Where am I wrong, if at all?

I agree with the political analysis.

I know Bruce Bartlett and he’ll be the first to tell you he does NOT understand monetary operations. Even simple statements like ‘China keeps its dollars in its reserve account at the Fed’ seem to cause him to glass over. He can only repeat headline rhetoric and has no interest in drilling down through it.

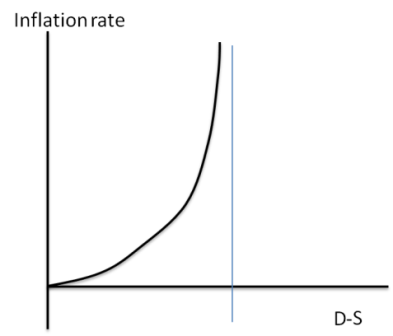

Krugman’s column a week ago, however, may have been a major breakthrough. He conceded the issue of long term deficits was inflation and not solvency. And while his maths and graphs disqualified him from participating in the inflation debate, it so far seems to have shifted the deficit dove position to much firmer ground.

A Congressman might vote to cut Social Security due to fear of Federal insolvency, with all ‘noted’ economists arguing only how far down the road it may be, along with dependence on foreign creditors.

However, I doubt most Congressman would vote to cut Social Security based on some economists predicting possible inflation in 20 years.

So even though Krugman’s reasoning was simply ‘they can always print the money’ followed by highly suspect graphs and statements about how someday that could cause hyper inflation, hopefully it did shift the discussion from solvency to inflation, where it belongs.

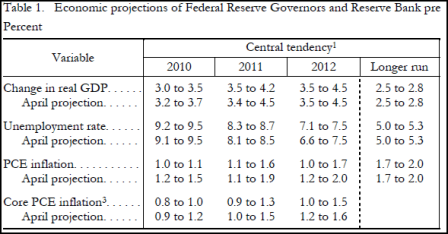

So now the hawk/dove question is, as it should be, whether long term deficits imply long term run away inflation. And while the correct answer is: depends on the offsetting demand leakages/unspent income like pension contributions and other nominal savings desires. Just the fact that the debate shifts away from solvency should be enough for a change of global political attitude.

And, if so, this opens the door to a new era of prosperity as yet unimagined.

By Martin Wolf

July 25 (FT) – The future of fiscal policy was intensely debated in the FT last week. In this Exchange, I want to examine what is going on in the US and, in particular, what is going on inside the Republican party. This matters for the US and, because the US remains the world’s most important economy, it also matters greatly for the world.

My reading of contemporary Republican thinking is that there is no chance of any attempt to arrest adverse long-term fiscal trends should they return to power. Moreover, since the Republicans have no interest in doing anything sensible, the Democrats will gain nothing from trying to do much either. That is the lesson Democrats have to draw from the Clinton era’s successful frugality, which merely gave George W. Bush the opportunity to make massive (irresponsible and unsustainable) tax cuts. In practice, then, nothing will be done.

Indeed, nothing may be done even if a genuine fiscal crisis were to emerge. According to my friend, Bruce Bartlett, a highly informed, if jaundiced, observer, some “conservatives” (in truth, extreme radicals) think a federal default would be an effective way to bring public spending they detest under control. It should be noted, in passing, that a federal default would surely create the biggest financial crisis in world economic history.

To understand modern Republican thinking on fiscal policy, we need to go back to perhaps the most politically brilliant (albeit economically unconvincing) idea in the history of fiscal policy: “supply-side economics”. Supply-side economics liberated conservatives from any need to insist on fiscal rectitude and balanced budgets. Supply-side economics said that one could cut taxes and balance budgets, because incentive effects would generate new activity and so higher revenue.

The political genius of this idea is evident. Supply-side economics transformed Republicans from a minority party into a majority party. It allowed them to promise lower taxes, lower deficits and, in effect, unchanged spending. Why should people not like this combination? Who does not like a free lunch?

How did supply-side economics bring these benefits? First, it allowed conservatives to ignore deficits. They could argue that, whatever the impact of the tax cuts in the short run, they would bring the budget back into balance, in the longer run. Second, the theory gave an economic justification – the argument from incentives – for lowering taxes on politically important supporters. Finally, if deficits did not, in fact, disappear, conservatives could fall back on the “starve the beast” theory: deficits would create a fiscal crisis that would force the government to cut spending and even destroy the hated welfare state.

In this way, the Republicans were transformed from a balanced-budget party to a tax-cutting party. This innovative stance proved highly politically effective, consistently putting the Democrats at a political disadvantage. It also made the Republicans de facto Keynesians in a de facto Keynesian nation. Whatever the rhetoric, I have long considered the US the advanced world’s most Keynesian nation – the one in which government (including the Federal Reserve) is most expected to generate healthy demand at all times, largely because jobs are, in the US, the only safety net for those of working age.

True, the theory that cuts would pay for themselves has proved altogether wrong. That this might well be the case was evident: cutting tax rates from, say, 30 per cent to zero would unambiguously reduce revenue to zero. This is not to argue there were no incentive effects. But they were not large enough to offset the fiscal impact of the cuts (see, on this, Wikipedia and a nice chart from Paul Krugman).

Indeed, Greg Mankiw, no less, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under George W. Bush, has responded to the view that broad-based tax cuts would pay for themselves, as follows: “I did not find such a claim credible, based on the available evidence. I never have, and I still don’t.” Indeed, he has referred to those who believe this as “charlatans and cranks”. Those are his words, not mine, though I agree. They apply, in force, to contemporary Republicans, alas,

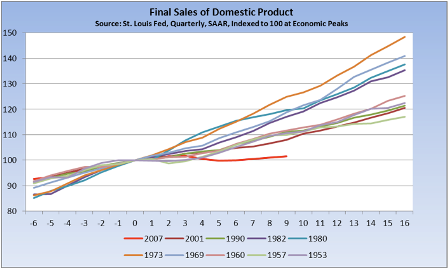

Since the fiscal theory of supply-side economics did not work, the tax-cutting eras of Ronald Reagan and George H. Bush and again of George W. Bush saw very substantial rises in ratios of federal debt to gross domestic product. Under Reagan and the first Bush, the ratio of public debt to GDP went from 33 per cent to 64 per cent. It fell to 57 per cent under Bill Clinton. It then rose to 69 per cent under the second George Bush. Equally, tax cuts in the era of George W. Bush, wars and the economic crisis account for almost all the dire fiscal outlook for the next ten years (see the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities).

Today’s extremely high deficits are also an inheritance from Bush-era tax-and-spending policies and the financial crisis, also, of course, inherited by the present administration. Thus, according to the International Monetary Fund, the impact of discretionary stimulus on the US fiscal deficit amounts to a cumulative total of 4.7 per cent of GDP in 2009 and 2010, while the cumulative deficit over these years is forecast at 23.5 per cent of GDP. In any case, the stimulus was certainly too small, not too large.

The evidence shows, then, that contemporary conservatives (unlike those of old) simply do not think deficits matter, as former vice-president Richard Cheney isreported to have told former treasury secretary Paul O’Neill. But this is not because the supply-side theory of self-financing tax cuts, on which Reagan era tax cuts were justified, has worked, but despite the fact it has not. The faith has outlived its economic (though not its political) rationale.

So, when Republicans assail the deficits under President Obama, are they to be taken seriously? Yes and no. Yes, they are politically interested in blaming Mr Obama for deficits, since all is viewed fair in love and partisan politics. And yes, they are, indeed, rhetorically opposed to deficits created by extra spending (although that did not prevent them from enacting the unfunded prescription drug benefit, under President Bush). But no, it is not deficits themselves that worry Republicans, but rather how they are caused: deficits caused by tax cuts are fine; but spending increases brought in by Democrats are diabolical, unless on the military.

Indeed, this is precisely what John Kyl (Arizona), a senior Republican senator,has just said:

“[Y]ou should never raise taxes in order to cut taxes. Surely Congress has the authority, and it would be right to — if we decide we want to cut taxes to spur the economy, not to have to raise taxes in order to offset those costs. You do need to offset the cost of increased spending, and that’s what Republicans object to. But you should never have to offset the cost of a deliberate decision to reduce tax rates on Americans”

What conclusions should outsiders draw about the likely future of US fiscal policy?

First, if Republicans win the mid-terms in November, as seems likely, they are surely going to come up with huge tax cut proposals (probably well beyond extending the already unaffordable Bush-era tax cuts).

Second, the White House will probably veto these cuts, making itself even more politically unpopular.

Third, some additional fiscal stimulus is, in fact, what the US needs, in the short term, even though across-the-board tax cuts are an extremely inefficient way of providing it.

Fourth, the Republican proposals would not, alas, be short term, but dangerously long term, in their impact.

Finally, with one party indifferent to deficits, provided they are brought about by tax cuts, and the other party relatively fiscally responsible (well, everything is relative, after all), but opposed to spending cuts on core programmes, US fiscal policy is paralysed. I may think the policies of the UK government dangerously austere, but at least it can act.

This is extraordinarily dangerous. The danger does not arise from the fiscal deficits of today, but the attitudes to fiscal policy, over the long run, of one of the two main parties. Those radical conservatives (a small minority, I hope) who want to destroy the credit of the US federal government may succeed. If so, that would be the end of the US era of global dominance. The destruction of fiscal credibility could be the outcome of the policies of the party that considers itself the most patriotic.

In sum, a great deal of trouble lies ahead, for the US and the world.

Where am I wrong, if at all?