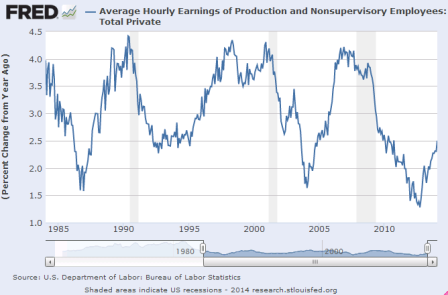

Wage spike!

Inflation!

Better tighten up quick!!!

:(

Full size image

First, the growth rate is still low and from this chart could be leveling off.

Second, for a 40 hour week the average gross wage is only just over $800/week!

Third, the growth rate is not inflation adjusted!

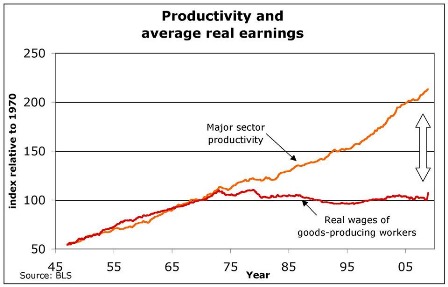

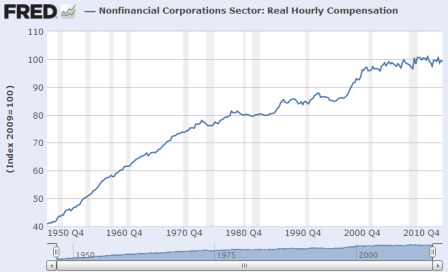

Fourth, the wage share has been falling for decades as productivity increases have gone elsewhere.

And what makes anyone think any of this is a function of interest rates?

Particularly in the direction assumed?

And why is it assumed that increased wages wouldn’t cut into profit margins?

Is the economy assumed to be ‘competitive’ only when it suites?

;)

So my narrative is:

The Federal budget deficit is too small to support growth given the current ‘credit environment’- maybe $400b less net spending in 2014. The automatic fiscal stabilizers are ‘aggressive’, as they materially and continually reduce the deficit it all turns south. The demand leakages are relentless, including expanding pension type assets, corporate/insurance accumulations, foreign CB $ accumulation, etc. etc.

The Jan 2013 FICA hike and subsequent sequesters took maybe 2% off of GDP as they flattened the prior growth rates of housing, cars, retail sales, etc. etc. Q3/Q4 GDP was suspect due to inventory building, a net export ‘surge’, and a ‘surge’ in year end construction spending/cap ex etc. I suspected these would ‘revert’ in H1 2014. It was a very cold winter that slowed things down, followed by a ‘make up’ period. The question now is where it all goes from there. For every component growing slower than last year, another has to be growing faster for the total to increase.

The monthly growth rate of durable goods orders fell off during the cold snaps and the worked it’s way back up, though still not all the way back yet, and the ‘ex transportation’ growth rate was bit lower:

And of note:

Investment in equipment eased after a robust March. Nondefense capital goods orders excluding aircraft dipped 1.2 percent, following a 4.7 percent jump in March. Shipments for this series slipped 0.4 percent after gaining 2.1 percent the prior month.

In general the manufacturing surveys were firm.

Mortgage purchase applications continued to come in substantially below last year, even with the expanded, more representative survey:

According to the MBA, the unadjusted purchase index is down about 15% from a year ago.

MBA Mortgage Applications

Highlights

Mortgage applications for home purchases remain flat, down 1.0 percent in the May 23 week to signal weakness for underlying home sales. Refinancing applications, which had been showing life in prior weeks tied to the dip underway in mortgage rates, also slipped 1.0 percent in the week. Mortgage rates continue to edge lower, down 2 basis points for 30-year conforming loans ($417,000 or less) to 4.31 percent and the lowest average since June last year.

And then there was the Q1 revised GDP release:

What drove it negative was a decline in inventories, net exports, and construction/cap ex:

The largest revisions to the headline number were from inventories (revised downward by -1.05%) and imports (down -0.36%), and although exports improved somewhat from the prior report, they still subtracted -0.83% from the headline. Fixed investments in both equipment and residential construction continued to contract.

PCE growth was revised up to +3.1% (adding 2.09% to GDP) but seems over 1% of that came from ACA (Obamacare) related and other non discretionary expenditures like heating expenses, etc. The question then is whether the increases will continue at that rate and whether the increased ACA related expenses will eat into other, discretionary expenditures.

The contribution made by consumer services spending remained essentially the same at 1.93% (up 0.36% from the 1.57% in the prior quarter). As mentioned last month, the increased spending was primarily for non-discretionary healthcare, housing, utilities and financial services – i.e., increased expenses that stress households without providing any perceived improvement to their quality of life.

And seems this Chart is consistent with my narrative:

And not that it matters, but just an interesting observation:

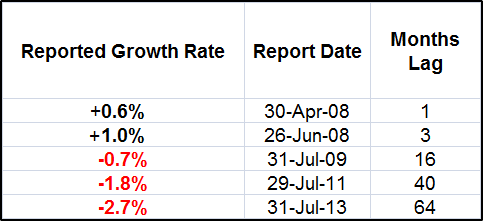

And lastly, for this report the BEA assumed annualized net aggregate inflation of 1.28%. During the first quarter (i.e., from January through March) the growth rate of the seasonally adjusted CPI-U index published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) was over a half percent higher at a 1.80% (annualized) rate, and the price index reported by the Billion Prices Project (BPP – which arguably reflected the real experiences of American households while recording sharply increasing consumer prices during the first quarter) was over two and a half percent higher at 3.91%. Under reported inflation will result in overly optimistic growth data, and if the BEA’s numbers were corrected for inflation using the BLS CPI-U the economy would be reported to be contracting at a -1.52% annualized rate. If we were to use the BPP data to adjust for inflation, the first quarter’s contraction rate would have been a staggering -3.64%.

And looks like this will be limiting the next quarter:

Real per-capita annual disposable income grew by $95 during the quarter (a 1.03% annualized rate). But that number is down a material -$227 per year from the fourth quarter of 2012 (before the FICA rates normalized) and it is up only about 1% in total ($359 per year) since the second quarter of 2008 – some 23 quarters ago.

And remember this?

So the question is, how strong will the Q2 recovery be, and where does it go from there?

Again, looks to me like the deficit is having trouble keeping up with the demand leakages, and it keeps getting harder with time?

Jobless claims continue to work their way lower, but they are a bit of a lagging indicator and even with 0 claims there aren’t necessarily any new hires, either, for example.

And there’s another couple of issues at work here.

First, 1.2 million people lost benefits at year end, and it’s expected up to half of them will find ‘menial’ jobs during H1. However, corporations don’t add to head count just because unskilled workers lose benefits, so the employment numbers may thus be ‘front loaded’ with higher numbers of hires in H1, followed by fewer hires in H2.

Second, seems the new jobs don’t pay a whole lot, and a lot of higher paying jobs continue to be lost, so the increased employment isn’t associated with the kind of subsequent growth multipliers of past cycles.

Corporate profits were down over 10% in the Q1 GDP report, and mainly in the smaller companies as the S&P earnings saw a modest increase. Hence the small caps under performing, for example? Not mention earnings also tend to up and down with the Federal deficit:

This year over year pending home sales chart speaks for itself:

Another series following the pattern- down for the winter weather, then back up some, and this time then backing off some:

Highlights

Personal income & spending, up 0.3 percent and down 0.1 percent, fell back in April following especially strong gains in March. Wages & salaries slowed to plus 0.2 percent vs a 0.6 percent surge in March while spending on durables, reflecting a pause in auto sales, fell 0.5 percent vs gains of 3.6 and 1.3 percent in the prior two months. Spending on services, however, also fell, down 0.2 percent on a decline in utilities and healthcare after a 0.5 percent rise in March. In real terms, spending fell 0.3 percent following the prior month’s 0.8 percent surge. Price data remain muted, up 0.2 percent overall and up 0.2 percent ex-food and energy. Year-on-year price rates are at plus 1.6 percent and 1.4 percent for the core.

And again, the ACA and other non discretionaries added about 1% in Q1. So, again, it’s down for the winter, then up and this time back down to begin Q2 (with the growth of healthcare expenses backing off some):

Federal budget process: What did Leon Panetta mean?

By Duane Catlett and Dan Metzger

May 19 (IR) — Leon Panetta was recently the guest lecturer at the University of Montana’s annual Jones-Tamm Judicial Lecture. Mr. Panetta is a true patriot, having served with distinction for more than 20 years under two presidents. Under President Clinton he directed the Office of Management and Budget and later served as Clinton’s chief of staff. Under President Obama he served as secretary of defense and later as director of the CIA.

Mr. Panetta stated in his lecture that “the nation’s biggest security issue was its inability to deal with the budget.” Although many will interpret his statement as a call to cut the deficit, what he was really criticizing was the Congress’ inability to produce and pass a spending budget that would put some certainty into the ability of the nation to do strategic long term planning.

Like most Washington public servants, Mr. Panetta holds the old-fashioned view that federal budgets should be balanced and the magnitude of deficits is an important metric for the economy. This view is appropriate for households and businesses that have limited financial resources. However, the federal government issues the nation’s currency and is not constrained by financial resources. It has all the financial resources it needs and is constrained only by the nation’s productive resources.

Both political parties are dominated by the false view that the federal budget must be balanced. The only difference is that conservatives think the government has a spending problem and liberals think it is a revenue problem. Both are wrong and it is hurting America’s competitive global advantages.

In the modern world of fiat currency the federal government must focus on real resources (available materials, factories, infrastructure, labor, knowledge) instead of financial resources (money and bonds) in managing the economy. Money is the vehicle that allows the smooth movement of goods and services from sellers to buyers in the economy. The federal government as the sole issuer of the U.S. dollar can issue all the money it needs to move any resources of the nation.

The U.S. and most other nations of the world have used a fiat monetary system since President Nixon defaulted on the gold standard in 1971. Under a gold standard the quantity of money available to the nation is determined by its store of gold, which limits economic growth. Under a fiat system the available money varies with the growth of the economy, and depends on bank loans and federal spending. In the absence of adequate bank loans to make investments in our main-street economy, Congressional budget decisions are responsible for reviving a depressed economy.

The Congressional budget exercise should not be about achieving a balanced federal budget. The budget should be developed to assure that all available resources of the nation are put to good use. There is plenty of work to be done, and we can avoid high unemployment. The federal government can employ all the resources not employed by private industry. If unemployment is high, as it is now, federal deficits are too small.

Many will denounce deficits as causing inflation or adding to a gigantic national debt. They forget to mention that inflation is the result of demand greater than our productive capacity. But, government purchases of either goods or services from labor, which are readily available because of high unemployment, increase total production along with demand, and that benefits businesses. Such purchases are not inflationary.

They also fail to mention that the huge national debt is in reality a huge private asset. The national debt is nothing more than government bonds that individuals, banks, and pension funds hold in their accounts as secure savings instruments.

Mr. Panetta is correct that the nation is weakened when it fails to deal with the budget. But, forcing the federal budget to be balanced either by reducing spending or increasing taxes only hurts our main-street economy by preventing it from growing. Such austerity measures are appropriate only on the rare occasion when the economy is overheated and threatening inflation. A depressed economy, which is what we have today, requires higher spending and lower taxes.

The threat to our future generations is not from a gigantic national debt, which is in reality a gigantic collection of safe and secure savings instruments that will be held by our future generations. The real threat results from the U.S. Congress’ failure to responsibly spend money into circulation to fix our failing bridges, highways, waterways, sanitation systems, public schools, state universities and other public services that we citizens rely on in our daily lives.

Duane Catlett lives in Clancy. He is a retired career Ph.D chemist and materials technology manager. He is a student of Modern Money Theory and the role of government in our economy. Dan Metzger lives in Santa Fe, N.M. He is a retired Ph.D physicist and engineering manager. He is a serious student of Modern Money Theory.

QE is a Tax

By Chris Mayer

May 2 — QE is a tax.

That’s an odd thing to say about the Fed’s bond-buying stimulus program, known as quantitative easing, or QE. But the reality of QE is different than what most people think…

To talk about this, I sought out Warren Mosler, a former hedge fund manager and now trailblazing economist. (I first introduced Mosler to you in your February letter, No. 120. See “How Fiat Money Works.”) So on one Sunday afternoon, with Mosler in Italy and me in Gaithersburg, Md., we chatted on Skype about the Fed and its doings.

Mosler was also a successful banker, and he talks about this stuff with the ease that comes from deep familiarity with the plumbing of the system. The U.S. system, importantly, is one of floating exchange rates and a nonconvertible currency. Meaning the government does not fix the price of the dollar against anything (contra what is done in Hong Kong, where they peg their currency to the dollar). And it is not convertible into anything except itself. (You can’t present your dollars to the Fed and demand gold, for instance.)

With those parameters, we started with a simple question: What would the natural rate of interest be if the government didn’t try to interfere in the interest rate market? (“Natural rate” in this context means the risk-free, nominal rate of interest.)

“In some sense, QE is undoing what the Treasury has done.”

Well, before we can answer that, think about the ways the government interferes in the interest rate market. There are two ways, Mosler points out. The first is that the government pays interest on bank reserves, which are essentially checking accounts held at the Fed. Currently, that rate is 25 basis points, or 0.25%.

The second is to offer “alternative accounts at the Fed called Treasury securities.” These are essentially savings accounts and pay higher interest than the checking accounts (or reserve accounts).

“If we eliminated these things, there would no interest paid on reserves, and there would be no securities,” Mosler says. “So the natural rate of interest would be zero.” Like in Japan for 20 years.

Note this doesn’t mean there would be no interest rates. It means absent these interventions, the market would determine interest rates based on credit risk, etc. But there would be no floor — no risk-free rate, no natural rate — put in place by the government.

“Not that you should do it that way,” Mosler says, “but that’s the way to look at it. The base case is zero. Then the Treasury comes in and offers $17 trillion in securities. And that’s a distortion, to some degree. If the Fed did QE and bought them all back, it would put you back to where you started. In some sense, QE is undoing what the Treasury has done.” When the Fed buys securities, it is as if the Treasury never issued them in the first place.

Or as Mosler puts it in a tidy, eight-page paper (more on that in a bit):

It can be argued that asset pricing under a zero interest rate policy is the “base case” and that any move away from a zero interest rate policy constitutes a (politically implemented) shift from this “base case.”

In other words, the government doesn’t have to pay 3% on a 10-year note, as it does today. It doesn’t have to issue bonds at all. It creates dollar deposits (money) in member bank reserve accounts when it spends. By issuing securities/offering alternative interest-bearing accounts, the government pays a lot of interest to the economy.

“So in that sense,” Mosler says, “issuing securities means paying higher rates than the overnight rate. It is a spending increase and has an inflationary bias by adding net financial assets to the system.”

The mainstream view says that when the government sells Treasury securities, it is taking money out of the system, that it’s a deflationary thing to do and it offsets the inflationary effect of deficit spending. “Not true at all,” Mosler says. “Selling Treasuries does not take money out.” What’s happening is akin to a shuffle between checking accounts and savings accounts.

Let’s turn back to the case of QE, where the Fed buys securities. In this case, the economy loses the interest income from those securities.

“QE takes money out of the economy,” Mosler says, “which is what a tax does.” Hence, as noted above, QE is a tax.

“The whole point of QE is to bring rates down,” Mosler says. “If it does bring rates down, that means the rest of the securities the Treasury sells pay less interest too. So it lowers government interest expense even more. Because the government is a net payer of interest, lower rates mean it pays less interest.”

But does it help the economy? Hard to see how it does. Mosler has an interesting take here. I’ll paraphrase as best I can.

Let’s say people ask why the Fed is buying securities. Well, to help the economy. So now people have to think about whether that policy will work or not. If it’s going to work, that means the Fed’s going to be raising rates, because the economy will be getting stronger. The only time QE will bring rates down is if investors think the policy won’t work. It’s a policy that works through expectations, and it works only if investors think it won’t work.

“It’s a disgrace,” he says.

“On top of that, most investors don’t understand it,” Mosler says. “You’ve got the Chinese reading about how the Fed is printing money. And they go and buy gold. There are knock-on effects all over the world, and portfolios are shifting based on perceptions.”

QE, then, because it costs the private sector interest income and doesn’t add money to the economy, is not inflationary. “The evidence is that it is not inflationary,” Mosler says.

Let’s look at it another way. The bank of Japan has been trying to create inflation for 20 years. The Fed’s been trying to create inflation as hard as it can. The European Central Bank too. “It is not so easy for a central bank to create inflation,” he says, “or you’d think one of these guys would’ve succeeded.

“People act like you have to be careful because one false move on inflation expectations and, bang, you have hyperinflation,” Mosler chuckles. “If you know what that false move is, tell Janet Yellen [the current Fed chief], because she’s trying to find it.”

Though he no longer runs a hedge fund, Mosler is still involved in financial markets. He has a portfolio he runs for himself and for other people. I asked him if he fears interest rates going up.

“It could happen,” he says. “It’s a political decision where rates go.”

And that’s a good place to leave it. Because it brings us back to the beginning. Without the government wading into the interest rate market, the base rate would be zero. And everybody would be working off that. But instead, we have the Fed trying to find monetary nirvana.

As Mosler says, it’s a disgrace.

These are challenging ideas, I know. If you want to read more, look up “The Natural Rate of Interest is Zero,” a tightly reasoned, accessible eight-page paper by Mathew Forstater and Warren Mosler. You can find it free online.

By: Martin Wolf

The giant hole at the heart of our market economies needs to be plugged

Printing counterfeit banknotes is illegal, but creating private money is not. The interdependence between the state and the businesses that can do this is the source of much of the instability of our economies. It could – and should – be terminated.

It is perfectly legal to create private liabilities. He has not yet defined ‘money’ for purposes of this analysis

I explained how this works two weeks ago. Banks create deposits as a byproduct of their lending.

Yes, the loan is the bank’s asset and the deposit the bank’s liability.

In the UK, such deposits make up about 97 per cent of the money supply.

Yes, with ‘money supply’ specifically defined largely as said bank deposits.

Some people object that deposits are not money but only transferable private debts.

Why does it matter how they are labeled? They remain bank deposits in any case.

Yet the public views the banks’ imitation money as electronic cash: a safe source of purchasing power.

OK, so?

Banking is therefore not a normal market activity, because it provides two linked public goods: money and the payments network.

This is highly confused. ‘Public goods’ in any case aren’t ‘normal market activity’. Nor is a ‘payments network’ per se ‘normal market activity’ unless it’s a matter of competing payments networks, etc. And all assets can and do ‘provide’ liabilities.

On one side of banks’ balance sheets lie risky assets; on the other lie liabilities the public thinks safe.

Largely because of federal deposit insurance in the case of the us, for example. Uninsured liabilities of all types carry ‘risk premiums’.

This is why central banks act as lenders of last resort and governments provide deposit insurance and equity injections.

All that matters for public safety of deposits is the deposit insurance. ‘Equity injections’ are for regulatory compliance, and ‘lender of last resort’ is an accounting matter.

It is also why banking is heavily regulated.

With deposit insurance the liability side of banking is not a source of ‘market discipline’ which compels regulation and supervision as a simple point of logic.

Yet credit cycles are still hugely destabilising.

Hugely destabilizing to the real economy only when the govt fails to adjust fiscal policy to sustain aggregate demand.

What is to be done?

How about aggressive fiscal adjustments to sustain aggregate demand as needed?

A minimum response would leave this industry largely as it is but both tighten regulation and insist that a bigger proportion of the balance sheet be financed with equity or credibly loss-absorbing debt. I discussed this approach last week. Higher capital is the recommendation made by Anat Admati of Stanford and Martin Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute in The Bankers’ New Clothes.

Yes, a 100% capital requirement, for example, would effectively limit lending. But, given the rest of today’s institutional structure, that would also dramatically reduce aggregate demand -spending/sales/output/employment, etc.- which is already far too low to sustain anywhere near full employment levels of output.

A maximum response would be to give the state a monopoly on money creation.

Again, ‘money’ as defined by implication above, I’ll presume. The state is already the single supplier/monopolist of that which it demands for payment of taxes.

One of the most important such proposals was in the Chicago Plan, advanced in the 1930s by, among others, a great economist, Irving Fisher.

Yes, a fixed fx/gold standard proposal.

Its core was the requirement for 100 per cent reserves against deposits.

Reserves back then were ‘real’ gold certificates.

The floating fx equiv would be 100% capital requirement.

Fisher argued that this would greatly reduce business cycles,

And greatly reduce aggregate demand with the idea of driving net exports to increase gold/fx reserves, or, alternatively, run larger fiscal deficit which, on the gold standard, put the nation’s gold supply at risk

end bank runs

Yes, banks would only be lending their equity, so there is nothing to ‘run’

and drastically reduce public debt.

If you wanted a vicious deflationary spiral to lower ‘real wages’ and drive net exports

A 2012 study by International Monetary Fund staff suggests this plan could work well.

No comment…

Similar ideas have come from Laurence Kotlikoff of Boston University in Jimmy Stewart is Dead, and Andrew Jackson and Ben Dyson in Modernising Money.

None of which have any kind of grasp on actual monetary operations.

Here is the outline of the latter system.

First, the state, not banks, would create all transactions money, just as it creates cash today.

Today, state spending is a matter of the CB crediting a member bank reserve account, generally for further credit to the person getting the corresponding bank deposit. The member bank has an asset, the funds credited by the CB in its reserve account, and a liability, the deposit of the person who ultimately got the funds.

If the bank depositor wants cash, his bank gets the cash from the CB, and the CB debits the bank’s reserve account. So the person who got paid holds the cash and his bank has no deposit at the CB and the person has no bank deposit.

So in this case the entire ‘money supply’ would consist of dollars spent by the govt. But not yet taxed. That’s called the deficit/national debt. That is, the govt’s deficit would = the (net) ‘money supply’ of the economy, which is exactly the way it is today.

Customers would own the money in transaction accounts,

They already do

and would pay the banks a fee for managing them.

:(

Second, banks could offer investment accounts, which would provide loans. But they could only loan money actually invested by customers.

So anyone who got paid by govt (directly or indirectly) could invest in an account so those same funds could be lent to someone else. Again, by design, this is to limit lending. And with ‘loanable funds’ limited in this way, the interest rate would reflect supply and demand for borrowing those funds, much like and fixed exchange rate regime.

So imagine a car company with a dip in sales and a bit of extra unsold inventory, that has to borrow to finance that inventory. It has to compete with the rest of the economy to borrow a limited amount of available funds (limited by the ‘national debt’). In a general slowdown it means rates will skyrocket to the point where companies are indifferent between paying the going interest rate and/or immediately liquidating inventory. This is called a fixed fx deflationary collapse.

They would be stopped from creating such accounts out of thin air and so would become the intermediaries that many wrongly believe they now are. Holdings in such accounts could not be reassigned as a means of payment. Holders of investment accounts would be vulnerable to losses. Regulators might impose equity requirements and other prudential rules against such accounts.

As above.

Third, the central bank would create new money as needed to promote non-inflationary growth. Decisions on money creation would, as now, be taken by a committee independent of government.

What does ‘create new money’ mean in this context? If they spend it, that’s fiscal. If they lend it, how would that work? In a deflationary collapse there are no ‘credit worthy borrowers’ as they system is in technical default due to ‘unspent income’ issues. Would they somehow simply lend to support a target rate of interest? Which brings us back to what we have today, apart from deciding who to lend to at that rate, the way today’s banks decide who to lend to? And it becomes a matter of ‘public bank’ vs ‘private bank’, but otherwise the same?

Finally, the new money would be injected into the economy in four possible ways: to finance government spending,

That’s deficit spending, as above, and no distinction regards to current policy

in place of taxes or borrowing;

Same as above. For all practical purposes, all govt spending is via crediting a member bank account.

to make direct payments to citizens;

Same thing- net fiscal expenditure

to redeem outstanding debts, public or private;

Same

or to make new loans through banks or other intermediaries.

As above, that’s just a shift from private banking to public banking, and nothing more.

All such mechanisms could (and should) be made as transparent as one might wish.

The transition to a system in which money creation is separated from financial intermediation would be feasible, albeit complex.

No, it’s quite simple actually, as above.

But it would bring huge advantages. It would be possible to increase the money supply without encouraging people to borrow to the hilt.

Deficit spending does that.

It would end “too big to fail” in banking.

That’s just a matter of shareholders losing when things go bad which is already the case.

It would also transfer seignorage – the benefits from creating money – to the public.

That’s just a bunch of inapplicable empty rhetoric with today’s floating fx regimes.

In 2013, for example, sterling M1 (transactions money) was 80 per cent of gross domestic product. If the central bank decided this could grow at 5 per cent a year, the government could run a fiscal deficit of 4 per cent of GDP without borrowing or taxing.

In any case spending in excess of taxing adds to bank reserve accounts, and if govt doesn’t pay interest on those accounts or offer interest bearing alternatives, generally called securities accounts, the consequence is a 0% rate policy. So seems this is a proposal for a permanent zero rate policy, which I support!!! But that doesn’t require any of the above institutional change, just an announcement by the cb that zero rates are permanent.

The right might decide to cut taxes, the left to raise spending. The choice would be political, as it should be.

And exactly as it is today in any case

Opponents will argue that the economy would die for lack of credit.

Not if the deficit spending is allowed to ‘shift’ from private to public.

I was once sympathetic to that argument. But only about 10 per cent of UK bank lending has financed business investment in sectors other than commercial property. We could find other ways of funding this.

Govt deficit spending or net exports are the only two alternatives.

Our financial system is so unstable because the state first allowed it to create almost all the money in the economy

The process is already strictly limited by regulation and supervision

and was then forced to insure it when performing that function.

The liability side of banking isn’t the place for market discipline, hence deposit insurance.

This is a giant hole at the heart of our market economies. It could be closed by separating the provision of money, rightly a function of the state, from the provision of finance, a function of the private sector.

The funds to pay taxes already come only from the state.

The problem is that leadership doesn’t understand monetary operations.

This will not happen now. But remember the possibility. When the next crisis comes – and it surely will – we need to be ready.

Agreed!!!!!

French Prime Minister Manuel Valls Outlines Spending Cuts

(WSJ) French Prime Minister Manuel Valls unveiled some details as to how the government aims to extract €50 billion ($69 billion) in savings between 2015 and 2017.

Almost reads like he knows savings comes from deficit spending!

;)

Mr. Valls indicated for the first time that the government is prepared to take aim at politically sensitive areas of France’s welfare state to achieve the savings, including freezing benefit and pension payments at current levels for the next year. He also said a freeze in the basic pay of civil servants would continue.

Since the price level is ultimately a function of prices paid by govt, this type of thing is a highly disinflationary force.

“I am obliged to tell the truth to French people. Our public spending represents 57% of our national wealth. We can’t live beyond our means,” Mr. Valls said.

Which is true under their current institutional arrangements. So seemes no move to ‘change the rules’

Mr. Valls said the central state would account for €18 billion of the savings; local authorities €11 billion; health care €10 billion; and social security €11 billion.

Draghi says a stronger euro would trigger looser ECB policy (Reuters)

Except by my calculations he has it backwards, as lower rates make a currency like the euro stronger, not weaker, via the interest income channels, etc.

ECB President Mario Draghi said that euro appreciation over the last year was an important factor in bringing euro zone inflation down to its current low levels, accounting for 0.4-0.5 percentage point of decline in the annual rate, which stood at 0.5 percent year-on-year in March. “I have always said that the exchange rate is not a policy target, but it is important for price stability and growth. And now, what has happened over the last few months is that is has become more and more important for price stability,” Draghi said at a news conference. “So the strengthening of the exchange rate would require further monetary policy accommodation.

As above.

If you want policy to remain accommodative as now, a further strengthening of the exchange rate would require further stimulus,” he said.

I agree, except I’d propose leaving rates at 0 fiscal relaxation to the point of domestic full employment, etc.

Furthermore, their policy of depressing domestic demand to drive exports/competitiveness has successfully resulted in growing net exports. However, unless combined with buying fx reserves of the targeted market areas, the euro appreciates until the net exports reverse, regardless of ‘monetary policy.’

When asked about the growth in hourly wages:

Most measures of wage increases are running at very low levels. Wage inflation closer to 3% or 4% would be expected given some measures, such as productivity growth. But right now it is certainly not flashing. An increase in it might signal some tightening or meaningful increase over time. I would say were not seeing that.

It’s well publicized that real wages have been lagging for maybe 40 years, as profits hit an all time high of about 11% of GDP. So as a point of logic the only way wages can stop the slide is if they grow faster than GDP grows, which leads to the ‘where the productivity growth has been going’ discussion, etc. Furthermore, in today’s economy the distribution is largely and necessarily a result of an impossibly ‘complex’, global, institutional structure rather than ‘free market forces’.

Add to that the Fed only has ‘one lever’ which is interest rates, and they all believe that lowering rates is ‘easing’, and that GDP growth promotes wage grow. So it could be that hourly wage growth of 2% that looks like it’s heading to prior highs of around 4% per se might not be all that strong a factor for quite a while in their reaction function?

Lessons from Crises, 1985-2014

Stanley Fischer[1]

It is both an honor and a pleasure to receive this years SIEPR Prize. Let me list the reasons. First, the prize, awarded for lifetime contributions to economic policy, was started by George Shultz. I got my start in serious policy work in 1984-85, as a member of the advisory group on the Israeli economy to George Shultz, then Secretary of State. I learned a great deal from that experience, particularly from Secretary Shultz and from Herb Stein, the senior member of the two-person advisory group (I was the other member). Second, it is an honor to have been selected for this prize by a selection committee consisting of George Shultz, Ken Arrow, Gary Becker, Jim Poterba and John Shoven. Third, it is an honor to receive this prize after the first two prizes, for 2010 and for 2012 respectively, were awarded to Paul Volcker and Marty Feldstein. And fourth, it is a pleasure to receive the award itself.

When John Shoven first spoke to me about the prize, he must have expected that I would speak on the economic issues of the day and I would have been delighted to oblige. However, since then I have been nominated by President Obama but not so far confirmed by the Senate for the position of Vice-Chair of the Federal Reserve Board. Accordingly I shall not speak on current events, but rather on lessons from economic crises I have seen up close during the last three decades and about which I have written in the past starting with the Israeli stabilization of 1985, continuing with the financial crises of the 1990s, during which I was the number two at the IMF, and culminating (I hope) in the Great Recession, which I observed and with which I had to deal as Governor of the Bank of Israel between 2005 and 2013.

This is scheduled to be an after-dinner speech at the end of a fine dinner and after an intensive conference that started at 8 a.m. and ran through 6 p.m. Under the circumstances I shall try to be brief. I shall start with a list of ten lessons from the last twenty years, including the crises of Mexico in 1994-95, Asia in 1997-98, Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999-2000, Argentina in 2000-2001, and the Great Recession. I will conclude with one or two-sentence pieces of advice I have received over the years from people with whom I had the honor of working on economic policy. The last piece of advice is contained in a story from 1985, from a conversation with George Shultz.

I. Ten lessons from the last two decades.[2]

Lesson 1: Fiscal policy also matters macroeconomically. It has always been accepted that fiscal policy, in the sense of the structure of the tax system and the composition of government spending, matters for the behavior of the economy. At times in the past there has been less agreement about whether the macroeconomic aspects of fiscal policy, frequently summarized by the full employment budget deficit, have a significant impact on the level of GDP. As a result of the experience of the last two decades, it is once again accepted that cutting government spending and raising taxes in a recession to reduce the budget deficit is generally recessionary. This was clear from experience in Asia in the 1990s.[3] The same conclusion has been reached following the Great Recession.

Who would have thought?…

At the same time, it needs to be emphasized that there are circumstances in which a fiscal contraction can be expansionary particularly for a country running an unsustainable budget deficit.

Unsustainable?

He doesn’t distinguish between floating and fixed fx policy. At best this applies to fixed fx policy, where fx reserves would be exhausted supporting the peg/conversion. And as a point of logic, with floating fx this can only mean an unsustainable inflation, whatever that means.

More important, small budget deficits and smaller rather than larger national debts are preferable in normal times in part to ensure that it will be possible to run an expansionary fiscal policy should that be needed in a recession.

Again, this applies only to fixed fx regimes where a nation might need fx reserves to support conversion at the peg. With floating fx nominal spending is in no case revenue constrained.

Lesson 2: Reaching the zero interest lower bound is not the end of expansionary monetary policy. The macroeconomics I learned a long time ago, and even the macroeconomics taught in the textbooks of the 1980s and early 1990s, proclaimed that more expansionary monetary policy becomes either impossible or ineffective when the central bank interest rate reaches zero, and the economy finds itself in a liquidity trap. In that situation, it was said, fiscal policy is the only available expansionary tool of macroeconomic policy.

Now the textbooks should say that even with a zero central bank interest rate, there are at least two other available monetary policy tools. The first consists of quantitative easing operations up and down the yield curve, in particular central bank market purchases of longer term assets, with the intention of reducing the longer term interest rates that are more relevant than the shortest term interest rate to investment decisions.

Both are about altering the term structure of rates. How about the lesson that the data seems to indicate the interest income channels matter to the point where the effect is the reverse of what the mainstream believes?

That is, with the govt a net payer of interest, lower rates lower the deficit, reducing income and net financial assets credited to the economy. For example, QE resulted in some $90 billion of annual Fed profits returned to the tsy that otherwise would have been credited to the economy. That, with a positive yield curve, QE functions first as a tax.

The second consists of central bank interventions in particular markets whose operation has become significantly impaired by the crisis. Here one thinks for instance of the Feds intervening in the commercial paper market early in the crisis, through its Commercial Paper Funding Facility, to restore the functioning of that market, an important source of finance to the business sector. In these operations, the central bank operates as market maker of last resort when the operation of a particular market is severely impaired.

The most questionable and subsequently overlooked ‘bailout’- the Fed buying, for example, GE commercial paper when it couldn’t fund itself otherwise, with no ‘terms and conditions’ as were applied to select liquidity provisioning to member banks, AIG, etc. And perhaps worse, it was the failure of the Fed to provide liquidity (not equity, which is another story/lesson) to its banking system on a timely basis (it took months to get it right) that was the immediate cause of the related liquidity issues.

However, and perhaps the most bizarre of what’s called unconventional monetary policy, the Fed did provide unlimited $US liquidity to foreign banking systems with its ‘swap lines’ where were, functionally, unsecured loans to foreign central banks for the further purpose of bringing down Libor settings by lowering the marginal cost of funds to foreign banks that otherwise paid higher rates.

Lesson 3: The critical importance of having a strong and robust financial system. This is a lesson that we all thought we understood especially since the financial crises of the 1990s but whose central importance has been driven home, closer to home, by the Great Recession. The Great Recession was far worse in many of the advanced countries than it was in the leading emerging market countries. This was not what happened in the crises of the 1990s, and it was not a situation that I thought would ever happen. Reinhart and Rogoff in their important book, This Time is Different,[4] document the fact that recessions accompanied by a financial crisis tend to be deeper and longer than those in which the financial system remains operative. The reason is simple: the mechanisms that typically end a recession, among them monetary and fiscal policies, are less effective if households and corporations cannot obtain financing on terms appropriate to the state of the economy.

The lesson should have been that the private sector is necessarily pro cyclical, and that a collapse in aggregate demand that reduces the collateral value of bank assets and reduces the income required to support the credit structure triggers a downward spiral that can only be reversed with counter cyclical fiscal policy.

In the last few years, a great deal of work and effort has been devoted to understanding what went wrong and what needs to be done to maintain a strong and robust financial system. Some of the answers are to be found in the recommendations made by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision and the Financial Stability Board (FSB). In particular, the recommendations relate to tougher and higher capital requirements for banks, a binding liquidity ratio, the use of countercyclical capital buffers, better risk management, more appropriate remuneration schemes, more effective corporate governance, and improved and usable resolution mechanisms of which more shortly. They also include recommendations for dealing with the clearing of derivative transactions, and with the shadow banking system. In the United States, many of these recommendations are included or enabled in the Dodd-Frank Act, and progress has been made on many of them.

Everything except the recognition of the need for immediate and aggressive counter cyclical fiscal policy, assuming you don’t want to wait for the automatic fiscal stabilizers to eventually turn things around.

Instead, what they’ve done with all of the above is mute the credit expansion mechanism, but without muting the ‘demand leakages’/’savings desires’ that cause income to go unspent, and output to go unsold, leaving, for all practical purposes (the export channel isn’t a practical option for the heaving lifting), only increased deficit spending to sustain high levels of output and employment.

Lesson 4: The strategy of going fast on bank restructuring and corporate debt restructuring is much better than regulatory forbearance. Some governments faced with the problem of failed financial institutions in a recession appear to believe that regulatory forbearance giving institutions time to try to restore solvency by rebuilding capital will heal their ills. Because recovery of the economy depends on having a healthy financial system, and recovery of the financial system depends on having a healthy economy, this strategy rarely works.

The ‘problem’ is bank lending to offset the demand leakages when the will to use fiscal policy isn’t there.

And today, it’s hard to make the case that us lending is being constrained by lack of bank capital, with the better case being a lack of credit worthy, qualifying borrowers, and regulatory restrictions- called ‘regulatory overreach’ on some types of lending as well. But again, this largely comes back to the understanding that the private sector is necessarily pro cyclical, with the lesson being an immediate and aggressive tax cut and/or spending increase is the way go.

This lesson was evident during the emerging market crises of the 1990s. The lesson was reinforced during the Great Recession, by the contrast between the response of the U.S. economy and that of the Eurozone economy to the low interest rate policies each implemented. One important reason that the U.S. economy recovered more rapidly than the Eurozone is that the U.S. moved very quickly, using stress tests for diagnosis and the TARP for financing, to restore bank capital levels, whereas banks in the Eurozone are still awaiting the rigorous examination of the value of their assets that needs to be the first step on the road to restoring the health of the banking system.

The lesson remaining unlearned is that with a weaker banking structure the euro zone can implement larger fiscal adjustments- larger tax cuts and/or larger increases in public goods and services.

Lesson 5: It is critical to develop now the tools needed to deal with potential future crises without injecting public funds.

Yes, it seems the value of immediate and aggressive fiscal adjustments remains unlearned.

This problem arose during both the crises of the 1990s and the Great Recession but in different forms. In the international financial crises of the 1990s, as the size of IMF packages grew, the pressure to bail in private sector lenders to countries in trouble mounted both because that would reduce the need for official financing, and because of moral hazard issues. In the 1980s and to a somewhat lesser extent in the 1990s, the bulk of international lending was by the large globally active banks. My successor as First Deputy Managing Director of the IMF, Anne Krueger, who took office in 2001, mounted a major effort to persuade the IMF that is to say, the governments of member countries of the IMF to develop and implement an SDRM (Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism). The SDRM would have set out conditions under which a government could legally restructure its foreign debts, without the restructuring being regarded as a default.

The lesson is that foreign currency debt is to be avoided, and that legal recourse in the case of default should be limited.

Recent efforts to end too big to fail in the aftermath of the Great Recession are driven by similar concerns by the view that we should never again be in a situation in which the public sector has to inject public money into failing financial institutions in order to mitigate a financial crisis. In most cases in which banks have failed, shareholders lost their claims on the banks, but bond holders frequently did not. Based in part on aspects of the Dodd-Frank Act, real progress has been made in putting in place measures to deal with the too big to fail problem. Among them are: the significant increase in capital requirements, especially for SIFIs (Systemically Important Financial Institutions) and the introduction of counter-cyclical capital buffers for banks; the requirement that banks hold a cushion of bail-in-able bonds; and the sophisticated use of stress tests.

The lesson is that the entire capital structure should be explicitly at full risk and priced accordingly.

Just one more observation: whenever the IMF finds something good to say about a countrys economy, it balances the praise with the warning Complacency must be avoided. That is always true about economic policy and about life. In the case of financial sector reforms, there are two main concerns that the statement about significant progress raises: first, in designing a system to deal with crises, one can never know for sure how well the system will work when a crisis situation occurs which means that we will have to keep on subjecting the financial system to tough stress tests and to frequent re-examination of its resiliency; and second, there is the problem of generals who prepare for the last war the financial system and the economy keep evolving, and we need always to be asking ourselves not only about whether we could have done better last time, but whether we will do better next time and one thing is for sure, next time will be different.

And in any case an immediate and aggressive fiscal adjustment can always sustain output and employment. There is no public purpose in letting a financial crisis spill over to the real economy.

Lesson 6: The need for macroprudential supervision. Supervisors in different countries are well aware of the need for macroprudential supervision, where the term involves two elements: first, that the supervision relates to the financial system as a whole, and not just to the soundness of each individual institution; and second, that it involves systemic interactions. The Lehman failure touched off a massive global financial crisis, a reflection of the interconnectedness of the financial system, and a classic example of systemic interactions. Thus we are talking about regulation at a very broad level, and also the need for cooperation among regulators of different aspects of the financial system.

The lesson are that whoever insures the deposits should do the regulation, and that independent fiscal adjustments can be immediately and aggressively employed to sustain output and employment in any economy.

In practice, macroprudential policy has come to mean the deployment of non-monetary and non-traditional instruments of policy to deal with potential problems in financial institutions or a part of the financial system. For instance, in Israel, as in other countries whose financial system survived the Great Recession without serious damage, the low interest rate environment led to uncomfortably rapid rates of increase of housing prices. Rather than raise the interest rate, which would have affected the broader economy, the Bank of Israel in which bank supervision is located undertook measures whose effect was to make mortgages more expensive. These measures are called macroprudential, although their effect is mainly on the housing sector, and not directly on interactions within the financial system. But they nonetheless deserve being called macroprudential, because the real estate sector is often the source of financial crises, and deploying these measures should reduce the probability of a real estate bubble and its subsequent bursting, which would likely have macroeconomic effects.

And real effects- there would have been more houses built. The political decision is the desire for real housing construction.

The need for surveillance of the financial system as a whole has in some countries led to the establishment of a coordinating committee of regulators. In the United States, that group is the FSOC (Financial Stability Oversight Council), which is chaired by the Secretary of the Treasury. In the United Kingdom, a Financial Policy Committee, charged with the responsibility for oversight of the financial system, has been set up and placed in the Bank of England. It operates under the chairmanship of the Governor of the Bank of England, with a structure similar but not identical to the Bank of Englands Monetary Policy Committee.

Lesson 7: The best time to deal with moral hazard is in designing the system, not in the midst of a crisis.

Agreed!

Moral hazard is about the future course of events.

At the start of the Korean crisis at the end of 1997, critics including friends of mine told the IMF that it would be a mistake to enter a program with Korea, since this would increase moral hazard. I was not convinced by their argument, which at its simplest could be expressed as You should force Korea into a greater economic crisis than is necessary, in order to teach them a lesson. The issue is Who is them? It was probably not the 46 million people living in South Korea at the time. It probably was the policy-makers in Korea, and it certainly was the bankers and others who had invested in South Korea. The calculus of adding to the woes of a country already going through a traumatic experience, in order to teach policymakers, bankers and investors a lesson, did not convince the IMF, rightly so to my mind.

Agreed!

Nor did they need an IMF program!

But the question then arises: Can you ever deal with moral hazard? The answer is yes, by building a system that will as far as possible enable policymakers to deal with crises in a way that does not create moral hazard in future crisis situations. That is the goal of financial sector reforms now underway to create mechanisms and institutions that will put an end to too big to fail.

There was no too big to fail moral hazard issue. The US banks did fail when shareholders lost their capital. Failure means the owners lose and are financially punished, and new owners with new capital have a go at it.

Lesson 8: Dont overestimate the benefits of waiting for the situation to clarify.

Early in my term as Governor of the Bank of Israel, when the interest rate decision was made by the Governor alone, I faced a very difficult decision on the interest rate. I told the advisory group with whom I was sitting that my decision was to keep the interest rate unchanged and wait for the next monthly decision, when the situation would have clarified. The then Deputy Governor, Dr. Meir Sokoler, commented: It is never clear next time; it is just unclear in a different way. I cannot help but think of this as the Tolstoy rule, from the first sentence of Anna Karenina, every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.

It is not literally true that all interest rate decisions are equally difficult, but it is true that we tend to underestimate the lags in receiving information and the lags with which policy decisions affect the economy. Those lags led me to try to make decisions as early as possible, even if that meant that there was more uncertainty about the correctness of the decision than would have been appropriate had the lags been absent.

The lesson is to be aggressive with fiscal adjustments when unemployment/the output gap starts to rise as the costs of waiting- massive quantities of lost output and negative externalities, particularly with regard to the lives of those punished by the government allowing aggregate demand to decline- are far higher than, worst case, a period of ‘excess demand’ that can also readily be addressed with fiscal policy.

Lesson 9: Never forget the eternal verities lessons from the IMF. A country that manages itself well in normal times is likely to be better equipped to deal with the consequences of a crisis, and likely to emerge from it at lower cost.

Thus, we should continue to believe in the good housekeeping rules that the IMF has tirelessly promoted. In normal times countries should maintain fiscal discipline and monetary and financial stability. At all times they should take into account the need to follow sustainable growth-promoting macro- and structural policies. And they need to have a decent regard for the welfare of all segments of society.

Yes, at all times they should sustain full employment policy as the real losses from anything less far exceed any other possible benefits.

The list is easy to make. It is more difficult to fill in the details, to decide what policies to

follow in practice. And it may be very difficult to implement such measures, particularly when times are good and when populist pressures are likely to be strong. But a country that does not do so is likely to pay a very high price.

Lesson 10.

In a crisis, central bankers will often find themselves deciding to implement policy actions they never thought they would have to undertake and these are frequently policy actions that they would have preferred not to have to undertake. Hence, a few final words of advice to central bankers (and to others):

Lesson for all bankers:

Proposals for the Banking System, Treasury, Fed, and FDIC

Never say never

II. The Wisdom of My Teachers

:(

Feel free to distribute, thanks.

Over the years, I have found myself remembering and repeating words of advice that I first heard from my teachers, both academics and policymakers. Herewith a selection:

1. Paul Samuelson on econometric models: I would rather have Bob Solow than an econometric model, but Id rather have Bob Solow with an econometric model than Bob Solow without one.

2. Herb Stein: (a) After listening to my long description of what was happening in the Israeli economy in 1985: Yes, but what do we want them to do?”

(b) The difference between a growth rate of 2% and a growth rate of 3% is 50%.

(c) If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.

3. Michel Camdessus (former head of the IMF):

(a) At 7 a.m., in his office, on the morning that the U.S. government turned to the IMF to raise $20 billion by 9:30 a.m: Gentlemen, this is a crisis, and in a crisis you do not panic

(b) When the IMF was under attack from politicians or the media, in response to my asking Michel, what should we do?, his inevitable answer was We must do our job.

(c) His response when I told him (his official title was Managing Director of the IMF) that life would be much easier for all of us if he would only get himself a cell phone: Cell phones are for deputy managing directors.

(d) On delegation: In August, when he was in France and I was acting head of the IMF in Washington, and had called him to explain a particularly knotty problem and ask him for a decision, You have more information than me, you decide.

4. George Shultz: This event happened in May 1985, just before Herb Stein and I were due to leave for Israel to negotiate an economic program which the United States would support with a grant of $1.5 billion. I was a professor at MIT, and living in the Boston area. Herb and I spoke on the phone about the fact that we had no authorization to impose any conditions on the receipt of the money. Herb, who lived in Washington, volunteered to talk to the Secretary of State to ask him for authorization to impose conditions. He called me after his meeting and said that the Secretary of State was not willing to impose any conditions on the aid.

We agreed this was a problem and he said to me, Why dont you try. A meeting was hastily arranged and next morning I arrived at the Secretary of States office, all ready to deliver a convincing speech to him about the necessity of conditionality. He didnt give me a chance to say a word. You want me to impose conditions on Israel? I said yes. He said I wont. I asked why not. He said Because the Congress will give them the money even if they dont carry out the program and I do not make threats that I cannot carry out.

This was convincing, and an extraordinarily important lesson. But it left the negotiating team with a problem. So I said, That is very awkward. Were going to say To stabilize the economy you need to do the following list of things. And they will be asking themselves, and if we dont? Is there anything we can say to them?

The Secretary of State thought for a while and said: You can tell them that if they do not carry out the program, I will be very disappointed.

We used that line repeatedly. The program was carried out and the program succeeded.

Thank you all very much.

[1] Council on Foreign Relations. These remarks were prepared for presentation on receipt of the SIEPR (Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research) Prize at Stanford University on March 14, 2014. The Prize is awarded for lifetime contributions to economic policy. I am grateful to Dinah Walker of the Council on Foreign Relations for her assistance.

[2] I draw here on two papers I wrote based on my experience in the IMF: Ten Tentative Conclusions from the Past Three Years, presented at the annual meeting of the Trilateral Commission in 1999, in Washington, DC; and the Robbins Lectures, The International Financial System: Crises and Reform Several other policy-related papers from that period appear in my book: IMF Essays from a Time of Crisis (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2004). For the period of the Great Recession, I draw on Central bank lessons from the global crisis, which I presented at a conference on Lessons of the Global Crisis at the Bank of Israel in 2011.

[3] This point was made in my 1999 statement Ten Tentative Conclusions referred to above, and has of course received a great deal of focus in analyses of the Great Recession.

[4] Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is Different, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2009.