Why Washington’s rescue cannot end the crisis story

by Martin Wolf

Last week’s column on the views of New York University’s Nouriel Roubini (February 20) evoked sharply contrasting responses: optimists argued he was ludicrously pessimistic; pessimists insisted he was ridiculously optimistic. I am closer to the optimists: the analysis suggested a highly plausible worst case scenario, not the single most likely outcome.

Those who believe even Prof Roubini’s scenario too optimistic ignore an inconvenient truth: the financial system is a subsidiary of the state. A creditworthy government can and will mount a rescue. That is both the advantage – and the drawback – of contemporary financial capitalism.

Any government with its own non-convertible currency can readily support nominal domestic aggregate demand at any desired level and, for example, sustain full employment as desired.

The ‘risk’ is ‘inflation’ as currently defined, not solvency.

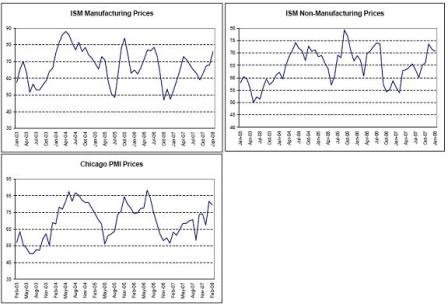

In an introductory chapter to the newest edition of the late Charles Kindleberger’s classic work on financial crises, Robert Aliber of the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business argues that “the years since the early 1970s are unprecedented in terms of the volatility in the prices of commodities, currencies, real estate and stocks, and the frequency and severity of financial crises”*. We are seeing in the US the latest such crisis.

Yes, price volatility has seemingly substituted for output gap volatility.

All these crises are different. But many have shared common features. They begin with capital inflows from foreigners seduced by tales of an economic El Dorado.

With floating fx/non-convertible currency ‘capital inflows’ do not exist in the same sense they do with a gold standard and other fixed fx regimes.

This generates low real interest rates and a widening current account deficit.

The current account deficit is a function of non-resident desires to accumulate your currency. These desires are functions of a lot of other variables.

Non-residents can only increase their net financial assets of foreign currencies by net exports.

This is all an accounting identity.

Domestic borrowing and spending surge, particularly investment in property. Asset prices soar, borrowing increases and the capital inflow grows. Finally, the bubble bursts, capital floods out and the banking system, burdened with mountains of bad debt, implodes.

With variations, this story has been repeated time and again. It has been particularly common in emerging economies. But it is also familiar to those who have followed the US economy in the 2000s.

The US did not get here by that casual path.

Foreign CB accumulation of $US financial assets to support their export industries supported the US trade deficit at ever higher levels.

The budget surpluses of the late 1990s drained exactly that much net financial equity from then non-government sectors (also by identity).

As this financial equity that supports the credit structure was reduced via government budget surpluses, non-government leverage was thereby increased.

This meant increasing levels of private sector debt were necessary to sustain aggregate demand as evidenced by the increasing financial obligations ratio.

Y2K panic buying and credit extended to funding of improbably business plans came to a head with the equity peak and collapse in 2000.

Aggregate demand fell, GDP languished, and the countercyclical tax structure began to reverse the surplus years and equity enhancing government deficits emerged.

Interest rates were cut to 1% with little effect.

The economy turned in Q3 2003 with the retroactive fiscal package that got the budget deficit up to about 8% of GDP for Q3 2003, replenishing non-government net financial assets and fueling the credit boom expansion that followed.

Again, counter cyclical tax policy began bringing the federal deficit down, and that tail wind diminished with time.

Aggregate demand was sustained by increasing growth rates of private sector debt, however it turns out that much of that new debt was coming from lender fraud (subprime borrowers that qualified with falsified credit information).

By mid 2006, the deficit was down to under 2% of GDP (history tells us over long periods of time we need a deficit of maybe 4% of GDP to sustain aggregate demand, due to demand ‘leakages’ such as pension fund contributions, etc.), and the subprime fraud was discovered.

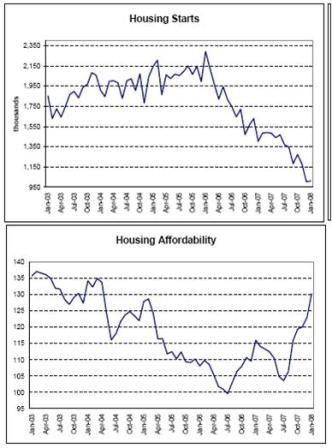

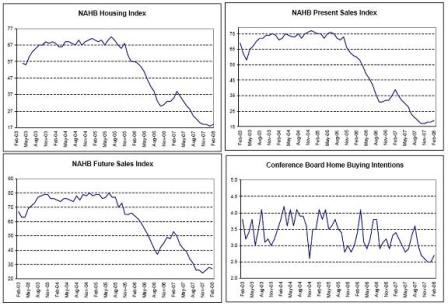

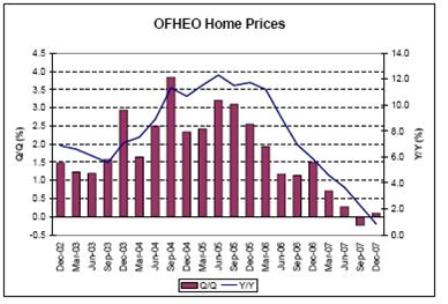

With would-be-subprime borrowers no longer qualifying for home loans, that source of aggregate demand was lost, and housing starts have since been cut in half.

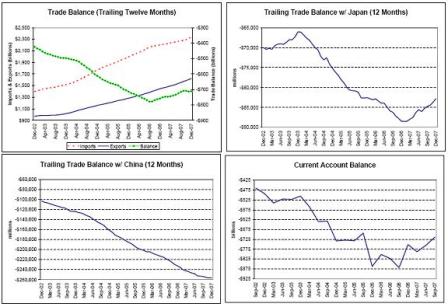

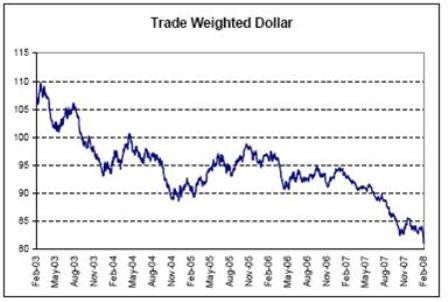

This would have meant negative GDP had not exports picked up the slack as non-residents (mainly CBs) stopped their desire to accumulate $US financial assets. This was Paulson’s work as he began calling any CB that bought $US a currency manipulator and used China as his poster child. Bernanke helped with his apparent ‘inflate your way out of debt/beggar thy neighbor policy’. Bush also helped by giving oil producers ideological reasons not to accumulate $US financial assets.

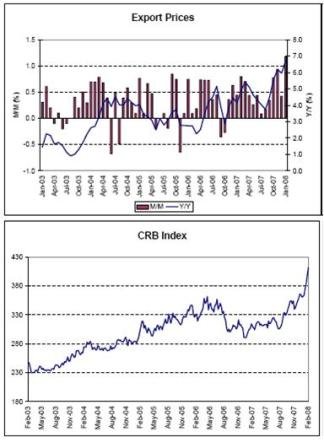

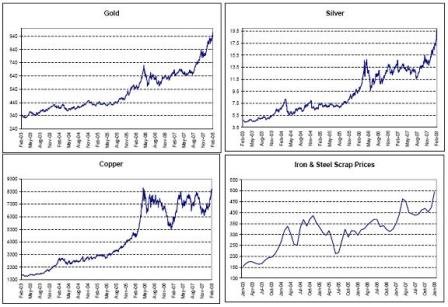

Our own pension funds also helped sustain GDP and push up prices with their policy of allocating to passive commodity strategies as an asset class.

The fiscal package will add about $170 billion to non-government net financial assets, and non-residents reducing their accumulation of $US financial assets via buying US goods and services will also continue to help the US domestic sector replenish its lost financial equity. This will continue until domestic demand recovers, as in all past post World War II cycles.

When bubbles burst, asset prices decline, net worth of non-financial borrowers shrinks and both illiquidity and insolvency emerge in the financial system. Credit growth slows, or even goes negative, and spending, particularly on investment, weakens. Most crisis-hit emerging economies experienced huge recessions and a tidal wave of insolvencies. Indonesia’s gross domestic product fell more than 13 per cent between 1997 and 1998. Sometimes the fiscal cost has been over 40 per cent of GDP (see chart).

Yes, interesting that this time with the boom in resource demand, emerging markets seem to be doing well.

By such standards, the impact on the US will be trivial. At worst, GDP will shrink modestly over several quarters.

Yes, that is the correct way to measure the real cost. Still high, as growth is path dependent, but not catastrophic.

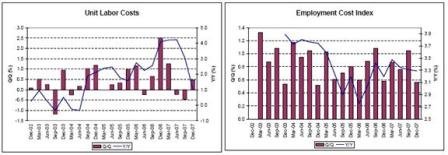

The ability to adjust monetary and fiscal policy insures this. George Magnus of UBS, known for his “Minsky moment”, agrees with Prof Roubini that losses might end up as much as $1,000bn (FT.com, February 25). But it is possible that even this would fall on private investors and sovereign wealth funds.

Those are nominal losses: rearranging of financial assets. The real losses are the lost output/unemployment/etc.

In any case, the business of banks is to borrow short and lend long.

Not US banks – that’s called gap risk, and it’s highly regulated.

Provided the Federal Reserve sets the cost of short-term money below the return on long-term loans, as it has for much of the past two decades, banks can hardly fail to make money.

As above. In fact, with low rates, banks make less on free balances.

If the worst comes to the worst, the government can mount a bail-out similar to the one of the bankrupt savings and loan institutions in the 1980s. The maximum cost would be 7 per cent of GDP.

Again, that’s only a nominal cost, a rearranging of financial assets.

That would raise US public debt to 70 per cent to GDP and would cost the government a mere 0.2 per cent of GDP, in perpetuity.

Whatever that means..

That is a fiscal bagatelle.

Because the US borrows in its own currency,

Spends first, and then borrows to support interest rates, actually

(See Soft Currency Economics.)

it is free of currency mismatches that made the balance-sheet effects of devaluations devastating for emerging economies.

True. ‘External debt’ is not my first choice for any nation.

Devaluation offers, instead, a relatively painless way out of a slowdown: an export surge.

Wrong in the real sense!

Exports are real costs; imports are real benefits. So, a shift as the US has been doing is actually the most costly way to ‘fix things’ in real terms.

And it’s obvious the real standard of living in the US is taking a hit – ‘well anchored’ incomes and higher prices are cutting into real consumption that’s being replaced by real exports/declining real terms of trade, etc.

Between the fourth quarter of 2006 and the fourth quarter of 2007, the improvement in US net exports generated 30 per cent of US growth.

Yes, we work and export the fruits of our labor. In real terms, that’s a negative for our standard of living.

The bottom line, then, is that even if things become as bad as I discussed last week, the US government is able to rescue the financial system and the economy. So what might endanger the US ability to act?

The biggest danger is a loss of US creditworthiness.

Solvency is never an issue. I think he recognizes this but not sure.

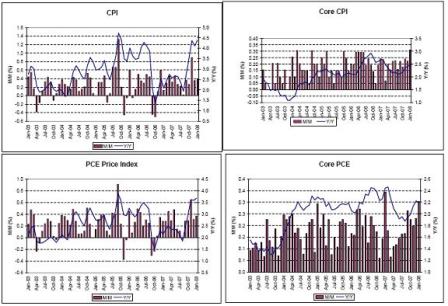

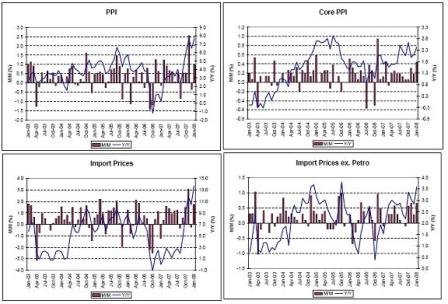

In the case of the US, that would show up as a surge in inflation expectations. But this has not happened. On the contrary, real and nominal interest rates have declined and implied inflation expectations are below 2.5 per cent a year.

I think they are much higher now, but in any case, inflation expectations are a lagging indicator, and in my book cause nothing.

An obvious danger would be a decision by foreigners, particularly foreign governments, to dump their enormous dollar holdings.

The desire to accumulate $US financial assets by foreigners is already falling rapidly, as evidenced by the falling $ and increased US exports. The only way to get rid of $ financial assets is ultimately to ‘spend them’ on US goods, services, and US non-financial assets, which is happening and accelerating. Exports are growing at an emerging market like 13% clip and heading higher.

But this would be self-destructive. Like the money-centre banks, the US itself is much “too big to fail”.

Statements like that make me think he still has some kind of solvency based model in mind.

Yet before readers conclude there is nothing to worry about, after all, they should remember three points.

The first is that the outcome partly depends on how swiftly and energetically the US authorities act. It is still likely that there will be a significant slowdown.

If so, the tax structure will rapidly increase the budget deficit and restore aggregate demand, as in past cycles.

The second is that the global outcome also depends on action in the rest of the world aimed at sustaining domestic demand in response to a US shift in spending relative to income. There is little sign of such action.

True, budget deficits are down all around the world except maybe China and India, especially if you count lending by state supported banks, which is functionally much the same as government deficit spending.

The third point is the one raised by Harvard’s Dani Rodrik and Arvind Subramanian, of the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington DC, (this page, February 26), namely the dysfunctional way capital flows have worked, once again.

I would broaden their point. This is not a crisis of “crony capitalism” in emerging economies, but of sophisticated, rules-governed capitalism in the world’s most advanced economy. The instinct of those responsible will be to mount a rescue and pretend nothing happened. That would be a huge error.

Those who do not learn from history are condemned to repeat it.

And those who keep saying that seem to be the worst violators.

One obvious lesson concerns monetary policy. Central banks must surely pay more attention to asset prices in future. It may be impossible to identify bubbles with confidence in advance. But central bankers will be expected to exercise their judgment, both before and after the fact.

While asset prices are probably for the most part a function of interest rates via present value calculations, my guess is that other more powerful variables are always present.

A more fundamental lesson still concerns the way the financial system works. Outsiders were already aware it was a black box. But they were prepared to assume that those inside it at least knew what was going on. This can hardly be true now. Worse, the institutions that prospered on the upside expect rescue on the downside.

I’d say demand rather than expect. Can’t blame them – whatever it takes – profits often go to the shameless.

They are right to expect this. But this can hardly be a tolerable bargain between financial insiders and wider society. Is such mayhem the best we can expect? If so, how does one sustain broad public support for what appears so one-sided a game?

Watch it and weep.

Yes, the government can rescue the economy. It is now being forced to do so. But that is not the end of this story. It should only be the beginning.

‘should’ ???

* Manias, Panics and Crashes, Palgrave, 2005.

martin.wolf@ft.com

February 27th, 2008 in US economy | Permalink

4 Responses to “Why Washington’s rescue cannot end the crisis story”

Comments

- Kent Janér (guest): Largely, I agree with Martin Wolf’s analysis of what went wrong and what should be done in the future to prevent the by now very familiar pattern of boom and bust in regulated financial systems.There is one aspect that I think merits more attention than it has been given, an aspect that also has some important short term effects – the equity base of the financial system. I think the equity base is currently being mismanaged, and regulators could have some tools to improve the situation.

As everyone knows, there are much more losses in the financial system than have so far been declared. I think close to USD 150 bn has been reported at this stage. That could be compared to for example the G7 comment of 400 bn in mortgage related losses, and 400-1000 bn in total losses probably covering most private sector forecasts. At the same time new risk capital has been raised to the tune of roughly 90 bn USD (ballpark number).

A back of the envelope calculation shows that a large part of the equity of the financial system has been wiped out, much more than has been reported. The market knows, the regulators know and the banks themselves certainly know that even though they are far from bankrupt, they are on average in truth operating at equity/capital adequacy ratios clearly below both legal requirements and sound banking practices.

Currently, the banks are responding by reporting losses little by little, keeping up the appearance of reasonable capitalization. At the same time, they try to reduce their balance sheet, especially from items that carry a high charge to capital. This way they hope (but hope is never a strategy) that time will heal their balance sheet; earnings will over time be able to offset continued writedowns. High vulnerability to negative surprises, but no formal problems with minimum capital adequacy ratios and control of the bank, “only” weak earnings for some time.

That is all very nice and cosy for bank´s directors, but not for the economy in general. If a small part of the banking sector has specific problems and rein in lendig, so be it. That probably has little impact on the rest of the economy. However, if the entire financial sector postpone reported losses and contract their balance sheet, that is another question altogether. The cost to rest of the economy could be very high indeed.

I am less concerned about ‘loanable funds’ with today’s non-convertible currency. I see the issues on the demand side rather than the supply side of funding. Capital ’emerges’ endogenously as a supply side response to potential profits. The reducing lending is largely a function of increased perception of risks.

So, what should be done? Pretending that banks are OK and sweat it out over time is dangerous to economy as a whole, but so is being too harsh on the banks right now.

I actually think there is an answer – the banks should be made to recapitalize quickly and aggressively. Accepting new equity capital would minimize social cost of their current mistakes. There is an obvious practical problem with that, the price at which that capital is available is not necessarily the price at which current shareholders want to be diluted. So, in essence, the banking system continues to push the cost of their mistakes to others by not coming clean on their losses and recapitalize, rather they try to muddle through by not declaring their losses in full and pull in lending to the rest of the economy.

You hit on my initial reaction here. It’s up to the shareholders to supply market discipline via their desire to add equity, and it’s up to the regulators to make sure their funds – the insured deposits (most of the liability side, actually, when push comes to shove) – are protected by adequate capital and regulated bank assets. I think they are doing this, and, if not, the laws are in place and the problem is lax regulation.

I think regulators should be tougher here, banks that clearly are below formal capital adequacy ratios with proper mark to market should be armtwisted to accept new money.

Yes, as above.

I am also looking with dismay on the fact that even some of the weaker banks are still paying dividends to their shareholders – on a global scale I think the financial system has paid out more in dividends since the start of the crisis than they have raised in new capital.

Also, a regulatory matter. Regulators are charged with protecting state funds that insure the bank liabilities.

My proposals have been to not use the liability side of banks for market discipline. Instead, do as the ECB has done and fund all legal bank assets for bank in compliance with capital regulations.

So, a likely situation is that banks with failed business models in the first part of the crisis distribute capital to their owners and somewhat later asks the taxpayer for help…

Kent Janer runs the Nektar hedge fund at Brummer & Partners AB in Sweden Posted by: Kent Janér | February 27th, 2008 at 3:06 pm |