[Skip to the end]

Some of governments’ mystery money showed up in sovereign budgets funded by debt sold to investors, but more of it showed up on central bank balance sheets as a result of check writing that required no money at all.

The US govt never has nor doesn’t have dollars. It necessarily spends by changing numbers up in bank accounts, and taxes and borrows by changing numbers down in bank accounts.

The latter was 2009’s global innovation known as “quantitative easing,” where central banks and fiscal agents bought Treasuries, Gilts, and Euroland corporate “covered” bonds approaching two trillion dollars. It was the least understood, most surreptitious government bailout of all, far exceeding the U.S. TARP in magnitude.

Agreed! To the extent the purchases were govt and agency securities it was not a bailout for the issuers. To the extent it allowed investors to make profits from the govt over paying for outstanding securities it could be considered a bailout. But I think that was minimal at best.

In the process, as shown in Chart 1, the Fed and the Bank of England (BOE) alone expanded their balance sheets (bought and guaranteed bonds) up to depressionary 1930s levels of nearly 20% of GDP. Theoretically, this could go on for some time,

Indefinitely. Better still, the tsy could simply stop issuing the securities in the first place, as Charles Goodhart has recommended for the UK. That would save the transactions expenses, which are not trivial.

but the check writing is ultimately inflationary

Not per se. Only to the extent the resultant lower rates are inflationary, and the jury is out on that. Note the Fed just turned $60 billion or so in profits over to the tsy. This is interest income the private sector did not earn because the Fed bought the securities.

Point is, QE removes interest income from the non govt sectors and is thereby a contractionary bias.

and central bankers don’t like to get saddled with collateral such as 30-year mortgages that reduce their maneuverability and represent potential maturity mismatches if interest rates go up.

None of that should matter to central bankers, but agreed it does (for the wrong reasons).

So if something can’t keep going, it stops – to paraphrase Herbert Stein – and 2010 will likely witness an attempted exit by the Fed at the end of March, and perhaps even the BOE later in the year.

It can keep going, but agreed it is likely to stop.

Here’s the problem that the U.S. Fed’s “exit” poses in simple English: Our fiscal 2009 deficit totaled nearly 12% of GDP and required over $1.5 trillion of new debt to finance it. The Chinese bought a little ($100 billion) of that, other sovereign wealth funds bought some more, but as shown in Chart 2, foreign investors as a group bought only 20% of the total – perhaps $300 billion or so. The balance over the past 12 months was substantially purchased by the Federal Reserve. Of course they purchased more 30-year Agency mortgages than Treasuries, but PIMCO and others sold them those mortgages and bought – you guessed it – Treasuries with the proceeds. The conclusion of this fairytale is that the government got to run up a 1.5 trillion dollar deficit, didn’t have to sell much of it to private investors, and lived happily ever – ever – well, not ever after, but certainly in 2009.

I submit it could have easily issued at least that many 3 mo bills if it wanted to but chose not to, again for the wrong reasons.

It also could have issue no securities and simply let the deficit spending sit as additional excess reserves in member bank accounts at the fed, which would be my first choice. Reserve balances are functionally nothing more than one day securities. I see no reason to issue further out the curve and thereby support the term structure of rates at higher levels.

Now, however, the Fed tells us that they’re “fed up,” or that they think the economy is strong enough for them to gracefully “exit,” or that they’re confident that private investors are capable of absorbing the balance.

Yes, in fact, it’s a non event, much like when Japan ‘exited’ from its 30t yen of excess reserves several years ago.

Not likely. Various studies by the IMF, the Fed itself, and one in particular by Thomas Laubach, a former Fed economist, suggest that increases in budget deficits ultimately have interest rate consequences and that those countries with the highest current and projected deficits as a percentage of GDP will suffer the highest increases – perhaps as much as 25 basis points per 1% increase in projected deficits five years forward.

Wonder how they explain Japan with far higher deficits than the us, less QE, and a 10 year JGB of only 1.30% vs 3.80% for the us. The term structure of rates is a function of the combination of anticipated central bank rate settings and technicals. (the three month eurodollar futures add up to the 10 year swap rate, convexity adjusted)

If that calculation is anywhere close to reality,

No reason to think they will be. They aren’t based on reality.

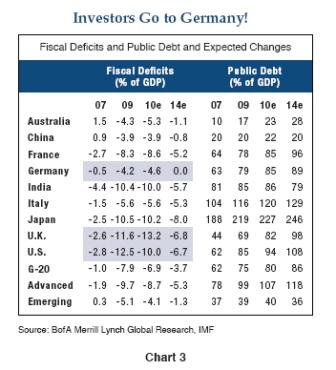

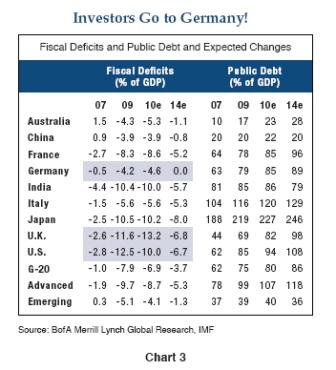

investors can guesstimate the potential consequences by using impartial IMF projections for major G7 country deficits as shown in Chart 3.

Using 2007 as a starting point and 2014 as a near-term destination, the IMF numbers show that the U.S., Japan, and U.K. will experience “structural” deficit increases of 4-5% of GDP over that period of time, whereas Germany will move in the other direction. Germany, in fact, has just passed a constitutional amendment mandating budget balance by 2016.

Hopefully they don’t actually do that as the recession could be severe enough to bring down the entire system of govt.

If these trends persist, the simple conclusion is that interest rates will rise on a relative basis in the U.S., U.K., and Japan compared to Germany over the next several years and that the increase could approximate 100 basis points or more. Some of those increases may already have started to show up – the last few months alone have witnessed 50 basis points of differential between German Bunds and U.S. Treasuries/U.K. Gilts, but there is likely more to come.

The fact is that investors, much like national citizens, need to be vigilant and there has been a decided lack of vigilance in recent years from both camps in the U.S. While we may not have much of a vote between political parties, in the investment world we do have a choice of airlines and some of those national planes may have elevated their bond and other asset markets on the wings of central bank check writing over the past 12 months.

Yes, govt policy, or lack of it, sets the term structure of rates. When it comes to the risk free rate, govt is necessarily price setter, as it is the monopoly supplier of reserves at the margin.

Downdrafts and discipline lie ahead for governments and investor portfolios alike. While my own Pollyannish advocacy of “check-free” elections may be quixotic, the shifting of private investment dollars to more fiscally responsible government bond markets may make for a very real outcome in 2010 and beyond.Additionally, if exit strategies proceed as planned, all U.S. and U.K. asset markets may suffer from the absence of the near $2 trillion of government checks written in 2009.

True!

It seems no coincidence that stocks, high yield bonds, and other risk assets have thrived since early March, just as this “juice” was being squeezed into financial markets. If so, then most “carry” trades in credit, duration, and currency space may be at risk in the first half of 2010 as the markets readjust to the absence of their “sugar daddy.”

True, the curve could steepen some. But at the same time, if the output gap remains high, and it becomes more likely the fed will be low for long, the term structure of rates could decline accordingly, as it did in Japan.

There’s no tellin’ where the money went?

Where it always goes. One account at the Fed is debited and another credited.

Not exactly, but it’s left a suspicious trail. Market returns may not be “so fine” in 2010.

William Gross

Managing Director

[top]