The joke used to be: ‘what’s the difference between bonds and bond traders?

Bonds eventually mature.

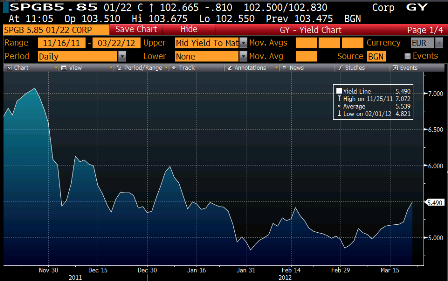

Except in the euro zone, post the Greek PSI ‘bond tax’, markets are starting to trade like maybe the don’t.

Yes, the ECB can come in and buy again, and probably will with more deterioration, but now it’s known that merely increases the risk of holding the remaining outstanding bonds, as the ECB’s bonds become ‘senior’and don’t get taxed.

So with deficits looking higher due to economic weakness due to mandatory austerity, the sustainability maths pointing to the bond tax route, and the ECB buying further adding to risk of loss, something has to give.

And it all remains potentially catastrophic for the global financial infrastructure, with aggregate demand remaining on the weak side globally and fiscal consolidation pending in most places.