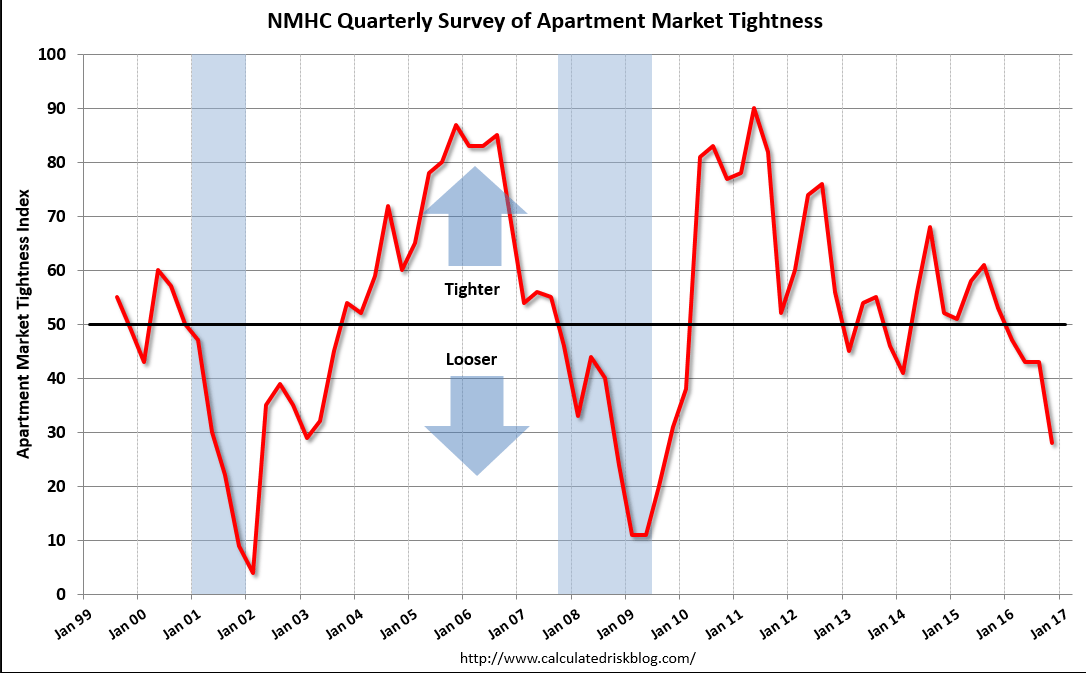

From the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC): Apartment Markets Soften in the January NMHC Quarterly Survey

— Apartment markets continued to retreat in the January National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) Quarterly Survey of Apartment Market Conditions. All four indexes of Market Tightness (25), Sales Volume (25), Equity Financing (33) and Debt Financing (14) remained below the breakeven level of 50 for the second quarter in a row.

“Weaker conditions are evident across all sectors as the apartment industry adjusts to changing conditions,” said Mark Obrinsky, NMHC’s Senior Vice President of Research and Chief Economist. “Rising supply—particularly during a seasonally weak quarter—is causing rent growth to moderate in many markets. At the same time, the sharp rise in interest rates in recent months was a triple whammy for the industry. First, higher rates directly worsen debt financing conditions. Second, the associated rise in cap rates also put a crimp in sales of apartment properties. Third, higher cap rates following the long run-up in apartment prices caused greater caution among equity investors.”

Read more at http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/#2WgZcWzbFIxpsveW.99

TRUMP’S VAINGLORIOUS AFFRONT TO THE C.I.A.

By Robin Wright

Jan 22 (The New Yorker) — The President’s remarks to the C.I.A. on Saturday, delivered in front of a hallowed memorial, stirred anger and astonishment among current and former agency officials.

The death of Robert Ames, who was America’s top intelligence officer for the Middle East, is commemorated among the hundred and seventeen stars on the white marble Memorial Wall at C.I.A. headquarters, in Langley, Virginia. He served long years in Beirut; Tehran; Sanaa, Yemen; Kuwait City; and Cairo, often in the midst of war or turmoil. Along the way, Ames cultivated pivotal U.S. operatives and sources, even within the Palestine Liberation Organization when it ranked as the world’s top terrorist group. In April, 1983, as chief of the C.I.A.’s Near East division, back in Washington, Ames returned to Beirut for consultations as Lebanon’s civil war raged.

Shortly after 1 p.m. on April 18th, 1983, Ames was huddling with seven other C.I.A. staff at the high-rise U.S. Embassy overlooking the Mediterranean, when a delivery van laden with explosives made a sharp swing into the cobblestone entryway, sped past a guard station, and accelerated into the embassy’s front wall. It set off a roar that echoed across Beirut. My office was just up the hill. A huge black cloud enveloped blocks.

It was the very first suicide bombing against the United States in the Middle East, and the onset of a new type of warfare. Carried out by an embryonic cell of extremists that later evolved into Hezbollah, it blew off the front of the embassy, leaving it like a seven-story, open-faced dollhouse. Sixty-four were killed, including all eight members of the C.I.A. team. It was, at the time, the deadliest attack on an American diplomatic facility anywhere in the world, and it remains the single deadliest attack on U.S. intelligence. (Only one of the thirty attacks on U.S. missions since then, in Nairobi, in 1998, has been deadlier.)

Ryan Crocker, the embassy’s political officer, had met with Ames earlier that day. Crocker was blown against the wall by the bomb’s impact, but escaped serious injury. He spent hours navigating smoke, fires, and tons of concrete, steel, and glass debris, searching for his colleagues.

“This is seared into my mind, irretrievably,” Crocker recalled for me this weekend. “There wasn’t an organized recovery plan, not in the initial hours after the bombing. I was de facto in charge that first awful night, when you dug a little and shouted out in case there was someone alive there, and then dug a bit more. Somewhere that night, I was on that rubble heap, and a radiator caught my eye. There was an object at the foot of the radiator. It looked like a beach ball, covered thick with dust. It was Bob Ames’s head.”

Ames left behind a widow and six children. He was so clandestine that his kids did not know that he was a spy until after he was killed. President Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy, saw the flag-draped coffins of the American victims arrive at Andrews Air Force Base, and met with the families of the deceased.

Reagan, who had known Ames, recounted the meetings in his diary, according to Kai Bird’s book about Ames, “The Good Spy”: “We were both in tears—I know all I could do was grip their hands—I was too choked up to speak.” More than three thousand people turned out for the memorial service at the National Cathedral for Ames and the other American victims.

On his first full day in office, President Trump spoke at the C.I.A. headquarters in front of the hallowed Memorial Wall, with Ames’s star on it. Since his election, Trump has raged at the U.S. intelligence community over its warnings about Russian meddling in the Presidential election. After CNN reported on, and BuzzFeed published, an as-yet unsubstantiated dossier about Trump’s ties to Russia and personal behavior, the President erupted on Twitter, “Intelligence agencies should never have allowed this fake news to ‘leak’ into the public. One last shot at me. Are we living in Nazi Germany?”

On Saturday, speaking to about four hundred intelligence officials, Trump blamed any misunderstanding on the media. “They are among the most dishonest human beings on Earth,” he said. (The official White House transcript notes “laughter” and “applause” here.) “They sort of made it sound like I had a feud with the intelligence community. And I just want to let you know, the reason you’re the No. 1 stop is exactly the opposite—exactly.”

Trump vowed greater support for America’s sixteen intelligence agencies than they had received from any other President. “Very, very few people could do the job you people do,” he said. “I know maybe sometimes you haven’t gotten the backing that you’ve wanted, and you’re going to get so much backing. Maybe you’re going to say, Please don’t give us so much backing. Mr. President, please, we don’t need that much backing.” Trump said he assumed that “almost everybody” in the cavernous C.I.A. entry hall had voted for him, “because we’re all on the same wavelength, folks.”

In his remarks, Trump made passing reference to the “special wall” behind him but never mentioned the top-secret work or personal sacrifices of intelligence officers like Ames and the others who died in Beirut, including the C.I.A. station chief Kenneth Haas, and James F. Lewis, who had been a prisoner of war in North Vietnam, and his wife Monique, who was on her first day on the job at the Beirut embassy. Nor did the President refer to any of the dozens of others for whom stars are etched on the hallowed C.I.A. wall of honor. It was like going to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and not mentioning those who died in the Second World War.

Trump’s unscripted remarks were, instead, largely about himself, even as he praised Mike Pompeo—a West Point and Harvard Law School graduate, Kansas congressman, and Tea Party supporter—as his choice to lead the C.I.A.

“No. 1 in his class at West Point,” Trump said. “Now, I know a lot about West Point. I’m a person that very strongly believes in academics. In fact, every time I say I had an uncle who was a great professor at M.I.T. for thirty-five years, who did a fantastic job in so many different ways, academically—was an academic genius—and then they say, Is Donald Trump an intellectual? Trust me, I’m like a smart person.”

Apparently as proof, the President noted that he had set an “all-time record” in Time magazine cover stories. “Like, if Tom Brady is on the cover, it’s one time, because he won the Super Bowl or something, right?” he told the intelligence officials. “I’ve been on it for fifteen times this year. I don’t think that’s a record that can ever be broken.” Time told Politico’s Playbook that it had published eleven Trump covers—and had done fifty-five cover stories about Richard Nixon.

Trump spoke briefly about eradicating “radical Islamic extremism,” a cornerstone of his foreign policy. But he devoted more than twice as many words to the dispute over the turnout at his Inauguration. “Did everybody like the speech?” Trump asked. “I’ve been given good reviews. But we had a massive field of people. You saw them. Packed. I get up this morning, I turn on one of the networks, and they show an empty field. I say, wait a minute, I made a speech. I looked out, the field was—it looked like a million, million and a half people.”

Crowd scientists who spoke to the Times estimated that about a hundred and sixty thousand people attended, compared with the record-setting 1.8 million who were estimated to have been at President Obama’s first Inauguration. Trump was defiant. “We caught them, and we caught them in a beauty,” he told the C.I.A. crowd. “And I think they’re going to pay a big price.”

Trump’s remarks caused astonishment and anger among current and former C.I.A. officials. The former C.I.A. director John Brennan, who retired on Friday, called it a “despicable display of self-aggrandizement in front of C.I.A.’s Memorial Wall of Agency heroes,” according to a statement released through a former aide. Brennan said he thought Trump “should be ashamed of himself.”

Crocker, who was among the last to see Ames and the local C.I.A. team alive in Beirut, was “appalled” by Trump’s comments. “Whatever his intentions, it was horrible,” Crocker, who went on to serve as the U.S. Ambassador in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, and Kuwait, told me. “As he stood there talking about how great Trump is, I kept looking at the wall behind him—as I’m sure everyone in the room was, too. He has no understanding of the world and what is going on. It was really ugly.”

“Why,” Crocker added, “did he even bother? I can’t imagine a worse Day One scenario. And what’s next?”

John McLaughlin is a thirty-year C.I.A. veteran and a former acting director of the C.I.A. who now teaches at Johns Hopkins University. He also chairs a foundation that raises funds to educate children of intelligence officers killed on the job. “It’s simply inappropriate to engage in self obsession on a spot that memorializes those who obsessed about others, and about mission, more than themselves,” he wrote to me in an e-mail on Sunday. “Also, people there spent their lives trying to figure out what’s true, so it’s hard to make the case that the media created a feud with Trump. It just ain’t so.”

John MacGaffin, another thirty-year veteran who rose to become the No. 2 in the C.I.A. directorate for clandestine espionage, said that Trump’s appearance should have been a “slam dunk,” calming deep unease within the intelligence community about the new President. According to MacGaffin, Trump should have talked about the mutual reliance between the White House and the C.I.A. in dealing with global crises and acknowledged those who had given their lives doing just that.

“What self-centered, irrational decision process got him to this travesty?” MacGaffin told me. “Most importantly, how will that process serve us when the issues he must address are dangerous and incredibly complex? This is scary stuff!”

Trump could have taken a page from Reagan, whom he has often invoked. In 1984, at a groundbreaking ceremony for an addition to C.I.A. headquarters, Reagan told the intelligence community, “The work you do each day is essential to the survival and to the spread of human freedom. You remain the eyes and ears of the free world. You are the ‘trip wire’ over which totalitarian rule must stumble in their quest for global domination. . . . From Nathan Hale’s first covert operation in the Revolutionary War to the breaking of the Japanese code at Midway in World War II, America’s security and safety have relied directly on the courage and collective efforts of her intelligence personnel.”

Bruce Riedel was a protégé of Ames at the C.I.A.; they travelled together in the Middle East. For more than three decades, he has made an annual visit to Ames’s grave at Arlington National Cemetery. He noted one glaring omission from Trump’s comments: a third of the stars are from deaths that have happened since 9/11, “making it more dangerous to work for the agency now than ever before.” He faulted Trump for not visiting the Counterterrorism Center, talking to the team now tracking Al Qaeda and Islamic State leaders, and seeing how drones work—all “invaluable experience when he later needs to make life-and-death decisions,” Riedel, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told me.

Paul Pillar, a Vietnam veteran, rose to become deputy director of the Counterterrorism Center and later the National Intelligence Officer in charge of the Middle East and South Asia. He, too, was anguished by Trump’s comments. “He used the scene as a prop for another complaint about the media and another bit of braggadocio about his crowds and his support,” Pillar told me Sunday. “That the specific prop was the C.I.A.’s memorial wall, and that Trump made no mention of those whom that wall memorializes, made his performance doubly offensive.”

At 7:35 a.m. on Sunday, Trump responded on Twitter to the negative reactions to his comments. “Had a great meeting at CIA Headquarters yesterday, packed house, paid great respect to Wall, long standing ovations, amazing people. WIN!”

But it’s hard to see how America’s new leader will recoup from a performance so shallow, irreverent, and vainglorious.