The Fed’s plan to maintain a large balance sheet and pay interest on bank reserves is good for financial stability.

By John H. Cochrane

Aug 21 (WSJ) — As Federal Reserve officials lay the groundwork for raising interest rates, they are doing a few things right. They need a little cheering, and a bit more courage of their convictions.

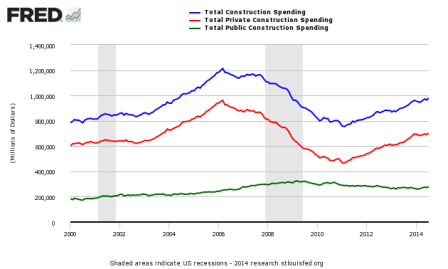

The Fed now has a huge balance sheet. It owns about $4 trillion of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. It owes about $2.7 trillion of reserves (accounts banks have at the Fed), and $1.3 trillion of currency. When it is time to raise interest rates, the Fed will simply raise the interest it pays on reserves. It does not need to soak up those trillions of dollars of reserves by selling trillions of dollars of assets.

Correct!

The Fed’s plan to maintain a large balance sheet and pay interest on bank reserves, begun under former Chairman Ben Bernanke and continued under current Chair Janet Yellen, is highly desirable for a number of reasons—the most important of which is financial stability. Short version: Banks holding lots of reserves don’t go under.

Not true.

Confusing reserves with capital to some extent.

Banks can fail via losses that wipe out capital even with plenty of liquidity.

This policy is new and controversial. However, many arguments against it are based on fallacies. People forget that when the Fed creates a dollar of reserves, it buys a dollar of Treasurys or government-guaranteed mortgage-backed securities. A bank gives the Fed a $1 Treasury, the Fed flips a switch and increases the bank’s reserve account by $1. From this simple fact, it follows that:

• Reserves that pay market interest are not inflationary. Period. Now that banks have trillions more reserves than they need to satisfy regulations or service their deposits, banks don’t care if they hold another dollar of interest-paying reserves or another dollar of Treasurys. They are perfect substitutes at the margin. Exchanging red M&Ms for green M&Ms does not help your diet. Commenters have seen the astonishing rise in reserves—from $50 billion in 2007 to $2.7 trillion today—and warned of hyperinflation to come. This is simply wrong as long as reserves pay market interest.

Yes and no.

Yes, the mix of Fed liabilities per se isn’t inflationary.

No, even if they didn’t pay interest it wouldn’t be inflationary. In fact, it would mean a reduction in govt interest payments which is a contractionary bias.

And his point is best stated by stating that both reserves and tsy secs are simply dollar denominated ‘bank accounts’ at the Fed, the difference being the duration and rates, directly or indirectly selected by ‘govt’.

• Large reserves also aren’t deflationary. Reserves are not “soaking up money that could be lent.” The Fed is not “paying banks not to lend out the money” and therefore “starving the economy of investment.”

True.

Every dollar invested in reserves is a dollar that used to be invested in a Treasury bill.

Wrong statement of support. He should state that the causation goes from loans to deposits. ‘Loanable funds’ applies to fixed fx, not floating fx.

A large Fed balance sheet has no effect on funds available for investment.

True, they are infinite in any case. Bank lending is constrained only in the short term by capital, as there is always infinite capital available with time at a price that gets reflected in lending charges.

• The Fed is not “subsidizing banks” by paying interest on reserves.

It is to the extent that paying interest is subsidizing the economy in general, as govt is a net payer of interest.

The interest that the Fed will pay on reserves will come from the interest it receives on its Treasury securities.

Sort of. Better said that the interest received on the tsy’s will equal/exceed/etc. the interest paid on reserves. ‘Come from’ is a poor choice of words.

If the Fed sold its government securities to banks, those banks would be getting the same interest directly from the Treasury.

True.

The Fed has started a “reverse repurchase” program that will allow nonbank financial institutions effectively to have interest-paying reserves. This program was instituted to allow higher interest rates to spread more quickly through the economy.

True.

Again, I see a larger benefit in financial stability. The demand for safe, interest-paying money expressed so far in overnight repurchase agreements, short-term commercial paper, auction-rate securities and other vehicles that exploded in the financial crisis can all be met by interest-paying reserves.

Sort of. The term structure of rates constantly adjusts to indifference levels is how I’d say it.

Encouraging this switch is the keystone to avoiding another crisis. The Treasury should also offer fixed-value floating-rate electronically transferable debt.

Why??? Indexed to what? The one’s they are doing indexed to T bills make no logical sense at all.

This Fed reverse-repo program spawns many unfounded fears, even at the Fed. The July minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee revealed participants worried that “in times of financial stress, the facility’s counterparties could shift investments toward the facility and away from financial and nonfinancial corporations.”

This fear forgets basic accounting.

True.

The Fed controls the quantity of reserves. Reserves can only expand if the Fed chooses to buy assets—which is exactly what the Fed does in financial crises.

Furthermore, this fear forgets that investors who want the safety of Treasurys can buy them directly. Or they can put money in banks that in turn can hold reserves. The existence of the Fed’s program has minuscule effects on investors’ options in a crisis. Interest-paying reserves are just a money-market fund 100% invested in Treasurys with a great electronic payment mechanism.

Available to banks.

That’s exactly what we should encourage for financial stability.

The Open Market Committee minutes also said that, “Participants noted that a relatively large [repurchase] facility had the potential to expand the Federal Reserve’s role in financial intermediation and reshape the financial industry.”

Not really.

It always has been about offsetting operating factors one functionally identical way or another.

Yes, and that’s a feature not a bug. The financial industry failed and the Fed is reshaping it under the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial-reform law. Allowing money previously invested in run-prone shadow banking to be invested in 100%-safe reserves is the best thing the Fed could do to reshape the industry.

They can only do that if they reduce the institutional additions to the bank’s cost of funds/lower risk restrictions to make the banks more competitive with non bank lenders.

Temptations remain. For example, with trillions of reserves in excess of regulatory reserve requirements, the Fed loses what was left of its control over bank lending and deposit creation. The Fed will be tempted to use direct regulation and capital ratios to try to micromanage lending.

That’s all it ever had. Lending was never reserve constrained.

It should not. The big balance sheet is a temptation for the Fed to buy all sorts of assets other than short-term Treasurys, and to meddle in many markets, as it is already supporting the mortgage market. It should not.

I see precious little difference apart from option vol considerations.

The Fed is making no promises about the stability of these arrangements—a large balance sheet and market interest on reserves available to non-banks. It should. In particular, it should clarify whether it will allow its balance sheet to shrink as long-term assets run off, or reinvest the proceeds as I would prefer.

It doesn’t matter for what he’s talking about.

Most of the financial stability benefits only occur if these arrangements are permanent and market participants know it. We can debate whether interest rate policy should follow rules or discretion, be predictable or adapt to each day’s Fed desire. But the basic structures and institutions of monetary policy should be firm rules.

The remaining short-term question is when to raise rates. Ms. Yellen has already made an important decision: The Fed will not, for now, use interest-rate policy for “macroprudential” tinkering. This too is wise. We learned in the last crisis that the Fed is only composed of smart human beings. They are not clairvoyant and cannot tell a “bubble” from a boom in real time any better than the banks and hedge funds betting their own money on the difference. Manipulating interest rates to stabilize inflation is hard enough. Stabilizing inflation and unemployment is harder still.

Especially when they have it backwards.

Additionally chasing will-o-wisp “bubbles,” “imbalances” and “crowded trades” will only lead to greater macroeconomic and financial instability.

Here too a firm commitment would help. Otherwise market participants will be constantly looking over their shoulders for the Fed to start meddling in home and asset prices.

Plenty of uncertainties, challenges and temptations remain. Tomorrow, we can go back to investigating, arguing and complaining. Today let’s cheer a few big things done right.

Mr. Cochrane is a professor of finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, and an adjunct scholar at the Cato Institute.

Doesn’t mention/forgets that the Fed buying secs is functionally identical to the tsy not selling them in the first place, etc.