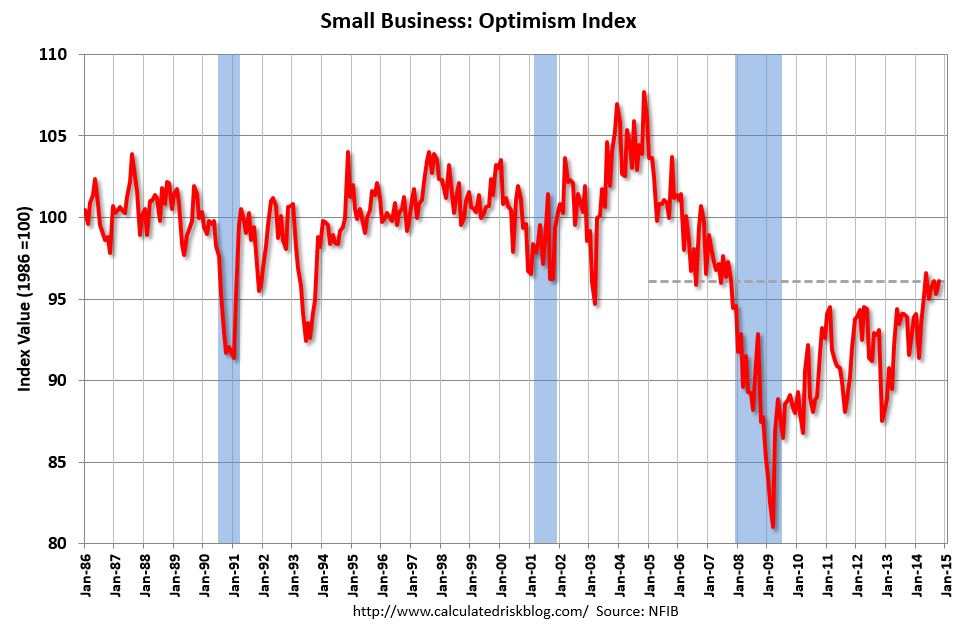

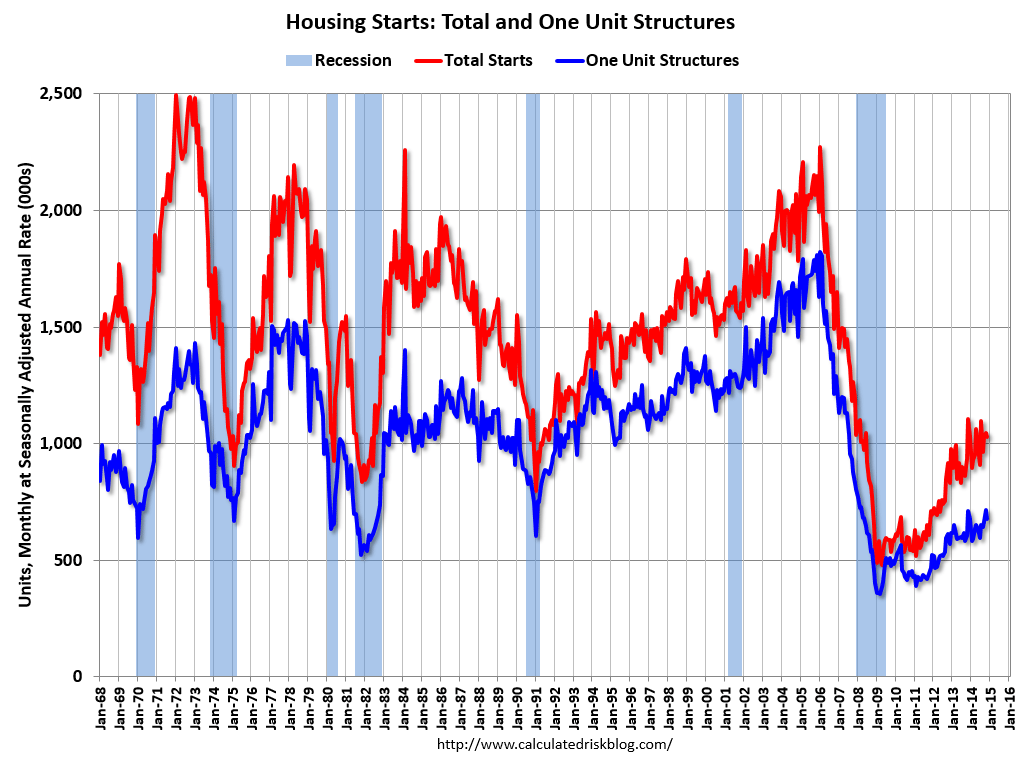

Looks bad to me. Remember, for GDP to grow at last year’s rate, all the pieces on average have to contribute that much. And, as previously discussed, hard to see how starts and sales can grow with cash buyers and mtg purchase apps declining year over year.

The charts look like we are well past this cycle’s peak and headed into negative territory. Not to mention multifamily had been leading the way and those units tend to be smaller/cheaper, so if you were to look at the $ being invested vs prior cycles it would look even worse.

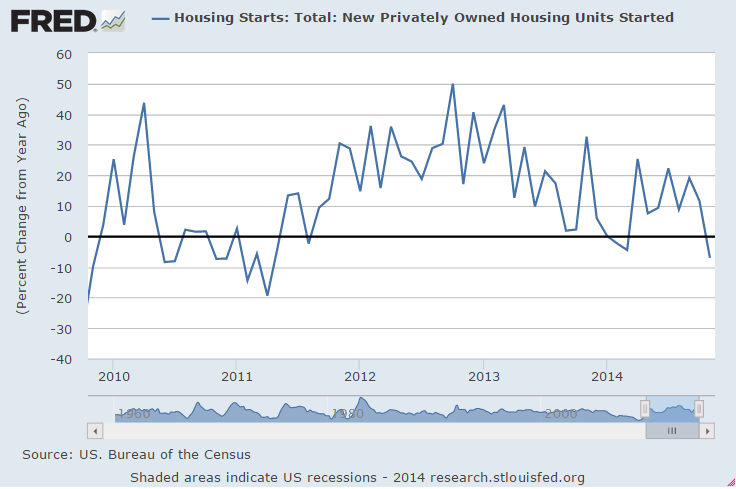

Housing Starts

Highlights

Housing remains on a flat trajectory. Single-family starts and multifamily starts moved in opposite directions. Housing starts dipped 1.6 percent after rebounding 1.7 percent in October. Analysts projected a 1.038 million pace for November. The 1.028 million unit pace was down 7.0 percent on a year-ago basis.

November strength was in the volatile multifamily component. Multifamily starts rebounded 6.7 percent after declining 9.9 percent in October. In contrast, single-family starts fell 5.4 percent in November after gaining 8.0 percent in October.

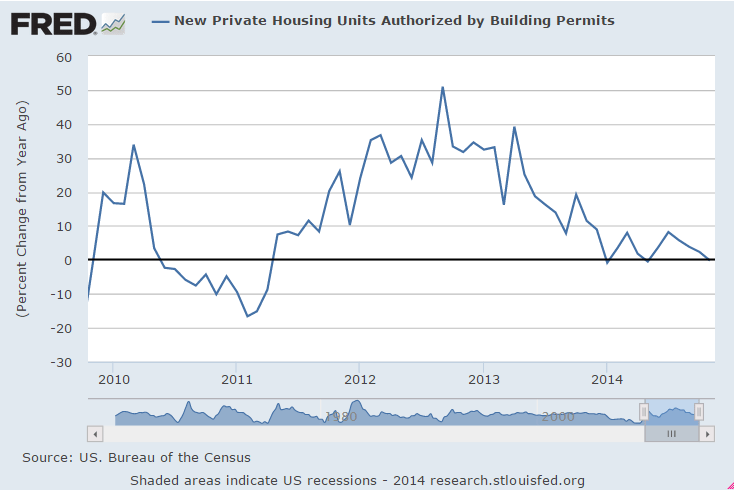

Housing permits declined a monthly 5.2 percent, following a 5.9 percent jump in October. The 1.035 million unit pace was down 0.2 percent on a year-ago basis. Market expectations were for 1.060 million units annualized.

Overall, recent housing numbers have oscillated notably. October was relatively good but November was not. On average, housing growth appears to be flat to modestly positive.

And how about this headline? Make any sense to you?

Japan’s got issues, but ability to ‘service it’s yen debt’ isn’t one of them, as it’s just a matter of debiting securities accounts at the BOJ/by the BOJ and crediting member bank accounts also at the BOJ. But markets don’t seem to quite believe that:

Meanwhile, Japan’s ‘depreciate your currency to prosperity’ policy combined with tax hikes on domestic consumers- about as ‘pro exporter at the expense of most everyone else’- is producing the outcomes previously discussed. They include falling real domestic incomes/real standards of living, increased exporter margins/sales/profits, etc. And more to come, seems, under the ‘no matter how much I cut off it’s still too short, said the carpenter’ mantra now practiced globally.

A few anecdotes:

The day after his ruling coalition secured more than two-thirds of the seats in parliament’s lower house, Mr. Abe acknowledged at a news conference that higher stock prices and corporate profits under his administration have yet to translate into worker gains.

“As I toured around the nation during the election, I heard the opinions of ordinary citizens who are suffering from price increases and small-business owners in difficulties due to price hikes in raw materials,” Mr. Abe said, adding that he will draft an economic stimulus package by the end of the year.

For the second year in a row, the conservative prime minister and his historically pro-business Liberal Democratic Party find themselves in the position of imploring corporations to cut into their profits and give workers more. Mr. Abe said he would summon executives and labor leaders to a meeting Tuesday to make his pitch ahead of next spring’s annual wage talks.

The reason: If wages don’t rise as quickly as prices, households could cut back on spending, endangering an economic recovery. There have only been four months since Mr. Abe took power in December 2012 when real wages—the value of paychecks after accounting for inflation—have risen. A weaker yen has made imported food and other goods more expensive, and a rise in the national sales tax to 8% in April from 5% hit consumers further.

While wages have gone up in nominal terms this year, rising prices — partly the result of a consumption tax hike in April — have negated those gains. Adjusted for inflation, total cash earnings fell 2.8% on the year in October, dropping for a 16th straight month. Unions hope that with this month’s lower house election shaping up to be partly a referendum on Abenomics, the prime minister’s plan for ending deflation, Japan will see a serious debate on wage growth.

The corporate sector is coming to terms with the need to raise pay to some degree next spring.

“What is important is escaping the deflation that has persisted for 15 years,” Sadayuki Sakakibara, chairman of the Keidanren business lobby, told reporters Wednesday.

“Companies that have succeeded in growing their profits ought to reflect that success in their wage increases,” he added.

For the second year in a row, Keidanren will explicitly encourage member companies to raise wages in its guidance for the spring’s “shunto” negotiations.

But even as big export-driven manufacturers cruise toward record profits, many smaller companies, particularly those dependent on domestic demand, are suffering the side effects of a weak yen and still waiting for consumer spending to recover from the tax hike.

China continues to go down the tubes and the western educated hot shots keep pushing the tight fiscal and what they think is ‘loose monetary’ policy that’s failed every time it’s been tried in the history of the galaxy:

Operating conditions deteriorate for the first time since May

(Markit) — Flash China Manufacturing PMI slipped to 49.5 in December from 50.0 in November. Manufacturing Output Index ticked up to 49.7 from 49.6. New Orders decreased while New Export Orders increased at a faster rate. “The HSBC China Manufacturing PMI dropped to a seven-month low of 49.5 in the flash reading for December, down from 50.0 in November. Domestic demand slowed considerably and fell below 50 for the first time since April 2014. Price indices also fell sharply. The manufacturing slowdown continues in December and points to a weak ending for 2014. The rising disinflationary pressures, which fundamentally reflect weak demand, warrant further monetary easing in the coming months.”

Not good here either:

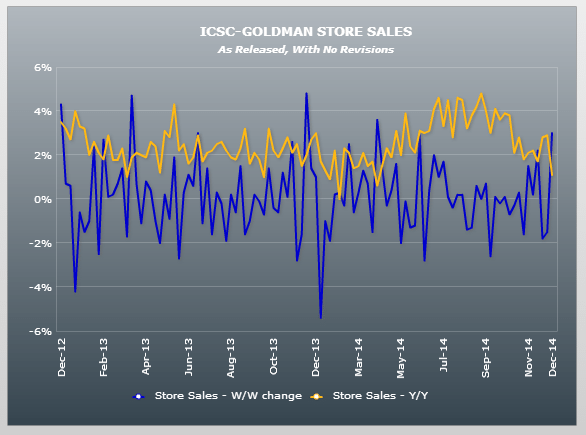

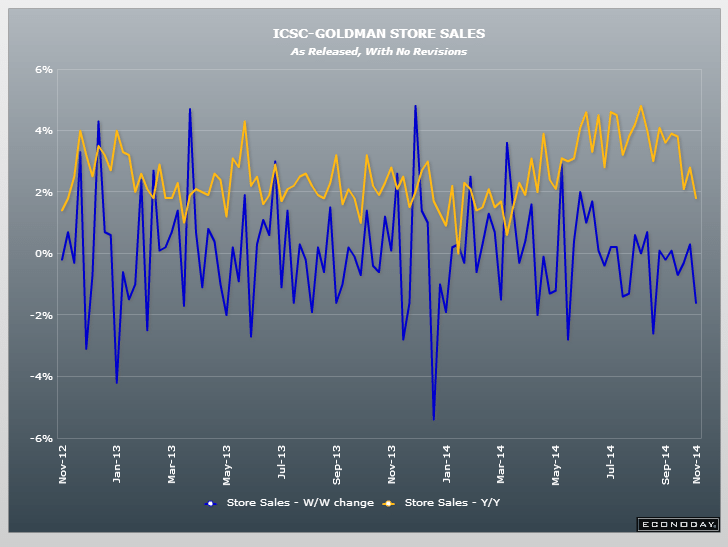

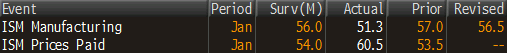

And this came out. Note the year over year trend.