The way I read it, he’s agreed that it’s about inflation, not solvency.

That is, in ratings agency speak, willingness to pay could be an issue, but not ability to pay.

That’s enough for me to declare victory on that key issue, and move on.

Not that I at all agree with his descriptions of monetary operations or his ‘inflation channels.’ I just see no reason to rehash all that and risk loss of focus on the larger point he’s conceded.

This reads like a true breakthrough. Hopefully this opens the flood gates and the remaining deficit doves pile on, and July 17, 2010 is remembered as the day MMT broke through and turned the tide.

And in the real world it’s all about celebrity status.

With Jamie’s credentials and definitive response to the sustainability commission, Paul finally had a sufficiently ‘worthy’ advocate which gave him the opening to respond and concede.

I Would Do Anything For Stimulus, But I Won’t Do That (Wonkish)By Paul Krugman

It’s really not relevant to current policy debates, but there’s an issue that’s been nagging at me, so I thought I’d write it up.

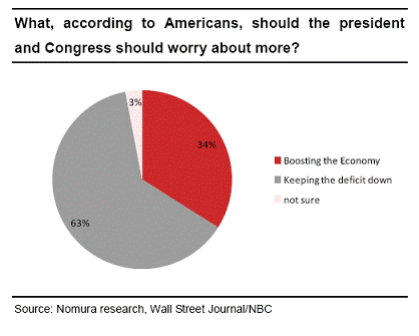

Right now, the real policy debate is whether we need fiscal austerity even with the economy deeply depressed. Obviously, I’m very much opposed — my view is that running deficits now is entirely appropriate.

But here’s the thing: there’s a school of thought which says that deficits arenever a problem, as long as a country can issue its own currency. The most prominent advocate of this view is probably Jamie Galbraith, but he’s not alone.

Now, Jamie and I are, I think, in complete agreement about what we should be doing now. So we’re talking theory, not practice. But I can’t go along with his view that

So long as U.S. banks are required to accept U.S. government checks — which is to say so long as the Republic exists — then the government can and does spend without borrowing, if it chooses to do so … Insolvency, bankruptcy, or even higher real interest rates are not among the actual risks to this system.

OK, I don’t think that’s right. To spend, the government must persuade the private sector to release real resources. It can do this by collecting taxes, borrowing, or collecting seignorage by printing money. And there are limits to all three. Even a country with its own fiat currency can go bankrupt, if it tries hard enough.

How does that work? A bit of modeling under the fold.

Let’s think in terms of a two-period model, although I won’t need to say much about the first period. In period 1, the government borrows, issuing indexed bonds (I could make them nominal, but then I’d need to introduce expectations about inflation, and we’ll end up in the same place.) This means that in period 2 the government owes real debt service in the amount D.

The government may meet this debt service requirement, in whole or in part, by running a primary surplus, an excess of revenue over current spending. Let’s suppose, however, that there’s an upper limit S to the feasible primary surplus — a limit imposed by political constraints, administrative issues (if taxes are too high everyone will evade), or the sheer fact that tax collections can’t exceed GDP.

But the government also has a printing press. The real revenue it collects by using this press is [M(t) – M(t-1)]/P(t), where M is the money supply and P the price level.

What determines the price level? Let’s assume a simple quantity theory, with the price level proportional to the money supply:

P(t) = V*M(t)

By assuming this, I’m actually making the most favorable assumption about the power of seignorage, since in practice, running the printing presses leads to a fall in the real demand for money (people start using lumps of coal or whatever as substitutes.)

OK, now let’s ask what happens if the government has run up enough debt that the upper limit on the primary surplus is a binding constraint, and it’s necessary to run the printing presses to make up the difference. In that case,

[M(t) – M(t-1)]/P(t) = D – S

But P is proportional to M, so this becomes

[M(t) – M(t-1)]/VM(t) = D – S

Rearrange a bit, and we have

M(t)/M(t-1) = 1/[1 – V[D-S]]

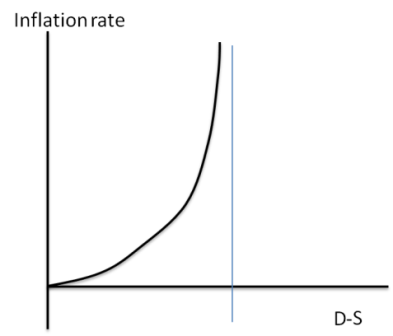

And what does this imply? Since the price level is, by assumption, proportional to M, this tells us that the higher the debt burden, the higher the required rate of inflation — and, crucially, that as D-S heads toward a critical level, this implied inflation heads off to infinity. That is, it looks like this:

So there is a maximum level of debt you can handle. In practice, if it makes sense to say such a thing with regard to a stylized model, at some point lower than the critical level implied by this model the government would decide that default was a better option than hyperinflation.

And going back to period 1, lenders would take this possibility into account. So there are real limits to deficits, even in countries that can print their own currency.

Now, I’m sure I’m about to get comments and/or responses on other blogs along the lines of “Ha! So now Krugman admits that deficits cause hyperinflation! Peter Schiff roolz” Um, no — in extreme conditions they CAN cause hyperinflation; we’re nowhere near those conditions now. All I’m saying here is that I’m not prepared to go as far as Jamie Galbraith. Deficits can cause a crisis; but that’s no reason to skimp on spending right now.