By David Stockman

July 31 (NYT) — If there were such a thing as Chapter 11 for politicians, the Republican push to extend the unaffordable Bush tax cuts would amount to a bankruptcy filing. The nation’s public debt — if honestly reckoned to include municipal bonds and the $7 trillion of new deficits baked into the cake through 2015 — will soon reach $18 trillion. That’s a Greece-scale 120 percent of gross domestic product, and fairly screams out for austerity and sacrifice. It is therefore unseemly for the Senate minority leader, Mitch McConnell, to insist that the nation’s wealthiest taxpayers be spared even a three-percentage-point rate increase.

Yet another ‘expert’ with fear mongering with ‘the US is the next Greece’ nonsense. So much for whatever positives may be left of his legacy.

More fundamentally, Mr. McConnell’s stand puts the lie to the Republican pretense that its new monetarist and supply-side doctrines are rooted in its traditional financial philosophy. Republicans used to believe that prosperity depended upon the regular balancing of accounts — in government, in international trade, on the ledgers of central banks and in the financial affairs of private households and businesses, too. But the new catechism, as practiced by Republican policymakers for decades now, has amounted to little more than money printing and deficit finance — vulgar Keynesianism robed in the ideological vestments of the prosperous classes.

At least they are practical enough to add to aggregate demand when needed.

Does anyone think there is an excess of demand that calls for a tax hike?

Any call for a tax hike on ‘fairness’ should be ‘paid for’ with at least an offsetting tax cut somewhere.

This approach has not simply made a mockery of traditional party ideals. It has also led to the serial financial bubbles and Wall Street depredations that have crippled our economy. More specifically, the new policy doctrines have caused four great deformations of the national economy, and modern Republicans have turned a blind eye to each one. The first of these started when the Nixon administration defaulted on American obligations under the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement to balance our accounts with the world. Now, since we have lived beyond our means as a nation for nearly 40 years, our cumulative current-account deficit — the combined shortfall on our trade in goods, services and income — has reached nearly $8 trillion. That’s borrowed prosperity on an epic scale.

That’s been adding to our real terms of trade and standard of living on an epic scale, and, ironically, the rest of the world is fighting to continue it while we are pressing to end it. Go figure!

It is also an outcome that Milton Friedman said could never happen when, in 1971, he persuaded President Nixon to unleash on the world paper dollars no longer redeemable in gold or other fixed monetary reserves. Just let the free market set currency exchange rates, he said, and trade deficits will self-correct.

He was right. It continuously self corrects to reflect rest of world savings desires of $US financial assets.

It may be true that governments, because they intervene in foreign exchange markets, have never completely allowed their currencies to float freely. But that does not absolve Friedman’s $8 trillion error. Once relieved of the discipline of defending a fixed value for their currencies, politicians the world over were free to cheapen their money and disregard their neighbors.

Yes, to our advantage!

In fact, since chronic current-account deficits result from a nation spending more than it earns, stringent domestic belt-tightening is the only cure.

Leave it to Dave to promote a cure for prosperity.

When the dollar was tied to fixed exchange rates, politicians were willing to administer the needed castor oil, because the alternative was to make up for the trade shortfall by paying out reserves, and this would cause immediate economic pain — from high interest rates, for example. But now there is no discipline, only global monetary chaos as foreign central banks run their own printing presses at ever faster speeds to sop up the tidal wave of dollars coming from the Federal Reserve.

It’s not from the Fed, Dave, it’s from the Treasury deficit spending and private deficit spending.

The second unhappy change in the American economy has been the extraordinary growth of our public debt. In 1970 it was just 40 percent of gross domestic product, or about $425 billion. When it reaches $18 trillion, it will be 40 times greater than in 1970. This debt explosion has resulted not from big spending by the Democrats, but instead the Republican Party’s embrace, about three decades ago, of the insidious doctrine that deficits don’t matter if they result from tax cuts.

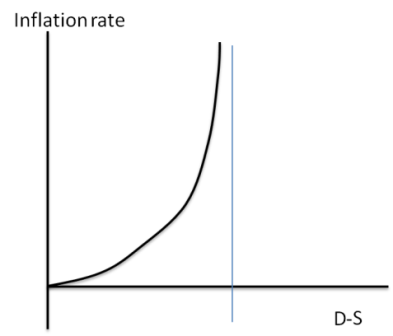

Public sector deficits = non govt savings of those financial assets. And the unemployment rate and inflation rate are telling us federal deficits are too small to provide the savings demanded by the rest of us.

In 1981, traditional Republicans supported tax cuts, matched by spending cuts, to offset the way inflation was pushing many taxpayers into higher brackets and to spur investment. The Reagan administration’s hastily prepared fiscal blueprint, however, was no match for the primordial forces — the welfare state and the warfare state — that drive the federal spending machine. Soon, the neocons were pushing the military budget skyward. And the Republicans on Capitol Hill who were supposed to cut spending exempted from the knife most of the domestic budget — entitlements, farm subsidies, education, water projects. But in the end it was a new cadre of ideological tax-cutters who killed the Republicans’ fiscal religion.

And over the next 10 years inflation came down from over 12% to 3%, even with all the deficit spending because savings desires were even higher, and continue to grow geometrically due to tax advantaged pension contributions, etc.

Through the 1984 election, the old guard earnestly tried to control the deficit, rolling back about 40 percent of the original Reagan tax cuts. But when, in the following years, the Federal Reserve chairman, Paul Volcker, finally crushed inflation,

Volcker did not crush inflation. If anything, his high rates added to business costs and unearned income long after inflation turned down due to positive supply shocks in the energy markets, helped by the dereg of natural gas in 1978 that did the lion’s share of cutting the demand for crude for electricity generation.

enabling a solid economic rebound, the new tax-cutters not only claimed victory for their supply-side strategy but hooked Republicans for good on the delusion that the economy will outgrow the deficit if plied with enough tax cuts. By fiscal year 2009, the tax-cutters had reduced federal revenues to 15 percent of gross domestic product, lower than they had been since the 1940s. Then, after rarely vetoing a budget bill and engaging in two unfinanced foreign military adventures, George W. Bush surrendered on domestic spending cuts, too — signing into law $420 billion in non-defense appropriations, a 65 percent gain from the $260 billion he had inherited eight years earlier. Republicans thus joined the Democrats in a shameless embrace of a free-lunch fiscal policy.

Not my first choice for Federal spending, but certainly did the trick of turning the economy in 2003.

The third ominous change in the American economy has been the vast, unproductive expansion of our financial sector. Here, Republicans have been oblivious to the grave danger of flooding financial markets with freely printed money and, at the same time, removing traditional restrictions on leverage and speculation. As a result, the combined assets of conventional banks and the so-called shadow banking system (including investment banks and finance companies) grew from a mere $500 billion in 1970 to $30 trillion by September 2008.

The real problem with the financial sector is that it preys on the real economy with both a massive brain drain and a drain of other real resources as well.

But the trillion-dollar conglomerates that inhabit this new financial world are not free enterprises. They are rather wards of the state, extracting billions from the economy with a lot of pointless speculation in stocks, bonds, commodities and derivatives. They could never have survived, much less thrived, if their deposits had not been government-guaranteed and if they hadn’t been able to obtain virtually free money from the Fed’s discount window to cover their bad bets.

They didn’t get free money to cover their bad debts. All losses were deducted from shareholder value. Some banks lost all shareholder funds and were liquidated or sold (with the FDIC realizing losses after the shareholders were wiped out)

Functionally, tarp was regulatory forbearance, not a federal expenditure.

The fourth destructive change has been the hollowing out of the larger American economy. Having lived beyond our means for decades by borrowing heavily from abroad, we have steadily sent jobs and production offshore. In the past decade, the number of high-value jobs in goods production and in service categories like trade, transportation, information technology and the professions has shrunk by 12 percent, to 68 million from 77 million. The only reason we have not experienced a severe reduction in nonfarm payrolls since 2000 is that there has been a gain in low-paying, often part-time positions in places like bars, hotels and nursing homes.

Not true. The trade deficit is an enormous benefit. For a given size govt, it allows for lower taxes/higher deficits so Americans can have enough spending power to buy both all we can produce at full employment plus whatever the rest of the world wants to sell us. In 1999/2000, unemployment fell below 3.8%, even as the trade deficit soared to $380 billion.

It is not surprising, then, that during the last bubble (from 2002 to 2006) the top 1 percent of Americans — paid mainly from the Wall Street casino — received two-thirds of the gain in national income, while the bottom 90 percent — mainly dependent on Main Street’s shrinking economy — got only 12 percent. This growing wealth gap is not the market’s fault. It’s the decaying fruit of bad economic policy.

Agreed!!! However this has nothing to do with the rest of what he’s been droning on about. In fact, higher deficits are usually result in stronger economies which are associated with lower income inequality.

The day of national reckoning has arrived. We will not have a conventional business recovery now, but rather a long hangover of debt liquidation and downsizing — as suggested by last week’s news that the national economy grew at an anemic annual rate of 2.4 percent in the second quarter. Under these circumstances, it’s a pity that the modern Republican Party offers the American people an irrelevant platform of recycled Keynesianism when the old approach — balanced budgets, sound money and financial discipline — is needed more than ever.

No, we need a full payroll tax holiday, $500 per capita revenue sharing for the states, and an $8 transition job for anyone willing and able to work.

David Stockman, a director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan, is working on a book about the financial crisis.