possibly contrive.

This was pretty strong language by a sitting Fed governor and a long-serving board chairman. But it was then a fact that there were many doubts about whether the formality of the independent legal status of the central bank—guaranteed since it was created in 1913—could or should be sustained against Treasury and presidential importuning. At the time, the influential Hoover Commission on government reorganization itself expressed strong doubts about the Fed’s independence. In these years calls for freeing the market and letting the Fed’s interest rates rise met strong resistance from the government.

Not freeing the ‘market’ but letting the Fed chair have his way. Rates would be set ‘politically’ either way. Just a matter of who.

Treasury debt had enormously increased during World War II, exceeding 100 percent of the GDP, so there was concern about an intolerable impact on the budget if interest rates rose strongly. Moreover, if the Fed permitted higher interest rates this might lead to panicky and speculative reactions. Declines in bond prices, which would fall as interest rates rose, would drain bank capital. Main-line economists, and the Fed itself, worried that a sudden rise in interest rates could put the economy back in recession.

All of those concerns are in play today, some sixty years later, even if few now take the extreme view of the first report of the then new Council of Economic Advisers in 1948: “low interest rates at all times and under all conditions, even during inflation,” it said, would be desirable to promote investment and economic progress. Not exactly a robust defense of the Federal Reserve and independent monetary policy.

But in my humble opinion a true statement!

Eventually, the Federal Reserve did get restless, and finally in 1951 it rejected overt presidential pressure to maintain a ceiling on long-term Treasury rates. In the event, the ending of that ceiling, called the “peg,” was not dramatic. Interest rates did rise over time, but with markets habituated for years to a low interest rate, the price of long-term bonds remained at moderate levels. Monetary policy, free to act against incipient inflationary tendencies, contributed to fifteen years of stability in prices, accompanied by strong economic growth and high employment. The recessions were short and mild.

I agreed with John Kenneth Galbraith in that inflation was not a function of rates, at least not in the direction they believed, due to interest income channels. However, the rate caps on bank deposits, etc. Did mean that rate hikes had the potential to disrupt those financial institutions and cut into lending, until those caps were removed.

In general, however, the ‘business cycle’ issues are better traced to fiscal balance.

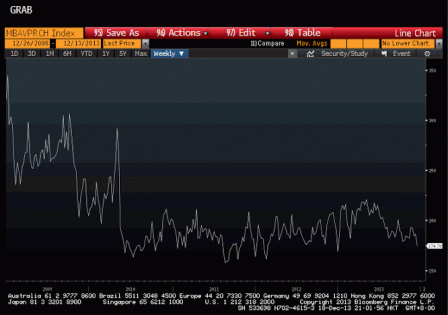

No doubt, the challenge today of orderly withdrawal from the Fed’s broader regime of “quantitative easing”—a regime aimed at stimulating the economy by large-scale buying of government and other securities on the market—is far more complicated. The still-growing size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet imply the need for, at the least, an extended period of “disengagement,” i.e., less active purchasing of bonds so as to keep interest rates artificially low.

Artificially? vs what ‘market signals’? Rates are ‘naturally’ market determined with fixed fx policies, not today’s floating fx.

In fact, without govt ‘interference’ such as interest on reserves and tsy secs, the ‘natural’ rate is 0 as long as there are net reserve balances from deficit spending.

Nor is there any technical or operational reason for unwinding QE. Functionally, the Fed buying securities is identical to the tsy not issuing them and instead letting its net spending remain as reserve balances. Either way deficit spending results in balances in reserve accounts rather than balances in securities accounts. And in any case both are just dollar balances in Fed accounts.

Moreover, the extraordinary commitment of Federal Reserve resources,

‘Resources’? What does that mean? Crediting an account on its own books is somehow ‘using up a resource’? It’s just accounting information!

alongside other instruments of government intervention, is now dominating the largest sector of our capital markets, that for residential mortgages. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to note that the Federal Reserve, with assets of $3.5 trillion and growing, is, in effect, acting as the world’s largest financial intermediator. It is acquiring long-term obligations in the form of bonds and financing those purchases by short-term deposits. It is aided and abetted in doing so by its unique privilege to create its own liabilities.

The Fed creates govt liabilities, aka making payments. That’s its function. And, for example, the treasury securities are the initial intervention. They are paid for by the Fed debiting reserve accounts and crediting securities accounts. All QE does is reverse that as the Fed debits the securities accounts and ‘recredits’ the reserve accounts. So it can be said that all QE does is neutralize prior govt intervention.

The beneficial effects of the actual and potential monetizing of public and private debt, which is the essence of the quantitative easing program, appear limited and diminishing over time. The old “pushing on a string” analogy is relevant. The risks of encouraging speculative distortions and the inflationary potential of the current approach plainly deserve attention.

Right, with the primary fundamental effect being the removal of interest income from the economy. The Fed turned over some $100billion to the tsy that the economy would have otherwise earned. QE is a tax on the economy.

All of this has given rise to debate within the Federal Reserve itself. In that debate, I trust that sight is not lost of the merits—economic and political—of an ultimate return to a more orthodox central banking approach. Concerning possible changes in Fed policy, it is worth quoting from Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s remarks on June 19:

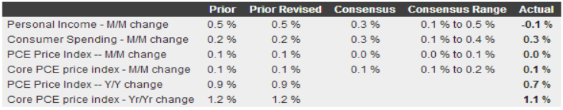

Going forward, the economic outcomes that the Committee sees as most likely involve continuing gains in labor markets, supported by moderate growth that picks up over the next several quarters as the near-term restraint from fiscal policy and other headwinds diminishes. We also see inflation moving back toward our 2 percent objective over time.

If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of [asset] purchases later this year. And if the subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear.

In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7 percent, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains, a substantial improvement from the 8.1 percent unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this program.

I would like to emphasize once more the point that our policy is in no way predetermined and will depend on the incoming data and the evolution of the outlook as well as on the cumulative progress toward our objectives. If conditions improve faster than expected, the pace of asset purchases could be reduced somewhat more quickly. If the outlook becomes less favorable, on the other hand, or if financial conditions are judged to be inconsistent with further progress in the labor markets, reductions in the pace of purchases could be delayed.

Indeed, should it be needed, the Committee would be prepared to employ all of its tools, including an increase in the pace of purchases for a time, to promote a return to maximum employment in a context of price stability.

Implying QE works to do that.

I do not doubt the ability and understanding of Chairman Bernanke and his colleagues. They have a considerable range of instruments available to them to manage the transition, including the novel approach of paying interest on banks’ excess reserves, potentially sterilizing their monetary impact.

Reserves can be thought of as ‘one day treasury securities’ and the idea that paying interest sterilizing anything is a throwback to fixed fx policy, not applicable to floating fx.

What is at issue—what is always at issue—is a matter of good judgment, leadership, and institutional backbone. A willingness to act with conviction in the face of predictable political opposition and substantive debate is, as always, a requisite part of a central bank’s DNA.

A good working knowledge of monetary operations would be a refreshing change as well!

Those are not qualities that can be learned from textbooks. Abstract economic modeling and the endless regression analyses of econometricians will be of little help. The new approach of “behavioral” economics itself is recognition of the limitations of mathematical approaches, but that new “science” is in its infancy.

Monetary operations can be learned from money and banking texts.

A reading of history may be more relevant. Here and elsewhere, the temptation has been strong to wait and see before acting to remove stimulus and then moving toward restraint. Too often, the result is to be too late, to fail to appreciate growing imbalances and inflationary pressures before they are well ingrained.

Those who know monetary operations read history very differently from those who have it wrong.

There is something else that is at stake beyond the necessary mechanics and timely action. The credibility of the Federal Reserve, its commitment to maintaining price stability, and its ability to stand up against partisan political pressures are critical. Independence can’t just be a slogan. Nor does the language of the Federal Reserve Act itself assure protection, as was demonstrated in the period after World War II. Then, the law and its protections seemed clear, but it was the Treasury that for a long time called the tune.

And didn’t do a worse job.

In the last analysis, independence rests on perceptions of high competence, of unquestioned integrity, of broad experience, of nonconflicted judgment and the will to act. Clear lines of accountability to Congress and the public will need to be honored.

And a good working knowledge of monetary operations.

Moreover, maintenance of independence in a democratic society ultimately depends on something beyond those institutional qualities. The Federal Reserve—any central bank—should not be asked to do too much, to undertake responsibilities that it cannot reasonably meet with the appropriately limited powers provided.

I know that it is fashionable to talk about a “dual mandate”—the claim that the Fed’s policy should be directed toward the two objectives of price stability and full employment. Fashionable or not, I find that mandate both operationally confusing and ultimately illusory. It is operationally confusing in breeding incessant debate in the Fed and the markets about which way policy should lean month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter with minute inspection of every passing statistic. It is illusory in the sense that it implies a trade-off between economic growth and price stability, a concept that I thought had long ago been refuted not just by Nobel Prize winners but by experience.

The Federal Reserve, after all, has only one basic instrument so far as economic management is concerned—managing the supply of money and liquidity.

Completely wrong. With floating fx, it can only set rates. It’s always about price, not quantity.

Asked to do too much—for example, to accommodate misguided fiscal policies, to deal with structural imbalances, or to square continuously the hypothetical circles of stability, growth, and full employment—it will inevitably fall short. If in the process of trying it loses sight of its basic responsibility for price stability, a matter that is within its range of influence, then those other goals will be beyond reach.

Back in the 1950s, after the Federal Reserve finally regained its operational independence, it also decided to confine its open market operations almost entirely to the short-term money markets—the so-called “Bills Only Doctrine.” A period of remarkable economic success ensued, with fiscal and monetary policies reasonably in sync, contributing to a combination of relatively low interest rates, strong growth, and price stability.

Yes, and the price of oil was fixed by the Texas railroad commission at about $3 where it remained until the excess capacity in the US was gone and the Saudis took over that price setting role in the early 70’s.

That success faded as the Vietnam War intensified, and as monetary and fiscal restraints were imposed too late and too little. The absence of enough monetary discipline in the face of the overt inflationary pressures of the war left us with a distasteful combination of both price and economic instability right through the 1970s—a combination not inconsequentially complicated further by recurrent weakness in the dollar.

No mention of a foreign ‘monopolist’ hiking crude prices from 3 to 40?

Or of Carter’s deregulation of nat gas in 78 causing OPEC to drown in excess capacity in the early 80’s?

Or the non sensical targeting of borrowed reserves that worked only to shift rate control from the FOMC to the NY fed desk, and prolonged the inflation even as oil prices collapsed?

We cannot “go home again,” not to the simpler days of the 1950s and 1960s. Markets and institutions are much larger, far more complex. They have also proved to be more fragile, potentially subject to large destabilizing swings in behavior. There is the rise of “shadow banking”—the nonbank intermediaries such as investment banks, hedge funds, and other institutions overlapping commercial banking activities.

Not to mention restaurants letting people eat before they pay for their meals. This completely misses the mark.

Partly as a result, there is the relative decline of regulated commercial banks, and the rapid innovation of new instruments such as derivatives. All these have challenged both central banks and other regulatory authorities around the developed world. But the simple logic remains; and it is, in fact, reinforced by these developments. The basic responsibility of a central bank is to maintain reasonable price stability—and by extension to concern itself with the stability of financial markets generally.

In my judgment, those functions are complementary and should be doable.

They are, but it all requires an understanding of the underlying monetary operations.

I happen to believe it is neither necessary nor desirable to try to pin down the objective of price stability by setting out a single highly specific target or target zone for a particular measure of prices. After all, some fluctuations in prices, even as reflected in broad indices, are part of a well-functioning market economy. The point is that no single index can fully capture reality, and the natural process of recurrent growth and slowdowns in the economy will usually be reflected in price movements.

With or without a numerical target, broad responsibility for price stability over time does not imply an inability to conduct ordinary countercyclical policies. Indeed, in my judgment, confidence in the ability and commitment of the Federal Reserve (or any central bank) to maintain price stability over time is precisely what makes it possible to act aggressively in supplying liquidity in recessions or when the economy is in a prolonged period of growth but well below its potential.

With floating fx bank liquidity is always infinite. That’s what deposit insurance is all about.

Again, this makes central banking about price and not quantity.

—

Feel free to distribute.