More from the AVM 1996 conference anticipating today’s issues attached.

Feel free to distribute:

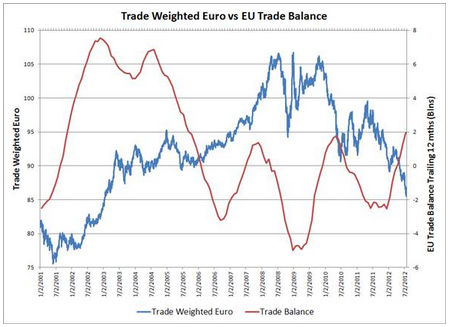

Interesting dynamics at work. Trade can drive the currency and/or the currency can drive trade.

Looks to me like early on it was the trade that was driving up the currency, But more recently the currency looks to be driving trade.

That is, portfolio managers have been shifting out of euro due to the crisis, cheapening it to the point where the trade flows are on the other side of their portfolio shifting.

For example, someone selling his euro for dollars is effectively selling them to an American tourist buying tacos in Spain. Euros shift from the portfolio manager to the Spanish exporter.

Trade flows are generally large, price driven ships to turn around, and continuous as well. Portfolio shifts, while they can also be large, are more often ‘one time’ events, driven by fear/psychology, as has likely been the case with the euro. So a turn in psychology that ‘rebalances’ portfolios to more ‘normal’ ratios can be very euro friendly.

>

> (email exchange)

>

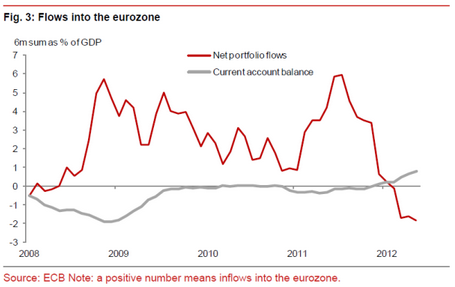

> This was an interesting chart from Nomura that came out over the weekend discussing

> the current account against the portfolio flows – suggests that the portfolio flows

> have turned significantly negative for Europe and are much bigger than the positive

> effects of the current account.

>

Yes, agreed. this says much the same story I was telling, only better!

Note that past remarks indicate the euro leaders equate ‘success’ with ‘strong euro’, particularly the ECB, with its single mandate.

So with the euro reacting positively to Draghi’s ‘pledge’, which came after a decline in the euro, more of same is encouraged.

Eurogroup chair sees decisions soon in debt crisis

By Geir Moulson

July 29 (AP) — The German and Italian leaders issued a new pledge to protect the eurozone, while the influential eurogroup chairman was quoted Sunday as saying that officials have no time to lose and will decide in the coming days what measures to take.

The weekend comments capped a string of assurances from European leaders that they will do everything they can to save the 17-nation euro. They came before markets open for a week in which close attention will be focused on Thursday’s monthly meeting of the European Central Bank’s policy-setting governing council.

Last Thursday, ECB President Mario Draghi said the bank would do “whatever it takes” to preserve the euro — and markets surged on hopes of action.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Italian Premier Mario Monti “agreed that Germany and Italy will do everything to protect the eurozone” in a phone conversation Saturday, German government spokesman Georg Streiter said, a statement that was echoed by Monti’s office.

That was nearly identical to a statement issued Friday by Merkel and French President Francois Hollande, which followed Draghi’s comments.

This is from Pavlina’s paper for those of you tracing origins of MMT euro discussion:

Link here.

Notice how in private correspondence Mosler applies the same logic in analyzing the ramifications of the restrictions on deficit spending in the current plan for European Monetary Union:

Operating factors will require reserve adds and drains to keep the system in balance and maintain control of the interbank rate. However, the ECB is able only to act defensively, like all CBs [Central Banks]. It cannot proactively lend Eurosa reserve add, without an offsetting drain. The deficit spending I refer to is needed to offset the need of the private sector to be a net nominal saver in Euros. In the currently proposed system, even the increasing demand for currency in circulation must be accommodated via collateralized loans from the ECB. Net nominal wealth of the system cannot increase. The private sector demand for an increase in net nominal wealth will have to be from the reverse happening at the member nation level. If member nations are restricted from doing this [to deficit spend], a vicious deflationary spiral will result. (Mosler, 1996)

Seems the turning point may have been early June when Trichet made a proposal that included the ECB, as previously discussed.

And note, also as previously discussed, it’s all about ‘the euro’ meaning ‘strong currency.’

So a big relief rally with the solvency issue resolved, and then just the reality of a bad economy, and a too strong euro with no politically correct way to contain it, as dollar buying is ideologically all but impossible.

Also, as previously discussed, member govt deficits seem high enough for modest improvement, absent further aggressive austerity measures.

*MERKEL, HOLLANDE READY TO DO ANYTHING TO PROTECT EURO REG

*GERMAN CHANCELLERY COMMENTS IN E-MAILED STATEMENT

*GERMAN CHANCELLERY COMMENTS ON MERKEL-HOLLANDE TELEPHONE CALL

:(

‘The Dollar Is Going to Go to Hell’: Trump

By Justin Menza

July 17 (CNBC) — The U.S. needs to pay down its debt, and that won’t happen if Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke “goes wild” with more stimulus, Donald Trump told CNBC’s “Squawk Box” on Tuesday.

“The fact is that the country owes $16 trillion, and we just can’t keep doing this,” Trump said. “The dollar is going to go to hell.”

Trump said the artificial Fed stimulus has done nothing, and the only way to get the country back on track is to start paying down debt.

SND Foreign-Currency Holdings Hit Record on Intervention

By Simone Meier

June 7 (Bloomberg) — The Swiss central bank’s foreign- currency reserves surged to a record in May as the euro region’s increasing turmoil forced policy makers to step up their defense of the franc floor. Currency holdings rose to 303.8 billion Swiss francs ($318 billion) at the end of May from 237.6 billion francs in the previous month, according to a statement published on the Swiss National Bank’s website today. Walter Meier, a spokesman at the SNB in Zurich, said by telephone that a “large part” of the increase was due to currency purchases to defend the minimum exchange rate of 1.20 versus the euro.

They have become resigned to the idea that the ECB must write the check for the banking system as do all currency issuers directly or indirectly as previously discussed.

And they now also know the ECB is writing the check for the whole shooting match directly or indirectly also as previously discussed.

With deficits as high as they are and bank and government liquidity sort of there, the euro economy can now muddle through with flattish growth and a large output gap. Ok for stocks and bonds and not so good for people.

Next the action moves to moral hazard risk in an attempt to keep fiscal policies tight without market discipline.

But that’s for another day as first the work on an acceptable framing of the full ECB support they’ve backed into.

Frozen Europe Means ECB Must Resort to ELA

By Dara Doyle and Jeff Black

May 25 (Bloomberg) — The first rule of ELA is you don’t talk about ELA.

The European Central Bank is trying to limit the flow of information about so-called Emergency Liquidity Assistance, which is increasingly being tapped by distressed euro-region financial institutions as the debt crisis worsens. Focus on the program intensified last week after it emerged that the ECB moved some Greek banks out of its regular refinancing operations and onto ELA until they are sufficiently capitalized.

European stocks fell and the euro weakened to a four-month low as investors sought clarity on how the Greek financial system would be kept alive. The episode highlights the ECB’s dilemma as it tries to save banks without taking too much risk onto its own balance sheet. While policy makers argue that secrecy is needed around ELA to prevent panic, the risk is that markets jump to the worst conclusion anyway.

“The lack of transparency is a double-edged sword,” said David Owen, chief European economist at Jefferies Securities International in London. “On the one hand, it increases uncertainty, but at the same time we do not necessarily want to know how bad things are as it can add fuel to the fire.”

Under ELA, the 17 national central banks in the euro area are able to provide emergency liquidity to banks that can’t put up collateral acceptable to the ECB. The risk is borne by the central bank in question, ensuring any losses stay within the country concerned and aren’t shared across all euro members, known as the euro system.

ECB Approval

Each ELA loan requires the assent of the ECB’s 23-member Governing Council and carries a penalty interest rate, though the terms are never made public. Owen estimates that euro-area central banks are currently on the hook for about 150 billion euros ($189 billion) of ELA loans.

The program has been deployed in countries including Germany, Belgium, Ireland and now Greece. An ECB spokesman declined to comment on matters relating to ELA for this article.

The ECB buries information about ELA in its weekly financial statement. While it announced on April 24 that it was harmonizing the disclosure of ELA on the euro system’s balance sheet under “other claims on euro-area credit institutions,” this item contains more than just ELA. It stood at 212.5 billion euros this week, up from 184.7 billion euros three weeks ago.

The ECB has declined to divulge how much of the amount is accounted for by ELA.

Ireland’s Case

Further clues can be found in individual central banks’ balance sheets. In Ireland, home to Europe’s worst banking crisis, the central bank’s claims on euro-area credit institutions, where it now accounts for ELA, stood at 41.3 billion euros on April 27.

Greek banks tapped their central bank for 54 billion euros in January, according to its most recently published figures. That has since risen to about 100 billion euros, the Financial Times reported on May 22, without citing anyone.

Ireland’s central bank said last year it received “formal comfort” from the country’s finance minister that it wouldn’t sustain losses on collateral received from banks in return for ELA.

“If the collateral underpinning the ELA falls short, the government steps in,” said Philip Lane, head of economics at Trinity College Dublin. “Essentially, ELA represents the ECB passing the risk back to the sovereign. That could be the trigger for potential default or, in Greece’s case, potential exit.”

Greek Exit

The prospect of Greece leaving the euro region increased after parties opposed to the terms of the nation’s second international bailout dominated May 6 elections. A new vote will be held on June 17 after politicians failed to form a coalition, and European leaders are now openly discussing the possibility of Greece exiting the euro.

A Greek departure could spark a further flight of deposits from banks in other troubled euro nations, according to UBS AG economists, leaving them more reliant on funding from monetary authorities. Banks in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain saw a decline of 80.6 billion euros, or 3.2 percent, in household and corporate deposits from the end of 2010 through March this year, according to ECB data.

“ELA is a symptom of the strain in the system, and Greece is the tip of the iceberg here,” Owen said. “As concerns mount about break-up, that sparks deposit flight. Suddenly we’re talking about 350 billion, 400 billion as bigger countries avail of ELA.”

German ELA

ELA emerged as part of the euro system’s furniture in 2008, when the global financial crisis led to the bailouts of German property lender Hypo-Real Estate AG and Belgian banking group Dexia. While the Bundesbank’s ELA facility has now been closed, Dexia Chief Executive Officer Pierre Mariani told the bank’s shareholders on May 9 that it continues to access around 12 billion euros of ELA funds.

ELA was a measure that gave central banks more flexibility to keep their banks afloat in situations of short-term stress, said Juergen Michels, chief euro-area economist at Citigroup Global Markets in London.

“It seems to be now a more permanent feature in the periphery countries,” Michels said, adding there’s a risk that “the ECB loses control to some extent over what’s going on.”

The ECB was forced to confirm on May 17 it had moved some Greek banks onto ELA after the news leaked out, roiling financial markets. The ECB said in an e-mail that as soon as the banks are recapitalized, which it expected to happen “soon,” they will regain access to its refinancing operations. The ECB “continues to support Greek banks,” it added.

‘Life Support’

By approving ELA requests, the ECB is ensuring that banks that would otherwise not qualify for its loans have access to liquidity.

“The ELA is a perfect life-support system, but it’s not a system for what happens after that,” said Lorcan Roche Kelly, chief Europe strategist at Trend Macrolytics LLC in Clare, Ireland. “What you need is a bank resolution mechanism, a method to get rid of a bank that’s insolvent. In Ireland, and perhaps in Greece as well, the problem is that you’ve got banking systems that are insolvent.”

For Citigroup chief economist Willem Buiter, there is a bigger issue at stake. ELA breaks a key rule that is designed to bind the monetary union together, he said.

“It constitutes a breach of the principle of one monetary, credit and liquidity policy on uniform terms and conditions for the whole euro system. The existence of ELA undermines the monetary union.”

Interview with The Norwich Bulletin, Oct 6, 2010

US economy muddling through, growing modestly, particularly given the output gap, but growing nonetheless.

Lower crude prices should also help some.

I had guessed the Saudis would hold prices at the $120 Brent level, given their output of just over 10 million bpd showed strong demand

and their capacity to increase to their stated 12.5 million bpd capacity remains suspect. And so with the Seaway pipeline now open (last I heard)

to take crude from Cushing to Brent priced markets I’d guessed WTI would trade up to Brent.

But what has happened is the Saudi oil minister started making noises about lower prices and when ‘market prices’ started selling off the Saudis ‘followed’ by lowering their posted prices, sustaining the myth that they are ‘price takers’ when in reality they are price setters.

So to date, contrary to my prior guess, both wti and brent have sold off quite a bit, and cheaper imported crude is a plus for the US economy. Which is also a plus for the $US, as a lower import bill makes $US ‘harder to get’ for foreigners.

But the trade for quite a while has been strong dollar = weak US stocks due to export pricing/foreign earnings translations, and also because US stocks have weakened on signs of euro zone stress, which has been associated with a weaker euro. So when things seem to be looking up for the euro zone, the euro tends to go up vs the dollar, with US stocks doing better with any sign of ‘improvement’ in the euro zone.

It’s all a tangled case of cross currents, which makes forecasting anything particularly difficult.

Not to mention possible dislocations from the whale, which may or may not have run their course, etc.

And then there’s the news from Greece.

First, they made a full bond payment yesterday of nearly 500 million euro to bond holders who did not accept the PSI discounts. This is confounding for the obvious reasons, signals it sends, moral hazard, credibility, etc. etc. But it’s also a sign the politicians are doing what they think it takes to keep the euro going as the currency of the euro zone. Same goes for the decision to fund Greece as per prior agreements even when there is no Greek govt to talk to, and lots of signs any new govt may not honor the arrangements.

Even if that means tricking private investors out of 100 billion, rewarding those who defy them, whatever. Tactics may be continuously reaching new lows but all for the end of keeping the euro as the single currency.

It also means that while, for example, 10 year Spanish yields may go up or down, the intention is for Spain, one way or another, to fund itself, even if short term. Doesn’t matter.

And more EFSF type discussions. The plan may be to start using those types of funds as needed, keeping the ECB out of it for that much longer, regardless of where longer term bonds happen to trade.

As for the euro zone economy, yes, growth is probably negative, but if they hold off on further fiscal adjustments, the 6%+ deficit they currently are running for the region is probably, at this point, enough to muddle through around the 0 growth neighborhood. The upside isn’t much from there, as with limited private sector credit growth opportunities, and substantial net export growth unlikely, and strong ‘automatic stabilizers’ any growth could be limited by those automatic fiscal stabilizers. Not to mention that this type of optimistic scenario likely strengthens the euro and keeps a lid on net exports as well.

And sad that this ‘bullish scenario’ for the euro zone means their massive output gap doesn’t even begin to close any time soon.

For the US, this bullish scenario has similar limitations, but not quite as severe, so the output gap could start to narrow some and employment as a percentage of the population begin to improve. But only modestly.

The US fiscal cliff is for real, but still far enough away to not be a day to day factor. And it at least does show that fiscal policy does work, at least according to every known forecaster with any credibility, which might open the door to proactive fiscal? Note the increasing chatter about how deficits don’t seem to drive up interest rates? And the increasing chatter about how the US, Japan, UK, etc. aren’t like the euro zone members with regards to interest rates?

Same in the euro zone, where discussion is now common regarding how austerity doesn’t work to grow their economies, with the reason to maintain it now down to the need to restore solvency. This is beginning to mean that if they solved the solvency riddle some other way they might back off on the austerity. And now there is a political imperative to do just that, so things could move in that direction, meaning ECB support for member nation funding, directly or indirectly, which removes the ‘ponzi’ aspect.