So it was buy the rumor, buy the news, then watch it all fall apart a few days later.

QE was a major international event, with the word being that the ‘money printing’ would not only take down the dollar, but also spread ‘liquidity’ to the rest of the world through the US banking system, via some kind of ‘carry trades’ and who knows what else, or needed to know. It was just obvious…

So the entire world was front running QE in every currency, commodity, and equity market.

And the Fed announcement only brought in more international players, with money printing headlines screaming globally.

Then the ‘risk off’ unwinding phase started, reversing what had been driven by maybe three themes:

1. There were those who knew all along QE probably did not do anything of consequence, but went along for the ‘risk on’ ride believing others believed QE worked and would drive prices accordingly.

2. A group that thought originally QE might do something and piled in, but began having second thoughts about how effective QE might actually be after learning more about it, and decided to get out.

3. A third group who continue to believe QE does work, who got cold feed when they started doubting whether the Fed would actually follow through with enough QE, also for two reasons.

a. the FOMC itself made it clear opinion was highly polarized, often for contradictory reasons

b. the economy showed signs of modest growth that cast doubts on whether the Fed might

think something as ‘powerful and risky’ as QE was still needed.

Reminds me some of the old quip- the food was terrible and the portions were small-

(QE is questionable policy and they aren’t going to do enough of it.)

So risk off continues in what have become fundamentally illiquid markets until some time after the speculative longs have been sold and the shorts covered.

Next question, what about after the smoke clears?

A. The dollar could remain strong even after the initial short covering ends- the modest GDP growth is slowly tightening fiscal, and crude oil prices are falling, both of which make dollars ‘harder to get’

It’s starting a kind of virtuous cycle where the stronger dollar moves crude lower which strengthens the dollar.

Also, the J curve works in reverse with other imports as well. As imports get cheaper, initially

the rest of world gets fewer dollars from exports to the US, until/unless volumes pick up.

The euro zone is again struggling with the idea of the ECB supporting the weaker members with secondary market bond purchases, as ECB imposed austerity measures are showing signs of decreasing revenues of the more troubled members. Seems taxpayers of the core members are resisting allowing the ECB to support the weaker members, and the core leaders are groping for something that works politically and financially. All this adds risk to holding euro financial assets, as even a small threat of a breakup jeopardizes the very existence of the euro.

Japan is on the way to fiscal easing while the US, UK, and euro zone are attempting to tighten fiscal.

Falling commodity prices hurt the commodity currencies.

B. Interest rates are moving higher as spec longs who bought the QE rumor and news are getting out.

But it looks to me like term rates could again move back down after this sell off has run its course.

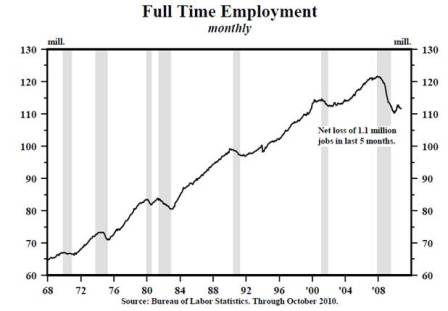

The Fed still failing on both mandates- real growth is still modest at best, and the 0 rate policy is deflationary/contractionary enough for even a 9% budget deficit not to do much more than support gdp at muddling through levels, with a far too high output gap/unemployment rate.

And falling commodities, weak stocks, and a strong dollar give the Fed that much more reason not to hike.

C. A mixed bag for stocks.

Equity values have fallen after running up on the QE rumor/news, further supported by the dollar weakness that came with the QE rumor news, with the equity sell off now exacerbated by the dollar rally which hurts earnings translations and export prospects.

But a 9% federal deficit is still chugging away, adding to incomes and savings of financial assets, and providing for modest top line growth and ok earnings via cost cutting as well.

Fiscal risks include letting the tax cuts expire and proactive spending cuts by the new Congress which seems committed to austerity type measures.

Low interest rates help valuations but reduce the economy’s interest income.

China acting more like the inflation problem is serious. Hearing talk of price controls, as they struggle to sustain employment and keep a lid on prices, in a nation where inflation or unemployment have meant regime change. Looks to me like a slowdown can’t be avoided with the western educated kids now mostly in charge.

>

> (email exchange)

>

> On Wed, Nov 17, 2010 at 1:05 AM, Paul wrote:

>

> Very interesting — but I have a question:

>

> What if the deficit causes “saving” increase in financial assets held by

> foreigners (via the trade imbalance) rather than US domestic households?

>

Hi Paul!

That would mean we would get the additional benefit of enjoying a larger trade deficit, which means for a given size govt taxes can be that much lower.

Or, if we get sufficient domestic private sector deficit spending, govt deficit spending can remain the same and we benefit by the enhanced real terms of trade supported by the increased foreign savings desires.

Except of course policy makers don’t get it and squander the benefit of a larger trade deficit/better real terms of trade with a too low federal deficit (taxes too high for the given level of govt) that sadly results in domestic unemployment- currently a real cost beyond imagination.

Fundamentally, exports are real costs and imports real benefits, and net imports are a function of foreign savings desires.

So the higher the foreign savings desires the better the real terms of trade.

Also, with floating exchange rates, the way I see it, it’s always ‘in balance’ as the trade deficit = foreign savings desires.

Best!

Warren