From Mike Green: US weekly jobless claims remain very high given the labor force growth rate

Category Archives: Employment

Comments on Baker/Bernstein book

Seems there’s new full court press on for full employment by the headline left. And they lifted it directly out of what I’ve been posting and publishing at least since ‘Soft Currency Economics’ written in 1993, with editorial assistance by Art Laffer and Mark McNary. And even earlier Professor Bill Mitchell had been independently writing about and urging what he then called buffer stock employment, which he has continued to promote on his widely read blog as the Job Guarantee. In fact, throughout the later 1990’s we co authored and published numerous times on exactly this topic.

In 1996 with the urging and intellectual support of Professor Paul Davidson, I wrote ‘Full Employment and Price Stability’ that was published in the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics and gives a full outline of the current Baker/Bernstein proposal in full detail, including the debits and credits at the Fed that support it. And, at the same time, a supporting math model was published by Professor Pavlina Tcherneva.

In 1998 Professor Randall Wray, a student of Hyman Minsky and one of our original ‘MMT family’, published ‘Understanding Modern Money’ which again outlined the same proposal, which he called ‘the employer of last resort’ (ELR), a term believed to be first used by Professor Minsky.

In 2010, I published ‘The 7 Deadly Innocent Frauds of Economic Policy’ that again promotes an employed labor buffer stock policy, vs today’s policy of using an unemployed labor buffer stock. By that time I had begun framing it as a ‘transition job’ policy, to facilitate the transition from unemployment to private sector employment, recognizing that employers prefer to hire people already working. And directly to the point of this post, a few years ago I met with Dean Baker for at least two hours in his office, after he had read my book, discussing the fine points of the various proposals. Not to mention the continuous stream of research and publications on full employment and the transition job concept by UMKC Professors Mat Forstater and Stephanie Kelton, Professor Scott Fullwiler, and all the UMCK PhD alumni now teaching and publishing globally. Additionally, Professor Jan Kregel published a similar proposal for the euro zone.

I apologize in advance to everyone I’ve inadvertently omitted who have also worked to advance this proposal over the last 20 years.

So with this context please note the following from the new Baker/Bernstein book:

Page 73:

” The second policy idea is to launch a system of publicly funded jobs that can ramp up and down, expand and contract, as needed, in tandem with the business cycle. Under such a system the federal government, working through local intermediaries, would supply funds to subsidize hiring in the private sector as well as in important community services like education, child care, and recreation.”

Page 81:

“Thus, a transitional jobs program, which could offer extra services to hard to employ populations or simply provide a temporary public or subsidized private job to a long term unemployed person, would be a useful component of a strategy of publicly funded jobs. For the long term unemployed, it will be easier to find a permanent job if theyve already got a temporary one”

The promotional page can be found here.

The full book can be found here.

But don’t bother to read the text. It’s highly flawed and ‘out of paradigm’ throughout, and wouldn’t get anywhere near a passing grade in any UMKC classroom.

The only interesting part and the point of this post is the shameless lack of any attribution whatsoever to any of the above mentioned MMT economists for ideas and language ‘copied and pasted’, so to speak.

I recall the critical outcry when MLK was found out to have plagiarized some paper when he was in school and suspect in this case we’ll see the old double standard at work leaving this stone unturned.

Tweet from Stephanie Kelton (@StephanieKelton)

July payrolls revised down to 89,000

July was first initially released at up 162,000 which, while lower than expected, I noted was still inconsistent with low top line growth. That is, without top line growth there aren’t any new private sector jobs unless productivity is negative. And causation runs from sales to employment.

So there’s no reason to expect job growth without top line growth that exceeds underlying productivity increases.

Also, the conventional wisdom all year has been that when govt ‘gets out of the way’ the ‘underlying private sector strength’ will come through and growth will resume. It was noted that reduced job totals were lowered by govt cutbacks while private jobs remained high. I suggested govt employment cutbacks would reduce private sector job growth, as that many fewer govt employees meant that much less spending/sales/employment for the private sector.

Conclusion-

With fiscal support down to less than 3% of GDP from around 7% about a year ago, and at least 1.5% of that from the recent proactive tax hikes and spending cuts, and the automatic fiscal stabilizers as aggressive as they are, and with ‘financial conditions’ as they are, I don’t see any signs of the domestic credit expansion needed to support anything more than

very modest levels of real growth. And I also continue to see substantial risk of negative growth should the housing softness persist, auto sales revert back to the 15 million level, student loan growth continue to decelerate, business investment not accelerate, and net imports not do a lot.

Lower fuel prices are a plus but not yet nearly enough overcome the fiscal hurdles.

(feel free to distribute)

Employment Situation

Released On 10/22/2013 8:30:00 AM For Sep, 2013

Highlights

The payroll data and household numbers were mixed in September at the headline level but soft in detail. Markets were looking over their collective shoulder at the Fed. Total payroll jobs in September advanced 148,000, following a revised increase of 193,000 for August (originally up 169,000) and after a revised gain of 89,000 for July (previous estimate was 104,000). The consensus forecast was for a 184,000 gain for the latest month. The net revisions for July and August were up 9,000.

The unemployment rate slipped to 7.2 percent after dipping to 7.3 percent in August. Analysts expected a 7.3 percent unemployment rate. But the improvement was largely related to a decline in the pool of available workers, affecting the number of unemployed.

Turning back to payroll data, growth in recent months has been on a slowing trend. Private payrolls gained 126,000, following an increase of 161,000 in August (originally 152,000). The median forecast was for a 184,000 rise.

Wage growth eased in September, rising only 0.1 percent for average hourly earnings, following 0.2 percent the month before. Expectations were for a 0.2 percent gain. The average workweek held steady at 34.5 hours, matching the consensus projection

NFP:

Full size image

Private NFP:

Full size image

Y/Y growth in household labor force survey:

Full size image

Comments on Volcker article

Here’s my take on the Volcker article

My comments in below:

The Fed & Big Banking at the Crossroads

By Paul Volcker

I have been struck by parallels between the challenges facing the Federal Reserve today and those when I first entered the Federal Reserve System as a neophyte economist in 1949.

Most striking then, as now, was the commitment of the Federal Reserve, which was and is a formally independent body, to maintaining a pattern of very low interest rates, ranging from near zero to 2.5 percent or less for Treasury bonds. If you feel a bit impatient about the prevailing rates, quite understandably so, recall that the earlier episode lasted fifteen years.

The initial steps taken in the midst of the depression of the 1930s to support the economy by keeping interest rates low were made at the Fed’s initiative. The pattern was held through World War II in explicit agreement with the Treasury. Then it persisted right in the face of double-digit inflation after the war, increasingly under Treasury and presidential pressure to keep rates low.

Yes, and this was done after conversion to gold was suspended which made it possible. And they fixed long rates as well/

The growing restiveness of the Federal Reserve was reflected in testimony by Marriner Eccles in 1948:

Under the circumstances that now exist the Federal Reserve System is the greatest potential agent of inflation that man could possibly contrive.

This was pretty strong language by a sitting Fed governor and a long-serving board chairman. But it was then a fact that there were many doubts about whether the formality of the independent legal status of the central bank—guaranteed since it was created in 1913—could or should be sustained against Treasury and presidential importuning. At the time, the influential Hoover Commission on government reorganization itself expressed strong doubts about the Fed’s independence. In these years calls for freeing the market and letting the Fed’s interest rates rise met strong resistance from the government.

Not freeing the ‘market’ but letting the Fed chair have his way. Rates would be set ‘politically’ either way. Just a matter of who.

Treasury debt had enormously increased during World War II, exceeding 100 percent of the GDP, so there was concern about an intolerable impact on the budget if interest rates rose strongly. Moreover, if the Fed permitted higher interest rates this might lead to panicky and speculative reactions. Declines in bond prices, which would fall as interest rates rose, would drain bank capital. Main-line economists, and the Fed itself, worried that a sudden rise in interest rates could put the economy back in recession.

All of those concerns are in play today, some sixty years later, even if few now take the extreme view of the first report of the then new Council of Economic Advisers in 1948: “low interest rates at all times and under all conditions, even during inflation,” it said, would be desirable to promote investment and economic progress. Not exactly a robust defense of the Federal Reserve and independent monetary policy.

But in my humble opinion a true statement!

Eventually, the Federal Reserve did get restless, and finally in 1951 it rejected overt presidential pressure to maintain a ceiling on long-term Treasury rates. In the event, the ending of that ceiling, called the “peg,” was not dramatic. Interest rates did rise over time, but with markets habituated for years to a low interest rate, the price of long-term bonds remained at moderate levels. Monetary policy, free to act against incipient inflationary tendencies, contributed to fifteen years of stability in prices, accompanied by strong economic growth and high employment. The recessions were short and mild.

I agreed with John Kenneth Galbraith in that inflation was not a function of rates, at least not in the direction they believed, due to interest income channels. However, the rate caps on bank deposits, etc. Did mean that rate hikes had the potential to disrupt those financial institutions and cut into lending, until those caps were removed.

In general, however, the ‘business cycle’ issues are better traced to fiscal balance.

No doubt, the challenge today of orderly withdrawal from the Fed’s broader regime of “quantitative easing”—a regime aimed at stimulating the economy by large-scale buying of government and other securities on the market—is far more complicated. The still-growing size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet imply the need for, at the least, an extended period of “disengagement,” i.e., less active purchasing of bonds so as to keep interest rates artificially low.

Artificially? vs what ‘market signals’? Rates are ‘naturally’ market determined with fixed fx policies, not today’s floating fx.

In fact, without govt ‘interference’ such as interest on reserves and tsy secs, the ‘natural’ rate is 0 as long as there are net reserve balances from deficit spending.

Nor is there any technical or operational reason for unwinding QE. Functionally, the Fed buying securities is identical to the tsy not issuing them and instead letting its net spending remain as reserve balances. Either way deficit spending results in balances in reserve accounts rather than balances in securities accounts. And in any case both are just dollar balances in Fed accounts.

Moreover, the extraordinary commitment of Federal Reserve resources,

‘Resources’? What does that mean? Crediting an account on its own books is somehow ‘using up a resource’? It’s just accounting information!

alongside other instruments of government intervention, is now dominating the largest sector of our capital markets, that for residential mortgages. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to note that the Federal Reserve, with assets of $3.5 trillion and growing, is, in effect, acting as the world’s largest financial intermediator. It is acquiring long-term obligations in the form of bonds and financing those purchases by short-term deposits. It is aided and abetted in doing so by its unique privilege to create its own liabilities.

The Fed creates govt liabilities, aka making payments. That’s its function. And, for example, the treasury securities are the initial intervention. They are paid for by the Fed debiting reserve accounts and crediting securities accounts. All QE does is reverse that as the Fed debits the securities accounts and ‘recredits’ the reserve accounts. So it can be said that all QE does is neutralize prior govt intervention.

The beneficial effects of the actual and potential monetizing of public and private debt, which is the essence of the quantitative easing program, appear limited and diminishing over time. The old “pushing on a string” analogy is relevant. The risks of encouraging speculative distortions and the inflationary potential of the current approach plainly deserve attention.

Right, with the primary fundamental effect being the removal of interest income from the economy. The Fed turned over some $100billion to the tsy that the economy would have otherwise earned. QE is a tax on the economy.

All of this has given rise to debate within the Federal Reserve itself. In that debate, I trust that sight is not lost of the merits—economic and political—of an ultimate return to a more orthodox central banking approach. Concerning possible changes in Fed policy, it is worth quoting from Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s remarks on June 19:

Going forward, the economic outcomes that the Committee sees as most likely involve continuing gains in labor markets, supported by moderate growth that picks up over the next several quarters as the near-term restraint from fiscal policy and other headwinds diminishes. We also see inflation moving back toward our 2 percent objective over time.

If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of [asset] purchases later this year. And if the subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear.

In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7 percent, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains, a substantial improvement from the 8.1 percent unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this program.

I would like to emphasize once more the point that our policy is in no way predetermined and will depend on the incoming data and the evolution of the outlook as well as on the cumulative progress toward our objectives. If conditions improve faster than expected, the pace of asset purchases could be reduced somewhat more quickly. If the outlook becomes less favorable, on the other hand, or if financial conditions are judged to be inconsistent with further progress in the labor markets, reductions in the pace of purchases could be delayed.

Indeed, should it be needed, the Committee would be prepared to employ all of its tools, including an increase in the pace of purchases for a time, to promote a return to maximum employment in a context of price stability.

Implying QE works to do that.

I do not doubt the ability and understanding of Chairman Bernanke and his colleagues. They have a considerable range of instruments available to them to manage the transition, including the novel approach of paying interest on banks’ excess reserves, potentially sterilizing their monetary impact.

Reserves can be thought of as ‘one day treasury securities’ and the idea that paying interest sterilizing anything is a throwback to fixed fx policy, not applicable to floating fx.

What is at issue—what is always at issue—is a matter of good judgment, leadership, and institutional backbone. A willingness to act with conviction in the face of predictable political opposition and substantive debate is, as always, a requisite part of a central bank’s DNA.

A good working knowledge of monetary operations would be a refreshing change as well!

Those are not qualities that can be learned from textbooks. Abstract economic modeling and the endless regression analyses of econometricians will be of little help. The new approach of “behavioral” economics itself is recognition of the limitations of mathematical approaches, but that new “science” is in its infancy.

Monetary operations can be learned from money and banking texts.

A reading of history may be more relevant. Here and elsewhere, the temptation has been strong to wait and see before acting to remove stimulus and then moving toward restraint. Too often, the result is to be too late, to fail to appreciate growing imbalances and inflationary pressures before they are well ingrained.

Those who know monetary operations read history very differently from those who have it wrong.

There is something else that is at stake beyond the necessary mechanics and timely action. The credibility of the Federal Reserve, its commitment to maintaining price stability, and its ability to stand up against partisan political pressures are critical. Independence can’t just be a slogan. Nor does the language of the Federal Reserve Act itself assure protection, as was demonstrated in the period after World War II. Then, the law and its protections seemed clear, but it was the Treasury that for a long time called the tune.

And didn’t do a worse job.

In the last analysis, independence rests on perceptions of high competence, of unquestioned integrity, of broad experience, of nonconflicted judgment and the will to act. Clear lines of accountability to Congress and the public will need to be honored.

And a good working knowledge of monetary operations.

Moreover, maintenance of independence in a democratic society ultimately depends on something beyond those institutional qualities. The Federal Reserve—any central bank—should not be asked to do too much, to undertake responsibilities that it cannot reasonably meet with the appropriately limited powers provided.

I know that it is fashionable to talk about a “dual mandate”—the claim that the Fed’s policy should be directed toward the two objectives of price stability and full employment. Fashionable or not, I find that mandate both operationally confusing and ultimately illusory. It is operationally confusing in breeding incessant debate in the Fed and the markets about which way policy should lean month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter with minute inspection of every passing statistic. It is illusory in the sense that it implies a trade-off between economic growth and price stability, a concept that I thought had long ago been refuted not just by Nobel Prize winners but by experience.

The Federal Reserve, after all, has only one basic instrument so far as economic management is concerned—managing the supply of money and liquidity.

Completely wrong. With floating fx, it can only set rates. It’s always about price, not quantity.

Asked to do too much—for example, to accommodate misguided fiscal policies, to deal with structural imbalances, or to square continuously the hypothetical circles of stability, growth, and full employment—it will inevitably fall short. If in the process of trying it loses sight of its basic responsibility for price stability, a matter that is within its range of influence, then those other goals will be beyond reach.

Back in the 1950s, after the Federal Reserve finally regained its operational independence, it also decided to confine its open market operations almost entirely to the short-term money markets—the so-called “Bills Only Doctrine.” A period of remarkable economic success ensued, with fiscal and monetary policies reasonably in sync, contributing to a combination of relatively low interest rates, strong growth, and price stability.

Yes, and the price of oil was fixed by the Texas railroad commission at about $3 where it remained until the excess capacity in the US was gone and the Saudis took over that price setting role in the early 70’s.

That success faded as the Vietnam War intensified, and as monetary and fiscal restraints were imposed too late and too little. The absence of enough monetary discipline in the face of the overt inflationary pressures of the war left us with a distasteful combination of both price and economic instability right through the 1970s—a combination not inconsequentially complicated further by recurrent weakness in the dollar.

No mention of a foreign ‘monopolist’ hiking crude prices from 3 to 40?

Or of Carter’s deregulation of nat gas in 78 causing OPEC to drown in excess capacity in the early 80’s?

Or the non sensical targeting of borrowed reserves that worked only to shift rate control from the FOMC to the NY fed desk, and prolonged the inflation even as oil prices collapsed?

We cannot “go home again,” not to the simpler days of the 1950s and 1960s. Markets and institutions are much larger, far more complex. They have also proved to be more fragile, potentially subject to large destabilizing swings in behavior. There is the rise of “shadow banking”—the nonbank intermediaries such as investment banks, hedge funds, and other institutions overlapping commercial banking activities.

Not to mention restaurants letting people eat before they pay for their meals. This completely misses the mark.

Partly as a result, there is the relative decline of regulated commercial banks, and the rapid innovation of new instruments such as derivatives. All these have challenged both central banks and other regulatory authorities around the developed world. But the simple logic remains; and it is, in fact, reinforced by these developments. The basic responsibility of a central bank is to maintain reasonable price stability—and by extension to concern itself with the stability of financial markets generally.

In my judgment, those functions are complementary and should be doable.

They are, but it all requires an understanding of the underlying monetary operations.

I happen to believe it is neither necessary nor desirable to try to pin down the objective of price stability by setting out a single highly specific target or target zone for a particular measure of prices. After all, some fluctuations in prices, even as reflected in broad indices, are part of a well-functioning market economy. The point is that no single index can fully capture reality, and the natural process of recurrent growth and slowdowns in the economy will usually be reflected in price movements.

With or without a numerical target, broad responsibility for price stability over time does not imply an inability to conduct ordinary countercyclical policies. Indeed, in my judgment, confidence in the ability and commitment of the Federal Reserve (or any central bank) to maintain price stability over time is precisely what makes it possible to act aggressively in supplying liquidity in recessions or when the economy is in a prolonged period of growth but well below its potential.

With floating fx bank liquidity is always infinite. That’s what deposit insurance is all about.

Again, this makes central banking about price and not quantity.

—

Feel free to distribute.

George Osborne to target unemployed

Why not start by making it voluntary?

That is, just offer a job to anyone willing and able to work and see what happens.

George Osborne to target unemployed in speech

By Katrina Bishop

September 30 (CNBC) — U.K. Treasury Chief George Osborne unveiled plans to overhaul unemployment benefits on Monday, as he attempts to boost his party’s standing in the polls.

Speaking at the Conservative Party Conference in Manchester, Osborne said that those who have been out of work for three years will have to take part in a new government scheme – or risk losing their welfare benefits.

Fed up date

So we know QE is about signaling.

And the Fed knew that tapering was a signal they were ok with the higher rates, including the already higher mortgage rates.

And they decided they didn’t want to send that signal, so they delayed the taper. They also revised down their growth forecasts, which meant the economy was performing at less than expected levels, which further pushed back against the higher rates.

And they expressed risk of continued ‘fiscal drag’ as well. It’s all about signaling their current reaction function to control the term structure of rates. And in fact the rates in question have subsequently come down, indicating tactical success. And, at least for now, the dollar is down a touch as well.

A few interesting things are not part of the discussion:

The Fed can directly set the term structure of their risk free rates by simply making a locked market on any part of the curve.

The Fed buying tsy secs is functionally the same as the tsy not issuing them in the first place.

The consequences of QE/tapering are largely the same as the issuance/non issuance of tsy secs.

Interest rate tools, operationally, also include the tsy issuing only at pre determined rates and maturities, as well as buy backs and maturity swaps.

And why is the paradox of thrift, a mainstream standard for maybe 200 years, never discussed?

By identity, if govt cuts back on its net spending, that output only gets sold if some other agent increases its net spending.

Meanwhile, the demand leakages continue to grow relentlessly. It’s all implicit in every mainstream model, but none the less left out of every public discussion.

And there’s another issue that’s internally conflicted. The Fed believes inflation is about monetary policy and the Fed, and not fiscal policy and the treasury. Hike rates until the ‘real rate’ is high enough and inflation goes down, because it makes borrowing expensive and slows the economy as well.

And lower the real rate enough and inflation goes up, though unfortunately that pesky 0 bound limits that tool, resulting in a hand off to QE and forward guidance and expanding the types of assets the Fed buys and the like.

Not to mention the key is the inflation expectations channel, which rules all, of course.

Let me conclude that today most mainstream elites have recognized there is no solvency risk for the US govt. Simplistically, ‘they can always print the money’ which is good enough for the point at hand. So with no solvency risk, the risk of too high deficits comes down to inflation, and there are no credible long term inflation forecasts flashing red.

Additionally, the Fed believes inflation is a monetary and not fiscal phenomenon. So the Fed can’t even argue against deficits on inflationary grounds, leaving it with, for all practical purposes, no argument for deficit reduction.

So as we enter the fray over deficit reduction and the risk of catastrophic systemic failure, there is no intellectual leadership coming from the Fed, and an intellectually dishonest silence from the mainstream academic and media elite.

Good luck to us!

(feel free to distribute)

homes for sale vs labor participation rate

Interesting chart- inventory of existing homes for sale vs the labor force participation rate…

new home sales track closely as well…

;)

As we used to say, sometimes it’s all one piece…

Full size image

Total US Family Mortgages Outstanding

Looks something like the labor force participation rate…

Real GDP, income, and consumption per capita no great shakes either.

Full size image

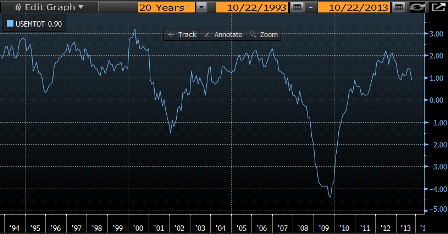

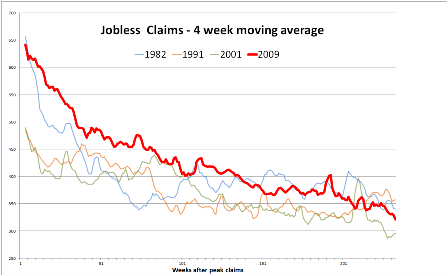

Jobless claims as a function of time

So I have this theory that claims have more to do with time since the peak than with the ‘robustness’ of the recovery.

Claims come from separations, so after economies stop getting worse they ‘quiet down’ over time with regards to jobs lost, even though there may or may not be a lot of ‘new hires’ and expansion, etc.

The chart isn’t adjusted for population, or the size of the labor force, as I’m mainly interested in ‘shape’.

And this can at least partially explain why claims have come down nicely and continue to fall some even as new hires aren’t doing all that well.

Full size image