Forget the ‘fiscal cliff’

By Stephanie Kelton

Dec 21 (LA Times) — Look, up in the sky! It’s a “fiscal cliff.” It’s a slope. It’s an obstacle course.

The truth is, it doesn’t really matter what we call it. It only matters what it is: a lamebrained package of economic depressants bearing down on a lame-duck Congress.

This hastily concocted mix of across-the-board spending cuts and tax increases for all was supposed to force Congress to get serious about dealing with our nation’s debt and deficit. The question everyone’s asking is this: On whose backs should we balance the federal budget? One side wants higher taxes; the other wants spending cuts. And while that debate rages, the right question is being ignored: Why are we worried about balancing the federal budget at all?

You read that right. We may strive to balance our work and leisure time and to eat a balanced diet. Our Constitution enshrines the principle of balance among our three branches of government. And when it comes to our personal finances, we know that the family checkbook must balance.

So when we hear that the federal government hasn’t balanced its books in more than a decade, it seems sensible to demand a return to that kind of balance in Washington as well. But that would actually be a huge mistake.

History tells the tale. The federal government has achieved fiscal balance (even surpluses) in just seven periods since 1776, bringing in enough revenue to cover all of its spending during 1817-21, 1823-36, 1852-57, 1867-73, 1880-93, 1920-30 and 1998-2001. We have also experienced six depressions. They began in 1819, 1837, 1857, 1873, 1893 and 1929.

Do you see the correlation? The one exception to this pattern occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the dot-com and housing bubbles fueled a consumption binge that delayed the harmful effects of the Clinton surpluses until the Great Recession of 2007-09.

Why does something that sounds like good economics balancing the budget and paying down debt end up harming the economy? The answers may surprise you.

Spending is the lifeblood of our economy. Without it, there would be no sales, and without sales, no profits and no reason for any private firm to produce anything for the marketplace. We tend to forget that one person’s spending becomes another person’s income. At its most basic level, macroeconomics teaches that spending creates income, income creates sales and sales create jobs.

And creating jobs is what we need to do. Until the fiscal cliff distracted us, we all understood that. Today, we have roughly 3.4 people competing for every available job in America. The unemployment rate is like a macroeconomic thermometer when it registers a high rate, it’s an indication that the deficit is too small.

So in our current circumstance a growing but fragile economy policymakers are wrong to focus on the fact that there is a deficit. It’s just a symptom. Instituting tax increases and spending cuts will pull the rug out from under consumers, thereby disrupting the income-sales-jobs relationship. Slashing trillions from the deficit will only depress spending for year to come, worsening unemployment and setting back economic growth.

Conveying this is an uphill battle. The public has been badly misinformed. We do not have a debt crisis, and our deficit is not a national disgrace. We are not at the mercy of the Chinese, and we’re in no danger of becoming Greece. That’s because the U.S. government is not like a household, or a private business, or a municipality, or a country in the Eurozone. Those entities are all users of currency; the U.S. government is an issuer of currency. It can never run out of its own money or face the kinds of problems we face when our books don’t balance.

The effort to balance the books that’s at the heart of the fiscal cliff is simply misguided. Instead of butting heads over whose taxes to raise and which programs to cut, lawmakers should be haggling over how to use the tool of a federal deficit to boost incomes, employment and growth. That’s the balancing act we need.

Stephanie Kelton is an associate professor of economics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and the founder and editor of New Economic Perspectives. @deficitowl

Category Archives: Employment

Stephanie Kelton on Modern Monetary Theory’s Goals for Full Employment and Government Deficits

Cliff notes

Jobless Claims Fell More Than Expected, Down by 25,000 to 370,000

I haven’t written much this week because I haven’t seen much to write about.

Still looks like both the economy and the markets are discounting the cliff. And still looks to me like ex cliff GDP would be growing at about 4% this quarter, with the Sandy-cliff related cutbacks keeping that down to maybe 2.5%. And going over the full cliff is taking off maybe 2% more, leaving GDP modestly positive.

Which is what stocks and bonds seem to be fully discounting.

As previously discussed, the housing cycle seems to have turned up, which looks to be an extended, multi year upturn with a massive ‘housing output gap’ to be filled. And employment is modestly improving as well, also with a large output gap to fill. Car sales are back over 15 million, and also with a large output gap to fill.

The way I see the politics unfolding, the full cliff will be avoided, if not in advance shortly afterwards, as fully discussed to a fault by the media. That means GDP growth head back towards 4% (and maybe more)

Nor do I see anything catastrophic happening in the euro zone. They continue to ‘do what it takes’ to keep everyone funded and away from default. And conditionality means continued weakness. Q3 GDP was down .1%, a modest improvement from down .2% in Q2, and a flat Q4 wouldn’t surprise me. The rising deficits from ‘automatic fiscal stabilizers’ (rising transfer payments and falling revenues) have increased deficits to the point where they can sustain what’s left of demand. And the recent report of German exports to the euro zone rising at 3.5% maybe indicating that the overall support for GDP will continue to come disproportionately from Germany. And rising net exports from the euro zone will continue to cause the euro to firm to the point of ‘rebalance’ which should mean a much firmer euro. And as part of that story, Japan may be buying euro to support it’s exports to the euro zone, as per the prior ‘Trojan Horse’ discussions, and as evidenced by the yen weakening vs the euro, also as previously discussed.

And you’d think with every forecaster telling the politicians that tax hikes and spending cuts- deficit reduction- causing GDP to be revised down and unemployment up, and the reverse- tax cuts and spending hikes causing upward GDP revisions and lower unemployment- they’d finally figure this thing out and act accordingly?

Probably not…

UK Future Jobs Fund vindicated

Helps support the idea that an employed labor buffer stock works a lot better than an unemployed labor buffer stock, much like we’ve been suggesting for the last two decades:

Future Jobs Fund vindicated

By Tanweer Ali

November 27 — Last week the government finally published its impact report on Labour’s Future Jobs Fund. According to the report, two years after starting their jobs with the scheme, participants were 16 per cent less likely to be on benefits than if they had not taken part and 27 per cent more likely to be in unsubsidised employment. The net benefit to society of the scheme was £7,750 per participant, after accounting for a net cost of £3,100 to the Treasury . Not bad for a scheme condemned as a failure by the current government, and certainly better than anything that replaced it.

The Future Jobs Fund was introduced in 2009 to address the problem of long-term youth unemployment. About 100,000 people in the 18-24 age group out of work for a year or more were guaranteed a job for six months. Later the threshold was reduced to six months. An additional 50,000 guaranteed jobs were available for people of all ages in selected unemployment hotspots.

The idea of addressing long-term unemployment through job guarantees is not new. A number of such schemes were created in Depression-era America, putting young people to work in the National Parks, among other places. An economic rationale was provided by the economist Hyman Minsky. Many schemes for the unemployed focus on skills, and making people more employable, but don’t address the lack of demand for labour. Especially in times of recession and economic stagnation, the big problem is that there simply aren’t enough private sector jobs to go around. Minsky’s solution was for the state to act, in his terminology as ‘employer of last resort’, and provide work at the minimum wage (though I’d prefer to see people paid a living wage). This way the state is not competing with the private sector, merely providing a buffer in hard times.

Direct job creation schemes fell out of favour in the 1970s and 1980s, and the focus shifted to other active labour market policies. Poorly designed job creation programmes are beset by a number of serious problems. The FJF was designed after a careful study of the failure of earlier schemes, drawing on best practices from around the world, and ironing out potential faults. The scheme provided real jobs, not workfare, which created real benefits in the community, paid at the national minimum wage, with time off to look for other, unsubsidised jobs. It seems that the current government never understood the idea of transitional jobs. Anyway it was Labour’s idea, so it must have been bad, right?

Job guarantees have big advantages. For building confidence and job-readiness it’s hard to beat – the best way to prepare people for the job market is to give them a job. It is also visibly fair. Rather than leaving people idle, we are deploying our nation’s key resource in carrying out important work, be it caring in the community, working in schools, or preserving the environment. Also, boosting the incomes of people who would otherwise be unemployed constitutes a highly economic effective stimulus, one that, at a relatively low wage level, is unlikely to be inflationary. Finally, such a scheme will be cost-effective. A job guarantee is a more efficient use of money than other, broader stimulus schemes, as it is specifically targeted at a clear objective. The job guarantee is cheap for what it can achieve, far from being unaffordable.

Labour should be proud of the FJF and of its 2010 manifesto pledge to extend it to all adults out of work for two years or more. Now that the FJF has been vindicated, it’s time to reaffirm our commitment to a job guarantee, and make it a central part of a full employment policy. A robust job guarantee, once turned into an enduring institution, may not be a silver bullet for all our problems, but will go some way to addressing the misery and waste of long-term unemployment, in this downturn and in future recessions.

Keynes 1939 radio address

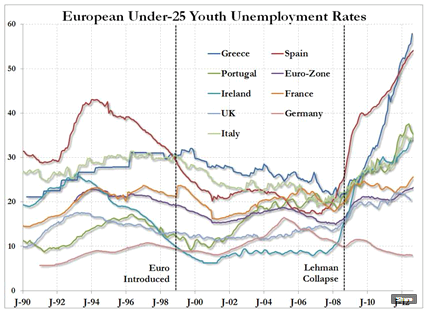

European Under-25 Youth Unemployment Rates

7DIF video

SCE Number 1!!!

Sweden Pays Jobless Youth to Move to Norway

Sweden Pays Jobless Youth to Move to Norway

November 1 (Telegraph) — A Swedish town has taken to paying people to look for work in Norway in an attempt to reduce soaring youth unemployment.

Under a scheme organised by the local authorities in the town of Soderhamn and by Sweden’s national employment office, anyone aged between 18 and 28 can volunteer to take a “Job Journey” to Oslo and attempt track down gainful employment.

Those who sign up get a ticket to the Norwegian capital and are put up in an Oslo youth hostel for a month, with Soderhamn council picking up the 20 a night bill. The package also includes on-the-spot guidance on how to get a job in Sweden’s northern neighbour.

“We had an unemployment rate of over 25 per cent, so we had to find solutions,” Magus Nilsen, the man in charge of the project at Soderhamn council, told the Daily Telegraph. “Going to Norway to find work has always been quite popular with young people, but sometimes they want to go but don’t know how to find a job or accommodation so we thought we’d give them a bit of help with both.”

So far around 100 people have decided to leave Soderhamn, a town of 12,000, 250 kilometres due north of Stockholm, to try their luck in the bright lights of Oslo, and some, at least, have struck gold.

After two years on the dole in his hometown Andreas Larsson opted for a “Job Journey” to Norway and now works as a lorry driver in Oslo.

“I came here on a Thursday and on Monday morning I had a job, so it was fast,” he told Swedish Radio. “It almost felt a bit unreal, as if you have come to the promised land.”