[Skip to the end]

An economist who matters

by Kyle Wingfield

(Wall Street Journal) Robert Mundell isn’t in the habit of making fruitless policy recommendations, though some take a long time ripening. Nearly four decades passed between his early work on optimal currency areas and the birth of the euro in 1999 – the same year he received the Nobel Prize for economics.

The Euro had nothing to do with the optimal currency area considerations.

Back in America, there’s an election going on. There’s also been a spate of financial problems, not the least of which is a weak dollar. But Mr. Mundell says “the big issue economically . . . is what’s going to happen to taxes.”

Democratic nominee Barack Obama regularly professes disdain for the Bush tax cuts, suggesting that those growth-spurring measures may be scrapped. “If that happens,” Mr. Mundell predicts, “the U.S. will go into a big recession, a nosedive.”

Even if the lost aggregate demand is more than replaced at the same time?

One of the original “supply-side” economists, he has long preached the link between tax rates and economic growth. “It’s a lethal thing to suddenly raise taxes,” he explains. “This would be devastating to the world economy, to the United States,

Even Laffer, the originator of his curve, does not agree with that.

and it would be, I think, political suicide” in a general election.

That may be true, but so far polls don’t show it.

Should taxes instead be cut again, I ask him, to stimulate the sluggish economy? Mr. Mundell replies that he favors a ceiling of 30% on marginal rates (the current top rate is 35%). He recounts how the past century experienced a titanic struggle over whether tax rates are too high or too low: from a 3% income tax in 1913; up to 60% during World War I; down to 25% before Congress and President Herbert Hoover raised taxes back to 60% in 1932 and “sealed the fate of our economy for a long, long time”; all the way up to 92.5% during World War II

When real output more than doubled, even as 7 million of our best workers went into the military.

before falling in three steps, reaching 28% under President Ronald Reagan; and back to nearly 40% under Bill Clinton before George W. Bush lowered them to their current level.

Deficit spending is much more of a driver of aggregate demand than marginal income tax rates.

In light of this fiscal roller coaster, Mr. Mundell says, “the most important thing that could be done with respect to tax rates now is to make the Bush tax cuts permanent. Eliminating that uncertainty would be more important than pushing for a further cut – in the income tax rates, anyway.”

One tax that he would cut, to 25%, is the corporate tax rate. “It could be even lower,” he says, “but I think it would be a big step to lower it to 25% . . . I made that proposal back in the 1970s.”

Very small potatoes from a macro point of view.

A long-haired Mr. Mundell spent that decade not only arguing for the euro, but laying the intellectual groundwork for the Reagan tax-cut revolution. Mr. Mundell says those tax cuts remain “as important to the United States as the creation of the euro was to Europe – a fundamental change.”

The deficit spending of the Regan years was the driver of the expansion- tax cuts and spending increases.

Combined with Paul Volcker’s tight-money policy at the Fed, which Mr. Mundell also championed, supply-side economics killed off stagflation.

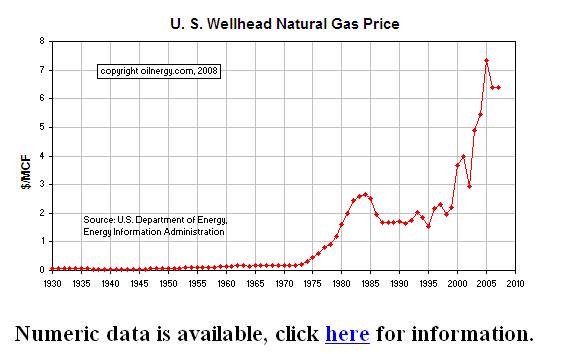

And not the drop in crude prices due to a 15 million barrel per day supply response when natural gas prices were uncapped and utilities switched from oil to gas (and coal, etc.)???

Seems Mundell is pure propaganda.

Or at least it killed it off at the time. With prices again rising as growth slows, some economists are worried that stagflation could be making a comeback. Not Mr. Mundell – not yet.

He draws a comparison with the situation in 1979-1980. Start with the dollar price of oil, which he calls “one of the two most important prices in the world” (the other being the dollar-euro exchange rate, which we’ll get to in a moment).

“If you look at the price level since 1980,” he begins, “oil prices would naturally double by the year 2000. So from $34 a barrel in 1980 to $68 a barrel. And then . . . because the inflation rate’s about 3.5%, it would double again by 2020. So the natural price . . . would be something like $136 in 2020.

So ‘naturally’ doesn’t include inflation???

More to the point, the inflation rate was about 3.5% for 20 years or so with oil prices under $20, so now with oil spiking to $140, inflation should fall to the Fed’s target of maybe 2% due to a modest output gap?

“Now, we [already] got to $130-something, but . . . I really think the price is going to settle down, probably below $100, if not below $90. What I’m saying is we’re not so far off track.”

Guess he forgot the first week of micro that shows how monopolists set price?

As an economist, he should know Saudis are necessarily setting price.

American motorists still shocked by $4-a-gallon gasoline might think we’re rather more off track than Mr. Mundell suggests. Bolstering his case, he immediately moves on to another commodity often invoked to demonstrate inflation: gold.

“The price of gold in 1980 was $850 an ounce. And the price of gold today is about the same. It’s astonishing,” he says. “It’s true, gold did go up” to more than $1,000 an ounce earlier this year, “but the public doesn’t believe that there is inflation. If there was big inflation coming, then you’d see the price of gold going up to $1,500 an ounce very quickly, and that hasn’t happened.”

If they could take Nobel Prizes away, that statement would put him at risk.

In any case, don’t expect to hear Barack Obama or John McCain talk about the weak dollar’s contributions to any problem. “As [journalist] Robert Novak once put it, it’s like cleaning ladies who come in and say ‘I don’t do ironing.’

Good thing he isn’t running with a statement like that.

[Politicians] say, ‘I don’t do exchange rates,'” Mr. Mundell chuckles. “They think they can only lose by talking about exchange rates, because they don’t know enough about it, and it’s hard to predict anyway, for anyone.”

If Mr. Mundell had his way, there wouldn’t be anything for politicians to say about exchange rates. They would be fixed – as they were under the Bretton Woods arrangement after World War II until 1971, when President Nixon took the U.S. off the postwar gold standard and effectively launched the era of floating exchange rates.

“It’s a very poor and a dangerous system,” Mr. Mundell says of the floating regime, “because it creates exaggerated swings in the exchange rate.”

Vs. exaggerated swings in unemployment. Fixed foreign exchange regimes regularly ‘blow up’ with double digit or higher unemployment, negative growth, and actual blood in the streets. They have been abandoned for very good and practical reasons.

Case in point is the dollar-euro rate. From a low of about 82 cents in 2000, Europe’s common currency has risen fairly steadily and has been valued at more than $1.50 since late February, even breaking the $1.60 barrier once.

Without any negative growth, moderate inflation, and, in the Eurozone, declining unemployment.

“What people have to realize is there’s been a fundamental change in the way markets work in the past 20 years,” Mr. Mundell says. “Now, exchange rates are driven not so much by trade but by capital accounts and capital movements, and the huge amount of liquidity that’s sloshing around the world.”

Guaranteed he can’t discuss ‘liquidity sloshing around the world’ beyond that rhetoric.

Central banks world-wide, he notes, are trying to reach an equilibrium between dollars and euros in their $6.5 trillion worth of foreign reserves. Roughly two-thirds of these reserves are kept in dollars now, so they have about $1 trillion left to move into euros.

“If you did a hundred billion dollars” annually, Mr. Mundell points out, “you’d need 10 years to build that up, and that amount of capital movement has a tremendous effect in keeping the euro overvalued. It’s not good for Europe

It does help their real terms of trade, but maybe he doesn’t think that’s ‘good.’

and . . . ultimately it would cause more inflation in the United States.”

It already is, but here he’s denying it.

But this continuing shift doesn’t mean that the dollar’s status as the world’s dominant currency is in danger, at least not in the short run. Countries like Iran may be pushing for the pricing of oil in another currency, “but it wouldn’t happen unless Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states moved in that direction, and I don’t see any way in which they would do this,” Mr. Mundell says.

He also doesn’t ‘see’ that it doesn’t matter what currency anything is ‘priced in’ as it’s just a numeraire. What matters is the currency they ‘save in’ as he mentions when he estimates how they want to hold their reserves and how that matters.

“It would be very damaging to the relations between the United States and the Gulf countries. There’s an implicit defense alliance between those, and that’s what overrides as a top priority.”

Nor is there a macroeconomic argument for demoting the dollar. “Remember, the growth prospects for the United States are probably stronger than that of Europe, because you’ve got continued and substantial population growth in the United States, and zero population growth in Europe,” Mr. Mundell says. “Quite apart from the fact that the U.S. economy is innovating more rapidly, and the population is younger and not getting old as rapidly, so they pick up new technology faster. So I look upon the United States still as the main sparkplug of economic growth in the world.”

He misses his own argument. It’s about what currency non-residents want to ‘save in’ that determines reserve levels and the dollar being a reserve currency.

As for the euro’s overvalued status, he forecasts deflation in Europe,

Negative CPI???

along with a slowdown and an end to its housing boom.

Already happening to some degree.

The answer, he suggests, is for the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank to cooperate in putting a floor and a ceiling on both the euro and the dollar. “You have to grope” to the appropriate range, he maintains, but a good starting point would be to keep the euro between 90 cents and $1.30.

That would mean the ECB buying $ and giving the appearance that the $ is ‘backing’ the Euro as the ECB collects dollar reserves. This is probably unthinkable politically for the Eurozone as they want the Euro to be the world’s reserve currency, not the $.

Even better, in his mind – and now we’re really talking long term – would be to have a global currency. This could take the form of a new money or a dominant existing one to which all others are fixed – probably the dollar. “As Paul Volcker says,” Mr. Mundell relates, “the global economy needs a global currency.”

With no global fiscal authority to regulate aggregate demand? That’s a prescription for economic disaster.

To get there, he proposes holding a new, Bretton Woods-type meeting in 2010 at the Shanghai World’s Fair. Mr. Mundell, who has been spending “a lot of time” in China advising the government, says reviving an international system of fixed exchange rates would be a tremendous help to Beijing as it tries to fend off demands from U.S. and European politicians that it appreciate or float its currency.

Here, he recalls Washington’s similar “bashing” of the Japanese yen in the 1980s, and its ultimately disastrous effects: “Japan got stuck with an overvalued currency for a decade, and suffered from a perpetual deflation in its housing market from 1990 until just a couple of years ago. And China doesn’t want to have the same problem.”

Japan ran/allowed a budget surplus from 1987 to 1992 that wiped out demand and the economy didn’t begin to recover until subsequent deficits got over 7% of GDP.

China isn’t making that mistake.

Another part of his solution is for Asian countries to form their own currency bloc. If they did so, he says, “it’d be comparable in size to the European and the American bloc. And then it would not be so much the question of . . . the U.S. and Europe bashing China” or other rising economies.

He totally misses the roll of aggregate demand.

These three currency blocs, he predicts, would be large enough to weather wide swings in their exchange rates. But the swings would still do economic damage, so “the best thing you could do is to stabilize them, and that’s where the global currency comes in.”

Could it happen? Mr. Mundell allows that three decades may pass, but predicts that like the euro and the Reagan revolution before it, the global currency’s time, too, will come. Any skeptics might want to review the last few decades before betting against him.

I agree the world might do something counter productive like that. Unless there’s something worse they could do that pops up.

[top]