Not a quick read, but telling – inflation risks seem to be overtaking concerns with the economy:

Does Stabilizing Inflation Contribute to Stabilizing Economic Activity?

(Interesting that this is a question)

The ultimate purpose of a central bank should be to promote the public good through policies that foster economic prosperity. Research in monetary economics describes this purpose by specifying monetary policy objectives in terms of stabilizing both inflation and economic activity. Indeed, this specification of monetary policy objectives is exactly what is suggested by the dual mandate that the Congress has given to the Federal Reserve to promote both price stability and maximum employment.1

Yes, just as the mainstream says, and FOMC voting member Fisher restate recently: price stability is a necessary condition for optimal long-term employment and growth.

We might worry that, under some circumstances, the objectives of stabilizing inflation and economic activity could conflict, particularly in the short run. However, economic research over the past three decades suggests that such conflicts may not, in fact, be that serious. Indeed, stabilizing inflation and stabilizing economic activity are mutually reinforcing not only in the long run, but in the short run as well. In my remarks today, I would like to outline how economic researchers came to that conclusion, and in so doing, explain why it is so important to achieve and maintain price stability.2

Seems the emphasis is now on price stability. The question remains whether talk will translate to action.

The Long Run

Both economic theory and empirical evidence indicate that the stabilization of inflation promotes stronger economic activity in the long run.3

(I don’t agree, but that’s another story. Congressmen do, however, need low inflation to stay in office, hence the dual mandate.)

Two principles underlie that conclusion. The first principle is that low inflation is beneficial for economic welfare. Rates of inflation significantly above the low levels of recent years can have serious adverse effects on economic efficiency and hence on output in the long run. The distortions from a moderate to high level of long-run inflation are many. High inflation can cause confusion among households and firms, thereby distorting savings and investment decisions (Lucas, 1972; Briault, 1995; Shafir, Diamond, and Tversky, 1997).

(I don’t agree that these ‘distortions’, if any, are qualitatively less supportive of public purpose.)

The interaction of inflation and the tax code, which is often applied to nominal income, can have adverse effects, especially on the incentive of firms to invest in productive capital (Feldstein, 1997).

(If so, that’s a reason to adjust the tax code, rather than a ‘problem’ with inflation per se?)

Infrequent nominal price adjustment implies that high inflation results in distorted relative prices, thereby leading to an inefficient allocation of resources (Woodford, 2003).

(Versus our current allocation of real resources??? But yes, these are the mainstream pillars.)

And high inflation distorts the financial sector as firms and households demand greater protection from inflation’s erosion of the value of cash holdings (English, 1999).

As above. It’s already hard to pin down any real value added to most, if not all our financial sector…

The second principle is the lack of a long-run tradeoff between unemployment and the inflation rate. Rather, the long-run Phillips curve is vertical, implying that the economy gravitates to some natural rate of unemployment in the long run no matter what the rate of inflation is (Friedman, 1968; Phelps, 1968).4

And the mainstream also adds ‘no matter what the fiscal balance’.

The natural rate, in turn, is determined by the structure of labor and product markets, including elements such as the ease with which people who lose their jobs can find new employment and the pace at which technological progress creates new industries and occupations while shrinking or eliminating others. Importantly, those structural features of the economy are outside the control of monetary policy. As a result, any attempt by a central bank to keep unemployment below the natural rate would prove fruitless. Such a strategy would only lead to higher inflation that, as the first principle suggests, would lower economic activity and household welfare in the long run.

Yes, the mainstream believes this, and the general assumption is that 4.75% is currently the natural rate of unemployment. January unemployment was reported at 4.9%; so, this implies we are already very near full employment, and therefore lowering rates to help the economy may only generate more inflation, and not more output.

Empirical evidence has starkly demonstrated the adverse effects of high inflation (e.g., see the surveys in Fischer, 1993, and Anderson and Gruen, 1995). In most industrialized countries, the late 1960s to early 1980s was a period during which inflation rose to high levels while economic activity stagnated. While many factors contributed to the improved economic performance of recent decades, policymakers’ focus on low and stable inflation was likely an important factor.5

Correct, only ‘likely’. I attribute other factors to the real performance, but, again, that’s another story.

The Short Run

Although there is no long-run tradeoff between unemployment and inflation, in the short run, expansionary monetary policy that raises inflation can lower unemployment and raise employment. That is, the short-run Phillips curve is not vertical.

(This is also theoretically and empirically subject to much recent debate.)

That fact would seem to suggest that achieving the dual goals of price stability and maximum sustainable employment might at times conflict. However, several lines of research provide support for the view that stabilization of inflation and economic activity can be complementary rather than in conflict.

Economists have long recognized that some sources of economic fluctuations imply that output stability and inflation stability are mutually reinforcing. Consider a negative shock to aggregate demand (such as a decline in consumer confidence) that causes households to cut spending. The drop in demand leads, in turn, to a decline in actual output relative to its potential–that is, the level of output that the economy can produce at the maximum sustainable level of employment. As a result of increased slack in the economy, future inflation will fall below levels consistent with price stability, and the central bank will pursue an expansionary policy to keep inflation from falling.

Yes, the FOMC has believed increased slack would bring down the level of inflation. And, they further believed that there was some risk of a total financial collapse, which would result in a massive 1930s style deflation. Not sure if they still do.

The expansionary policy will then result in an increase in demand that boosts output toward its potential to return inflation to a level consistent with price stability. Stabilizing output thus stabilizes inflation and vice versa under these conditions.

For example, the Federal Reserve reduced its target for the federal funds rate a total of 5-1/2 percentage points during the 2001 recession; that stimulus not only contributed to economic recovery but also helped to avoid an unwelcome decline in inflation below its already low level.

The international context was deflationary, as import prices were falling and putting downward pressure on domestic prices. (Also, the Fed economists trace the recovery to the ‘fiscal impulses’ rather than the lower interest rates.)

At other times, a tightening of the stance of monetary policy has prevented the economy from overheating and generating a boom-bust cycle in the level of employment as well as an undesirable upward spurt of inflation.

This is also difficult to separate from the fiscal cycle, but, again, it is the mainstream view.

One critical precondition for effective central-bank easing in response to adverse demand shocks is anchored long-run inflation expectations. Otherwise, lowering short-term interest rates could raise inflation expectations, which might lead to higher, rather than lower, long-term interest rates, thereby depriving monetary policy of one of its key transmission channels for stimulating the economy.

Yes, the mainstream considers inflation expectations as the critical determinant of the price level.

The role of expectations illustrates two additional basic principles of monetary policy that help explain why stabilizing inflation helps stabilize economic activity: First, expectations of future policy actions and accompanying economic conditions play a crucial role in determining the effects of current policy actions on the economy. Second, monetary policy is most effective when the central bank is firmly committed, through its actions and statements, to a “nominal anchor”–such as to keeping inflation low and stable. A strong commitment to stabilizing inflation helps anchor inflation expectations so that a central bank will not have to worry that expansionary policy to counter a negative demand shock will lead to a sharp rise in expected inflation–a so-called inflation scare (Goodfriend, 1993, 2005). Such a scare would not only blunt the effects of lower short-term interest rates on real activity but would also push up actual inflation in the future. Thus, a strong commitment to a nominal anchor enables a central bank to react more aggressively to negative demand shocks and, therefore, to prevent rapid declines in employment or output.

The last few weeks have seen an elevated use of this kind of definitive, hawkish language, even from some of the Fed doves.

Unlike demand shocks, which drive inflation and economic activity in the same direction and thus present policymakers with a clear signal for how to adjust policy, supply shocks, such as the increases in the price of energy that we have been experiencing lately, drive inflation and output in opposite directions. In this case, because tightening monetary policy to reduce inflation can lead to lower output, the goal of stabilizing inflation might conflict with the goal of stabilizing economic activity.

Yes, that is what they see developing as the current set of options.

Here again, a strong, previously established commitment to stabilizing inflation can help stabilize economic activity, because supply shocks, such as a rise in relative energy prices, are likely to have only a temporary effect on inflation in such circumstances. When inflation expectations are well anchored, the central bank does not necessarily need to raise interest rates aggressively to keep inflation under control following an aggregate supply shock. Hence, the commitment to price stability can help avoid imposing unnecessary hardship on workers and the economy more broadly.

The Fed has to manage expectations at all times.

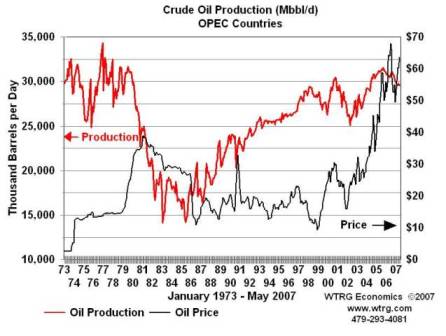

The experience of recent decades supports the view that a substantial conflict between stabilizing inflation and stabilizing output in response to supply shocks does not arise if inflation expectations are well anchored. The oil shocks in the 1970s caused large increases in inflation not only through their direct effects on household energy prices but also through their “second round” effects on the prices of other goods that reflected, in part, expectations of higher future inflation.

Yes, that’s the mainstream theory.

Sharp economic downturns followed, driven partly by restrictive monetary policy actions taken in response to the inflation outbreaks. In contrast, the run-up in energy prices since 2003 has had only modest effects on inflation for other goods;

(Seems to me it took about three years this time, about the same as back then?)

as a result, monetary policy has been able to avoid responding precipitously to higher oil prices. More generally, the period from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s was one of relatively high and volatile inflation; at the same time, real activity was very volatile. Since the early 1980s, central banks have put greater weight on achieving low and stable inflation, while during the same period, real activity stabilized appreciably.

(Energy and commodity prices also fell with excess supply and then stabilized for almost two decades, bringing down and stabilizing core inflation and stabilizing real activity.)

Many factors were likely at work, but this experience suggests that inflation stabilization does not have to come at the cost of greater volatility of real activity; in fact, it suggests that, by anchoring inflation expectations, low and stable inflation is an important precondition for macroeconomic stability.

Research over the past decade using so-called New Keynesian models has added further support to the proposition that inflation stabilization may contribute to stabilizing employment and output at their maximum sustainable levels. This research has also led to a deeper understanding of the benefits of price stability and the setting of monetary policy in response to changes in economic activity and inflation.

Repeating the need for price stability as a necessary condition for optimal employment and growth.

In particular, research has emphasized the interaction between stabilizing inflation and economic activity and has found that price stability can contribute to overall economic stability in a range of circumstances. The intuition

Okay.

that leads to the conclusion that stabilizing inflation promotes maximum sustainable output and employment is simple, and it holds in a range of economic models whose policy prescriptions have been dubbed the New Neoclassical Synthesis. To begin, the prices of many goods and services adjust infrequently. Accordingly, under general price inflation, the prices of some goods and services are changing while other prices do not, thus distorting relative prices between different goods and services. As a consequence, the profitability of producing the various goods and services no longer reflects the relative social costs of producing them, which in turn yields an inefficient allocation of resources.

(Only if there was efficiency in the first place, where many if not most prices are ‘cost plus’ and institutional structure determines many others, such as health care prices, tax laws, corporate law, etc.)

A policy of price stability minimizes those inefficiencies (Goodfriend and King, 1997; Rotemberg and Woodford, 1997; Woodford, 2003).

There are several subtleties here. First, in some circumstance, relative prices should change. For example, the rapid technological advances in the production of information-technology goods witnessed over the past decades mean that the prices of these goods relative to other goods and services should decline, because fewer economic resources are required for their production. Conversely, shifts in the balance between global demand for, and supply of, oil require that relative prices change to achieve an appropriate reallocation of resources–in this case, the reduced use of expensive energy.

(Makes me wonder how does a financial package designed to help people pay their energy and food bills fits in?)

Thus, the policy prescription refers to stability of the price level as a whole, not to the stability of each individual price.

Second, the New Neoclassical Synthesis suggests that only those prices that move sluggishly, referred to as sticky prices, should be stabilized. Indeed, these models indicate that monetary policy should try to get the economy to operate at the same level that would prevail if all prices were flexible–that is, at the so-called natural rate of output or employment. Stabilizing sticky prices helps the economy get close to the theoretical flexible-price equilibrium because it keeps sticky prices from moving away from their appropriate relative level while flexible prices are adjusting to their own appropriate relative level. The New Neoclassical Synthesis, therefore, does not suggest that headline inflation, in which the weight on flexible prices is larger, should be stabilized. For example, to the extent that households directly consume energy goods with flexible prices, such as gasoline, headline inflation should be allowed to increase in response to an oil price shock. At the same time, insofar as energy enters as an input in the production of goods whose prices are sticky, stabilizing the level of sticky prices would require that the increase in energy-intensive goods prices be offset by declines in the prices of other goods.

Yes – AKA, ‘Don’t let a relative value story turn into an inflation story.’

That reasoning suggests that monetary policy should focus on stabilizing a measure of “core” inflation, which is made up mostly of sticky prices. Simulations with FRB/US, the model of the U.S. economy created and maintained by the staff of the Federal Reserve Board (Mishkin, 2007b), illustrate this point. To keep the simulations as simple as possible, I have assumed that the economy begins at full employment with both headline and core inflation at desired levels. The economy is then assumed to experience a shock that raises the world price of oil about $30 per barrel over two years;

(It actually went up more than that.)

the shock is assumed to slowly dissipate thereafter.

(It hasn’t yet, hence the problem of core converging to headline when headline trends.)

In each of two scenarios, a Taylor rule is assumed to govern the response of the federal funds rate; the only difference between the two scenarios is that in one, the federal funds rate responds to core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation, whereas in the other, it responds to headline PCE inflation.6 Figure 1 illustrates the results of those two scenarios. The federal funds rate jumps higher and faster when the central bank responds to headline inflation rather than to core inflation, as would be expected (top-left panel). Likewise, responding to headline inflation pushes the unemployment rate markedly higher than otherwise in the early going (top-right panel),

Maybe. This function has not held true in recent history.

and produces an inflation rate that is slightly lower than otherwise,

As above.

whether measured by core or headline indexes (bottom panels). More important, even for a shock as persistent as this one, the policy response under headline inflation has to be unwound in the sense that the federal funds rate must drop substantially below baseline once the first-round effects of the shock drop out of the inflation data.7

The basic point from these simulations is that monetary policy that responds to headline inflation rather than to core inflation in response to an oil price shock pushes unemployment markedly higher than monetary policy that responds to core inflation. In addition, because this policy has larger swings in the federal funds rate that must be reversed, it leads to more pronounced swings in unemployment. On the other hand, monetary policy that responds to core inflation does not lead to appreciably worse performance on stabilizing inflation than does monetary policy that responds to headline inflation. Stabilizing core inflation, therefore, leads to better economic outcomes than stabilizing headline inflation.

Yes, they firmly believe that.

Although the simplest sticky-price models imply that stabilizing sticky-price inflation and economic activity are two sides of the same coin, the presence of other frictions besides sticky prices can lead to instances in which completely stabilizing sticky-price inflation would not imply stabilizing employment (or output) around their natural rates. For example, in response to an increase in productivity (a positive technology shock), the real wage has to rise to reflect the higher marginal product of labor inputs, which requires either prices to fall or nominal wages to rise for employment to reach its natural rate. If both nominal wages and prices are sticky, a policy of completely stabilizing prices will force the necessary real wage adjustment to occur entirely through nominal wage adjustment, thereby impeding the adjustment of employment to its efficient level (Blanchard, 1997; Erceg, Henderson, and Levin, 2000). Indeed, if wages are much stickier than prices, the best strategy is to stabilize nominal wage inflation rather than price inflation, thereby allowing price inflation to decline to achieve the required increase in real wages.

Makes sense under mainstream assumptions.

Fluctuations in inflation and economic activity induced by variation over time in sources of economic inefficiency, such as changes in the markups in goods and labor markets or inefficiencies in labor market search, could also drive a wedge between the goals of stabilizing inflation and economic activity (Blanchard and GalÃÂÂ, 2006; GalÃÂÂ, Gertler, and López-Salido, 2007). For example, in sectors of the economy subject to little competitive pressure, prices that firms set tend to be higher and output lower than would prevail under greater competition. Monetary policy is, of course, unable to offset permanently high markups because of the principle, mentioned earlier, that the long-run Phillips curve is vertical. However, a temporary increase in monopoly power that raises markups would exert upward pressure on prices without, at the same time, reducing the productive potential of the economy. That would, indeed, be a case of a tradeoff between stabilizing inflation and stabilizing output.

How about a non-resident monopolist at the margin, like the Saudis?

These examples narrow the degree to which the recent findings of congruence between stabilizing inflation and economic activity apply in all cases, but they do not necessarily overturn the findings. The example of sticky wages would not invalidate the view that stabilizing inflation stabilizes economic activity if wages are sticky, for example, because they are held constant in order to operate as an “insurance” contract between employers and workers (Goodfriend and King, 2001). And for many of the inefficient shocks that drive a wedge between the sustainable level of output and the level of output associated with price stability, monetary policy may be the wrong tool to offset their effects (Blanchard, 2005).

Of course, central banks at times will still face difficult decisions regarding the short-run tradeoff between stabilizing inflation and output. For example, judging from the fit of New Keynesian Phillips curves, a substantial fraction of overall inflation variability seems related to supply-type shocks

(Rather than a ‘monetary phenomena’ as they say, inflation can be a supply shock phenomena?)

that create a tradeoff between inflation and output-gap stabilization (Kiley, 2007b). But the key insight from recent research–that the interaction between inflation fluctuations and relative price distortions should lead to a focus on the stability of nominal prices that adjust sluggishly–will likely prove to have important practical implications that can help contribute to inflation and employment stabilization.

Stabilizing Inflation as a Robust Policy in the Presence of Uncertainty

The discussion so far has been based on the premise that the central bank knows the efficient, or natural, rate of output or employment. However, the natural rates of employment and output cannot be directly observed and are subject to considerable uncertainty–particularly in real time. Indeed, economists do not even agree on the economic theory or econometric methods that should be used to measure those rates.

(And I can give you some good reasons there is no natural rate of unemployment as well.)

These concerns are perhaps even more severe in the most recent models, where fluctuations in natural rates of output or employment can be very substantial (for example, Rotemberg and Woodford, 1997; Edge, Kiley, and Laforte, forthcoming). Furthermore, because the natural rates in the most recent models are defined as the counterfactual levels of output and employment that would be obtained if prices and wages were completely flexible, the estimated fluctuations in natural rates generated by the research are very sensitive to model specification.

If a central bank errs in measuring the natural rates of output and employment, its attempts to stabilize economic activity at those mismeasured natural rates can lead to very poor outcomes. For example, most economists now agree that the natural unemployment rate shifted up for many years starting in the late 1960s and that the growth of potential output shifted down for a considerable time after 1970. However, perhaps because those shifts were not generally recognized until much later (Orphanides and van Norden, 2002; Orphanides, 2003), monetary policy in the 1970s seems to have been aimed at achieving unsustainable levels of output and employment. Hence, policymakers may have unwittingly contributed to accelerating inflation that reached double digits by the end of the decade as well as undesirable swings in unemployment. And although subsequent monetary policy tightening was successful in regaining control of inflation, the toll was a severe recession in 1981-82, which pushed up the unemployment rate to around 10 percent.

How about the tight fiscal policy from the interaction of inflation and the tax structure (described by Governor Mishkin above) that drove the budget to a small surplus in 1979, along with oil gapping from $20 to $40 as the Saudis hiked price and accumulated $US financial assets rather than spending their income, which drained aggregate demand from the US economy.

Uncertainty about the natural rates of economic activity implies that less weight may need to be put on stabilizing output or employment around what is likely to be a mismeasured natural rate (Orphanides and Williams, 2002). Furthermore, research with New Keynesian models has found that overall economic performance may be most efficiently achieved by policies with a heavy focus on stabilizing inflation (for example, Schmitt-Grohé and Uribe, 2007).

Back to stabilizing inflation, the main theme of the speech.

Conclusion

Because monetary policy has not one but two objectives, stabilizing inflation and stabilizing economic activity, it might seem obvious that those objectives would usually, if not always, conflict. As so often occurs with the “obvious,” however, the impression turns out to be incorrect. The economic research that I have discussed today demonstrates, rather, that the objectives of price stability and stabilizing economic activity are often likely to be mutually reinforcing. Thus, the answer to the title of this speech–“Does stabilizing inflation contribute to stabilizing economic activity?”–is, for the most part, yes.

Price stability is a necessary condition for optimal employment and growth.

A key policy recommendation from the past three decades of research in monetary economics is that monetary policy makers must always keep their eye on inflation and emphasize the importance of price stability in their actions and communications.

First time I’ve seen the word ‘action’ regarding inflation, and it’s placed first.

Doing so does not mean that monetary policy makers are less concerned about stabilizing economic activity. Rather, by appropriately focusing on stabilizing inflation along the lines I have outlined here, monetary policy is more likely to better stabilize economic activity.

A speech can’t get any more hawkish than that.

Lots of data between now and March 18th.

I still expect weakness and rising inflation.