Chairman Ben S. Bernanke

November 19, 2010

The global economy is now well into its second year of recovery from the deep recession triggered by the most devastating financial crisis since the Great Depression. In the most intense phase of the crisis, as a financial conflagration threatened to engulf the global economy, policymakers in both advanced and emerging market economies found themselves confronting common challenges. Amid this shared sense of urgency, national policy responses were forceful, timely, and mutually reinforcing. This policy collaboration was essential in averting a much deeper global economic contraction and providing a foundation for renewed stability and growth.

The main policy response as the automatic fiscal stabilizers that, fortunately were in place to cut govt revenues and increase transfer payments, automatically raising the federal deficit to levels where it added sufficient income and savings of financial assets to support aggregate demand at current levels. And while the contents selected weren’t my first choice, the fiscal stimulus package added some support as well.

In recent months, however, that sense of common purpose has waned. Tensions among nations over economic policies have emerged and intensified, potentially threatening our ability to find global solutions to global problems. One source of these tensions has been the bifurcated nature of the global economic recovery: Some economies have fully recouped their losses

Those who have sustained adequate domestic aggregate demand through appropriate fiscal policy.

while others have lagged behind.

Those who have not had adequate fiscal responses.

But at a deeper level, the tensions arise from the lack of an agreed-upon framework to ensure that national policies take appropriate account of interdependencies across countries and the interests of the international system as a whole. Accordingly, the essential challenge for policymakers around the world is to work together to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome–namely, a robust global economic expansion that is balanced, sustainable, and less prone to crises.

Unfortunately, that would require an understanding of monetary operations and that a currency is a (simple) public monopoly. And with that comes the understanding that the us, for example, is far better off going it alone.

The Two-Speed Global Recovery

International policy cooperation is especially difficult now because of the two-speed nature of the global recovery. Specifically, as shown in figure 1, since the recovery began, economic growth in the emerging market economies (the dashed blue line) has far outstripped growth in the advanced economies (the solid red line). These differences are partially attributable to longer-term differences in growth potential between the two groups of countries, but to a significant extent they also reflect the relatively weak pace of recovery thus far in the advanced economies. This point is illustrated by figure 2, which shows the levels, as opposed to the growth rates, of real gross domestic product (GDP) for the two groups of countries. As you can see, generally speaking, output in the advanced economies has not returned to the levels prevailing before the crisis, and real GDP in these economies remains far below the levels implied by pre-crisis trends. In contrast, economic activity in the emerging market economies has not only fully made up the losses induced by the global recession, but is also rapidly approaching its pre-crisis trend. To cite some illustrative numbers, if we were to extend forward from the end of 2007 the 10-year trends in output for the two groups of countries, we would find that the level of output in the advanced economies is currently about 8 percent below its longer-term trend, whereas economic activity in the emerging markets is only about 1-1/2 percent below the corresponding (but much steeper) trend line for that group of countries. Indeed, for some emerging market economies, the crisis appears to have left little lasting imprint on growth. Notably, since the beginning of 2005, real output has risen more than 70 percent in China and about 55 percent in India.

No mention of the size of the budget deficits in those nations, not forgetting to include lending by state owned institutions that is, functionally, deficit spending.

In the United States, the recession officially ended in mid-2009, and–as shown in figure 3–real GDP growth was reasonably strong in the fourth quarter of 2009 and the first quarter of this year.

Mainly a bounce from an oversold inventory position due to the prior fear mongering and real risks of systemic failure.

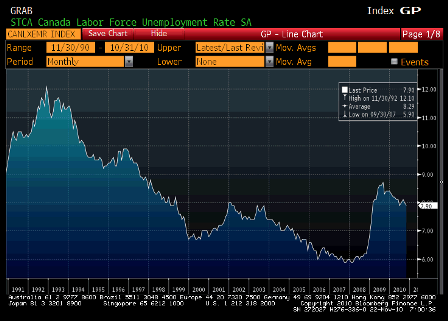

However, much of that growth appears to have stemmed from transitory factors, including inventory adjustments and fiscal stimulus. Since the second quarter of this year, GDP growth has moderated to around 2 percent at an annual rate, less than the Federal Reserve’s estimates of U.S. potential growth and insufficient to meaningfully reduce unemployment. And indeed, as figure 4 shows, the U.S. unemployment rate (the solid black line) has stagnated for about eighteen months near 10 percent of the labor force, up from about 5 percent before the crisis; the increase of 5 percentage points in the U.S. unemployment rate is roughly double that seen in the euro area, the United Kingdom, Japan, or Canada. Of some 8.4 million U.S. jobs lost between the peak of the expansion and the end of 2009, only about 900,000 have been restored thus far. Of course, the jobs gap is presumably even larger if one takes into account the natural increase in the size of the working age population over the past three years.

Of particular concern is the substantial increase in the share of unemployed workers who have been without work for six months or more (the dashed red line in figure 4). Long-term unemployment not only imposes extreme hardship on jobless people and their families, but, by eroding these workers’ skills and weakening their attachment to the labor force, it may also convert what might otherwise be temporary cyclical unemployment into much more intractable long-term structural unemployment. In addition, persistently high unemployment, through its adverse effects on household income and confidence, could threaten the strength and sustainability of the recovery.

Low rates of resource utilization in the United States are creating disinflationary pressures. As shown in figure 5, various measures of underlying inflation have been trending downward and are currently around 1 percent, which is below the rate of 2 percent or a bit less that most Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) participants judge as being most consistent with the Federal Reserve’s policy objectives in the long run.1 With inflation expectations stable, and with levels of resource slack expected to remain high, inflation trends are expected to be quite subdued for some time.

Yes, the FOMC continues to fear deflation.

Monetary Policy in the United States

Because the genesis of the financial crisis was in the United States and other advanced economies, the much weaker recovery in those economies compared with that in the emerging markets may not be entirely unexpected (although, given their traditional vulnerability to crises, the resilience of the emerging market economies over the past few years is both notable and encouraging). What is clear is that the different cyclical positions of the advanced and emerging market economies call for different policy settings. Although the details of the outlook vary among jurisdictions, most advanced economies still need accommodative policies to continue to lay the groundwork for a strong, durable recovery. Insufficiently supportive policies in the advanced economies could undermine the recovery not only in those economies, but for the world as a whole. In contrast, emerging market economies increasingly face the challenge of maintaining robust growth while avoiding overheating, which may in some cases involve the measured withdrawal of policy stimulus.

Let me address the case of the United States specifically. As I described, the U.S. unemployment rate is high and, given the slow pace of economic growth, likely to remain so for some time. Indeed, although I expect that growth will pick up and unemployment will decline somewhat next year, we cannot rule out the possibility that unemployment might rise further in the near term, creating added risks for the recovery. Inflation has declined noticeably since the business cycle peak, and further disinflation could hinder the recovery. In particular, with shorter-term nominal interest rates close to zero, declines in actual and expected inflation imply both higher realized and expected real interest rates, creating further drags on growth.2 In light of the significant risks to the economic recovery, to the health of the labor market, and to price stability, the FOMC decided that additional policy support was warranted.

Again, fear of deflation, especially via expectations theory.

The Federal Reserve’s policy target for the federal funds rate has been near zero since December 2008,

And not done the trick. And no mention that the interest income channels might be the culprits.

so another means of providing monetary accommodation has been necessary since that time. Accordingly, the FOMC purchased Treasury and agency-backed securities on a large scale from December 2008 through March 2010,

Further reducing interest income earned by the private sector.

a policy that appears to have been quite successful in helping to stabilize the economy and support the recovery during that period.

I attribute the stabilization to the automatic fiscal stabilizers increasing federal deficit spending, adding that much income and savings to the economy.

Following up on this earlier success, the Committee announced this month that it would purchase additional Treasury securities. In taking that action, the Committee seeks to support the economic recovery, promote a faster pace of job creation, and reduce the risk of a further decline in inflation that would prove damaging to the recovery.

Although securities purchases are a different tool for conducting monetary policy than the more familiar approach of managing the overnight interest rate, the goals and transmission mechanisms are very similar. In particular, securities purchases by the central bank affect the economy primarily by lowering interest rates on securities of longer maturities,

Very good! Looks like the officials in monetary operations have finally gotten the point across. It’s been no small effort.

just as conventional monetary policy, by affecting the expected path of short-term rates, also influences longer-term rates. Lower longer-term rates in turn lead to more accommodative financial conditions, which support household and business spending. As I noted, the evidence suggests that asset purchases can be an effective tool; indeed, financial conditions eased notably in anticipation of the Federal Reserve’s policy announcement.

Incidentally, in my view, the use of the term “quantitative easing” to refer to the Federal Reserve’s policies is inappropriate. Quantitative easing typically refers to policies that seek to have effects by changing the quantity of bank reserves, a channel which seems relatively weak, at least in the U.S. context.

While the channel is more than weak- it doesn’t even exist- even here his story has improved.

In contrast, securities purchases work by affecting the yields on the acquired securities and, via substitution effects in investors’ portfolios, on a wider range of assets.

Leaving out that they remove interest income from the private sector.

This policy tool will be used in a manner that is measured and responsive to economic conditions. In particular, the Committee stated that it would review its asset-purchase program regularly in light of incoming information and would adjust the program as needed to meet its objectives. Importantly, the Committee remains unwaveringly committed to price stability and does not seek inflation above the level of 2 percent or a bit less that most FOMC participants see as consistent with the Federal Reserve’s mandate. In that regard, it bears emphasizing that the Federal Reserve has worked hard to ensure that it will not have any problems exiting from this program at the appropriate time. The Fed’s power to pay interest on banks’ reserves held at the Federal Reserve will allow it to manage short-term interest rates effectively and thus to tighten policy when needed, even if bank reserves remain high. Moreover, the Fed has invested considerable effort in developing tools that will allow it to drain or immobilize bank reserves as needed to facilitate the smooth withdrawal of policy accommodation when conditions warrant. If necessary, the Committee could also tighten policy by redeeming or selling securities.

Not bad!

The foreign exchange value of the dollar has fluctuated considerably during the course of the crisis, driven by a range of factors. A significant portion of these fluctuations has reflected changes in investor risk aversion, with the dollar tending to appreciate when risk aversion is high. In particular, much of the decline over the summer in the foreign exchange value of the dollar reflected an unwinding of the increase in the dollar’s value in the spring associated with the European sovereign debt crisis.

Agreed.

The dollar’s role as a safe haven during periods of market stress stems in no small part from the underlying strength and stability that the U.S. economy has exhibited over the years.

Further supported by the desire of foreign govts to support exports to the US, but that is a different matter.

Fully aware of the important role that the dollar plays in the international monetary and financial system, the Committee believes that the best way to continue to deliver the strong economic fundamentals that underpin the value of the dollar, as well as to support the global recovery, is through policies that lead to a resumption of robust growth in a context of price stability in the United States.

This is a bit defensive, as it implies he does believe QE itself weakens the dollar in the near term. If he knew that wasn’t the case he would have stated it all differently.

In sum, on its current economic trajectory the United States runs the risk of seeing millions of workers unemployed or underemployed for many years. As a society, we should find that outcome unacceptable. Monetary policy is working in support of both economic recovery and price stability, but there are limits to what can be achieved by the central bank alone. The Federal Reserve is nonpartisan and does not make recommendations regarding specific tax and spending programs. However, in general terms, a fiscal program that combines near-term measures to enhance growth with strong, confidence-inducing steps to reduce longer-term structural deficits would be an important complement to the policies of the Federal Reserve.

Ok, it’s something.

But how about repeating that operationally, govt spending is not constrained by revenues, and therefore there is no solvency problem? That’s not politics, just monetary operations.

He could also explain how tsy secs are functionally nothing more than time deposits at the Fed, while reserves are overnight deposits, and funding the deficit and paying it down are nothing more than shifting dollar balances from reserve accounts to securities accounts, and from securities accounts to reserve accounts.

And he could spell out the accounting identity that govt deficits add exactly that much to net financial assets of the non govt sectors.

In other words, he could easily dispel the deficit myths that are preventing the policy he is recommending.

So why not???

Global Policy Challenges and Tensions

The two-speed nature of the global recovery implies that different policy stances are appropriate for different groups of countries. As I have noted, advanced economies generally need accommodative policies to sustain economic growth. In the emerging market economies, by contrast, strong growth and incipient concerns about inflation have led to somewhat tighter policies.

Unfortunately, the differences in the cyclical positions and policy stances of the advanced and emerging market economies have intensified the challenges for policymakers around the globe. Notably, in recent months, some officials in emerging market economies and elsewhere have argued that accommodative monetary policies in the advanced economies, especially the United States, have been producing negative spillover effects on their economies. In particular, they are concerned that advanced economy policies are inducing excessive capital inflows to the emerging market economies, inflows that in turn put unwelcome upward pressure on emerging market currencies and threaten to create asset price bubbles. As is evident in figure 6, net private capital flows to a selection of emerging market economies (based on national balance of payments data) have rebounded from the large outflows experienced during the worst of the crisis. Overall, by this broad measure, such inflows through the second quarter of this year were not any larger than in the year before the crisis, but they were nonetheless substantial. A narrower but timelier measure of demand for emerging market assets–net inflows to equity and bond funds investing in emerging markets, shown in figure 7–suggests that inflows of capital to emerging market economies have indeed picked up in recent months.

To a large degree, these capital flows have been driven by perceived return differentials that favor emerging markets, resulting from factors such as stronger expected growth–both in the short term and in the longer run–and higher interest rates, which reflect differences in policy settings as well as other forces. As figures 6 and 7 show, even before the crisis, fast-growing emerging market economies were attractive destinations for cross-border investment. However, beyond these fundamental factors, an important driver of the rapid capital inflows to some emerging markets is incomplete adjustment of exchange rates in those economies, which leads investors to anticipate additional returns arising from expected exchange rate appreciation.

The exchange rate adjustment is incomplete, in part, because the authorities in some emerging market economies have intervened in foreign exchange markets to prevent or slow the appreciation of their currencies. The degree of intervention is illustrated for selected emerging market economies in figure 8. The vertical axis of this graph shows the percent change in the real effective exchange rate in the 12 months through September. The horizontal axis shows the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves as a share of GDP over the same period. The relationship evident in the graph suggests that the economies that have most heavily intervened in foreign exchange markets have succeeded in limiting the appreciation of their currencies. The graph also illustrates that some emerging market economies have intervened at very high levels and others relatively little. Judging from the changes in the real effective exchange rate, the emerging market economies that have largely let market forces determine their exchange rates have seen their competitiveness reduced relative to those emerging market economies that have intervened more aggressively.

It is striking that, amid all the concerns about renewed private capital inflows to the emerging market economies, total capital, on net, is still flowing from relatively labor-abundant emerging market economies to capital-abundant advanced economies. In particular, the current account deficit of the United States implies that it experienced net capital inflows exceeding 3 percent of GDP in the first half of this year. A key driver of this “uphill” flow of capital is official reserve accumulation in the emerging market economies that exceeds private capital inflows to these economies. The total holdings of foreign exchange reserves by selected major emerging market economies, shown in figure 9, have risen sharply since the crisis and now surpass $5 trillion–about six times their level a decade ago. China holds about half of the total reserves of these selected economies, slightly more than $2.6 trillion.

It is instructive to contrast this situation with what would happen in an international system in which exchange rates were allowed to fully reflect market fundamentals. In the current context, advanced economies would pursue accommodative monetary policies as needed to foster recovery and to guard against unwanted disinflation. At the same time, emerging market economies would tighten their own monetary policies to the degree needed to prevent overheating and inflation. The resulting increase in emerging market interest rates relative to those in the advanced economies would naturally lead to increased capital flows from advanced to emerging economies and, consequently, to currency appreciation in emerging market economies. This currency appreciation would in turn tend to reduce net exports and current account surpluses in the emerging markets, thus helping cool these rapidly growing economies while adding to demand in the advanced economies. Moreover, currency appreciation would help shift a greater proportion of domestic output toward satisfying domestic needs in emerging markets. The net result would be more balanced and sustainable global economic growth.

Given these advantages of a system of market-determined exchange rates, why have officials in many emerging markets leaned against appreciation of their currencies toward levels more consistent with market fundamentals? The principal answer is that currency undervaluation on the part of some countries has been part of a long-term export-led strategy for growth and development. This strategy, which allows a country’s producers to operate at a greater scale and to produce a more diverse set of products than domestic demand alone might sustain, has been viewed as promoting economic growth and, more broadly, as making an important contribution to the development of a number of countries. However, increasingly over time, the strategy of currency undervaluation has demonstrated important drawbacks, both for the world system and for the countries using that strategy.

First, as I have described, currency undervaluation inhibits necessary macroeconomic adjustments and creates challenges for policymakers in both advanced and emerging market economies. Globally, both growth and trade are unbalanced, as reflected in the two-speed recovery and in persistent current account surpluses and deficits. Neither situation is sustainable. Because a strong expansion in the emerging market economies will ultimately depend on a recovery in the more advanced economies, this pattern of two-speed growth might very well be resolved in favor of slow growth for everyone if the recovery in the advanced economies falls short. Likewise, large and persistent imbalances in current accounts represent a growing financial and economic risk.

Second, the current system leads to uneven burdens of adjustment among countries, with those countries that allow substantial flexibility in their exchange rates bearing the greatest burden (for example, in having to make potentially large and rapid adjustments in the scale of export-oriented industries) and those that resist appreciation bearing the least.

Third, countries that maintain undervalued currencies may themselves face important costs at the national level, including a reduced ability to use independent monetary policies to stabilize their economies and the risks associated with excessive or volatile capital inflows. The latter can be managed to some extent with a variety of tools, including various forms of capital controls, but such approaches can be difficult to implement or lead to microeconomic distortions. The high levels of reserves associated with currency undervaluation may also imply significant fiscal costs if the liabilities issued to sterilize reserves bear interest rates that exceed those on the reserve assets themselves. Perhaps most important, the ultimate purpose of economic growth is to deliver higher living standards at home; thus, eventually, the benefits of shifting productive resources to satisfying domestic needs must outweigh the development benefits of continued reliance on export-led growth.

Improving the International System

The current international monetary system is not working as well as it should. Currency undervaluation by surplus countries is inhibiting needed international adjustment and creating spillover effects that would not exist if exchange rates better reflected market fundamentals. In addition, differences in the degree of currency flexibility impose unequal burdens of adjustment, penalizing countries with relatively flexible exchange rates. What should be done?

The answers differ depending on whether one is talking about the long term or the short term. In the longer term, significantly greater flexibility in exchange rates to reflect market forces would be desirable and achievable. That flexibility would help facilitate global rebalancing and reduce the problems of policy spillovers that emerging market economies are confronting today. The further liberalization of exchange rate and capital account regimes would be most effective if it were accompanied by complementary financial and structural policies to help achieve better global balance in trade and capital flows. For example, surplus countries could speed adjustment with policies that boost domestic spending, such as strengthening the social safety net, improving retail credit markets to encourage domestic consumption, or other structural reforms. For their part, deficit countries need to do more over time to narrow the gap between investment and national saving. In the United States, putting fiscal policy on a sustainable path is a critical step toward increasing national saving in the longer term. Higher private saving would also help. And resources will need to shift into the production of export- and import-competing goods. Some of these shifts in spending and production are already occurring; for example, China is taking steps to boost domestic demand and the U.S. personal saving rate has risen sharply since 2007.

In the near term, a shift of the international regime toward one in which exchange rates respond flexibly to market forces is, unfortunately, probably not practical for all economies. Some emerging market economies do not have the infrastructure to support a fully convertible, internationally traded currency and to allow unrestricted capital flows. Moreover, the internal rebalancing associated with exchange rate appreciation–that is, the shifting of resources and productive capacity from production for external markets to production for the domestic market–takes time.

That said, in the short term, rebalancing economic growth between the advanced and emerging market economies should remain a common objective, as a two-speed global recovery may not be sustainable. Appropriately accommodative policies in the advanced economies help rather hinder this process. But the rebalancing of growth would also be facilitated if fast-growing countries, especially those with large current account surpluses, would take action to reduce their surpluses, while slow-growing countries, especially those with large current account deficits, take parallel actions to reduce those deficits. Some shift of demand from surplus to deficit countries, which could be compensated for if necessary by actions to strengthen domestic demand in the surplus countries, would accomplish two objectives. First, it would be a down payment toward global rebalancing of trade and current accounts, an essential outcome for long-run economic and financial stability. Second, improving the trade balances of slow-growing countries would help them grow more quickly, perhaps reducing the need for accommodative policies in those countries while enhancing the sustainability of the global recovery. Unfortunately, so long as exchange rate adjustment is incomplete and global growth prospects are markedly uneven, the problem of excessively strong capital inflows to emerging markets may persist.

Conclusion

As currently constituted, the international monetary system has a structural flaw: It lacks a mechanism, market based or otherwise, to induce needed adjustments by surplus countries, which can result in persistent imbalances. This problem is not new. For example, in the somewhat different context of the gold standard in the period prior to the Great Depression, the United States and France ran large current account surpluses, accompanied by large inflows of gold. However, in defiance of the so-called rules of the game of the international gold standard, neither country allowed the higher gold reserves to feed through to their domestic money supplies and price levels, with the result that the real exchange rate in each country remained persistently undervalued. These policies created deflationary pressures in deficit countries that were losing gold, which helped bring on the Great Depression.3 The gold standard was meant to ensure economic and financial stability, but failures of international coordination undermined these very goals. Although the parallels are certainly far from perfect, and I am certainly not predicting a new Depression, some of the lessons from that grim period are applicable today.4 In particular, for large, systemically important countries with persistent current account surpluses, the pursuit of export-led growth cannot ultimately succeed if the implications of that strategy for global growth and stability are not taken into account.

Thus, it would be desirable for the global community, over time, to devise an international monetary system that more consistently aligns the interests of individual countries with the interests of the global economy as a whole. In particular, such a system would provide more effective checks on the tendency for countries to run large and persistent external imbalances, whether surpluses or deficits. Changes to accomplish these goals will take considerable time, effort, and coordination to implement. In the meantime, without such a system in place, the countries of the world must recognize their collective responsibility for bringing about the rebalancing required to preserve global economic stability and prosperity. I hope that policymakers in all countries can work together cooperatively to achieve a stronger, more sustainable, and more balanced global economy.