Review:

Financially, the euro zone member nations have put themselves in the position of the US States.

Their spending is revenue constrained. They must tax or borrow to fund their spending.

The ECB is in the position of the Fed. They are not revenue constrained. Operationally, they spend by changing numbers on their own spread sheet.

Applicable history:

The US economy’s annual federal deficits of over 8% of gdp, Japan’s somewhere near there, and the euro zone is right up there as well.

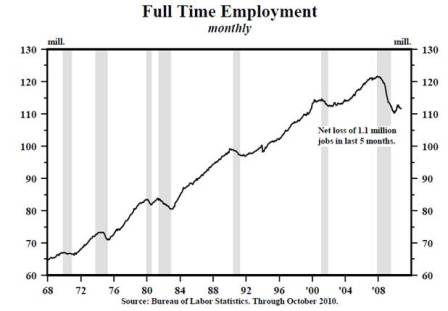

And they are still far too restrictive as evidenced by the unemployment rates and excess capacity in general.

So why does the world require high levels of deficit spending to achieve fiscal neutrality?

It’s the deadly innocent fraud, ‘We need savings to have money for investment’ as outlined in non technical language in my book.

The problem is that no one of political consequence understands that monetary savings is nothing more than the accounting record of investment.

And, therefore, it’s investment that ’causes’ savings.

Not only don’t we need savings to fund investment, there is no such thing.

But all believe we do. And they also believe we need more investment to drive the economy (another misconception of causations, but that’s another story for another post).

So the US, Japan, and the euro zone has set up extensive savings incentives, which, for all practical purposes, function as taxes, serving to remove aggregate demand (spending power). These include tax advantaged pension funds, insurance and other corporate reserves, etc.

This means someone has to spend more than their income or the output doesn’t get sold, and it’s business that goes into debt funding unsold inventory. Unsold inventory kicks in a downward spiral, with business cutting back, jobs and incomes lost, lower sales, etc. until there is sufficient spending in excess of incomes to stabilize things.

This spending more than income has inevitably comes from automatic fiscal stabilizers- falling revenues and increased transfer payments due to the slowdown- that automatically cause govt to spend more than its income.

And so here we are:

The stabilization at the current output gap has largely come from the govt deficit going up due to the automatic stabilizers, though with a bit of help from proactive govt fiscal adjustments.

Note that low interest rates, both near 0 short term rates and lower long rates helped down a bit by QE, have not done much to cause consumers and businesses to spend more than their incomes- borrow to spend- and support GDP through the credit expansion channel.

I’ve always explained why that always happened by pointing to the interest income channels. Lower rates shift income from savers to borrowers, and the economy is a net saver. So, overall, lower rates reduce interest income for the economy. The lower rates also tend to shift interest income from savers to banks, as net interest margins for lenders seem to widen as rates fall. Think of the economy as going to the bank for a loan. Interest rates are a bit lower which helps, but the economy’s income is down. Which is more important? All the bankers I’ve ever met will tell you the lower income is the more powerful influence.

Additionally, banks and other lenders are necessarily pro cyclical. During a slowdown with falling collateral values and falling incomes it’s only prudent to be more cautious. Banks do strive to make loans only to those who can pay them back, and investors do strive to make investments that will provide positive returns.

The only sector that can act counter cyclically without regard to its own ability to fund expenditures is the govt that issues the currency.

So what’s been happening over the last few decades?

The need for govt to tax less than it spends (spend more than its income) has been growing as income going to the likes of pension funds and corporate reserves has been growing beyond the ability of the private sector to expand its credit driven spending.

And most recently it’s taken extraordinary circumstances to drive private credit expansion sufficiently for full employment conditions.

For example, In the late 90’s it took the dot com boom with the funding of impossible business plans to bring unemployment briefly below 4%, until that credit expansion became unsustainable and collapsed, with a major assist from the automatic fiscal stabilizers acting to increase govt revenues and cut spending to the point of a large, financial equity draining budget surplus.

And then, after rate cuts did nothing, and the slowdown had caused the automatic fiscal stabilizers had driven the federal budget into deficit, the large Bush proactive fiscal adjustment in 2003 further increased the federal deficit and the economy began to modestly improve. Again, this got a big assist from an ill fated private sector credit expansion- the sub prime fraud- which again resulted in sufficient spending beyond incomes to bring unemployment down to more acceptable levels, though again all to briefly.

My point is that the ‘demand leakages’ from tax advantaged savings incentives have grown to the point where taxes need to be lot lower relative to govt spending than anyone seems to understand.

And so the only way we get anywhere near a good economy is with a dot com boom or a sub prime fraud boom.

Never with sound, proactive policy.

Especially now.

For the US and Japan, the door is open for taxes to be that much lower for a given size govt. Unfortunately, however, the politicians and mainstream economists believe otherwise.

They believe the federal deficits are too large, posing risks they can’t specifically articulate when pressed, though they are rarely pressed by the media who believe same.

The euro zone, however has that and much larger issues as well.

The problem is the deficits from the automatic stabilizers are at the member nation level, and therefore they do result in member nation insolvency.

In other words, the demand leakages (pension fund contributions, etc.) require offsetting deficit spending that’s beyond the capabilities of the national govts to deficit spend.

The only possible answer (as I’ve discussed in previous writings, and gotten ridiculed for on CNBC) is for the ECB to directly or indirectly ‘write the check’ as has been happening with the ECB buying of member nation debt in the secondary markets.

But this is done only ‘kicking and screaming’ and not as a matter of understanding that this is a matter of sound fiscal policy.

So while the ECB’s buying is ongoing, so are the noises to somehow ‘exit’ this policy.

I don’t think there is an exit to this policy without replacing it with some other avenue for the required ECB check writing, including my continuing alternative proposals for ECB distributions, etc.

The other, non ECB funding proposals could buy some time but ultimately don’t work. Bringing in the IMF is particularly curious, as the IMF’s euros come from the euro members themselves, as do the euro from the other funding schemes. All that the core member nations funding the periphery does is amplify the solvency issues of the core, which are just as much in ponzi (dependent on further borrowing to pay off debt) as all the rest.

So what we are seeing in the euro zone is a continued muddling through with banks and govts in trouble, deposit insurance and member govts kept credible only by the ECB continuing to support funding of both banks and the national govts, and a highly deflationary policy of ECB imposed ‘fiscal responsibility’ that’s keeping a lid on real economic growth.

The system will not collapse as long as the ECB keeps supporting it, and as they have taken control of national govt finances with their imposed ‘terms and conditions’ they are also responsible for the outcomes.

This means the ECB is unlikely to pull support because doing so would be punishing itself for the outcomes of its own imposed policies.

Is the euro going up or down?

Many cross currents, as is often the case. My conviction is low at the moment, but that could change with events.

The euro policies continue to be deflationary, as ECB purchases are not yet funding expanded member nation spending. But this will happen when the austerity measures cause deficits to rise rather than fall. But for now the ECB imposed terms and conditions are keeping a lid on national govt spending.

The US is going through its own deflationary process, as fiscal is tightening slowly with the modest GDP growth. Also the mistaken presumption that QE is somehow inflationary and weakens the currency has resulted in selling of the dollar for the wrong reasons, which seems to be reversing.

China is dealing with its internal inflation which can reverse capital flows and result in a reduction of buying both dollars and euro. It can also lead to lower demand for commodities and lower prices, which probably helps the dollar more than the euro. And a slowing China can mean reduced imports from Germany which would hurt the euro some.

Japan is the only nation looking at fiscal expansion, however modest. It’s also sold yen to buy dollars, which helps the dollar more than the euro.

The UK seems to be tightening fiscal more rapidly than even the euro zone or the US, helping sterling to over perform medium term.

All considered, looks to me like dollar strength vs most currencies, perhaps less so vs the euro than vs the yen or commodity currencies. But again, not much conviction at the moment, beyond liking short UK cds vs long Germany cds….

Happy turkey!

(Next year in Istanbul, to see where it all started…)